Ms. Kristie Camp is a PhD candidate who has taught English Language Arts for 26 years. Her webinar provides a picture of how to grow environmental literacy in an outdoor classroom.

Flashback to our theme on Financial Literacy! Due to publisher error, Derrick Shepard’s blog was delayed. So, it is now time to hear how Dr. Shepard supports this quote by Jane Bryant Quinn: “No one is born with a mind for personal finances.” Read more about our author at the end of his blog.

Sit with the above quote for a second before moving on. What comes to your mind after you read it? What feelings are elicited? Does the quote speak to you, to the students you are trying to instill a sense of understanding of financial literacy?

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2019) defines “Financial literacy as knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, as well as the skills and attitudes to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts to improve the financial wellbeing of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life.”

The definition is holistic, but it is important to remember that a person’s understanding of financial literacy rests in their knowledge, understanding, attitudes toward financial literacy, and skills to implement a plan that incorporates all three. Now, revisit your thoughts and feelings about the above quote. Did anything change?

There is no denying that individuals need a basic understanding of financial literacy to navigate this capitalist society. Understanding how one’s credit score can impact everything from mortgage rates to credit card rates to the amount you pay for automobile insurance can help save money for the future. As educators, it is incumbent upon us to teach the 3 Rs and relay life skills, including financial literacy, to our students to help them grow into productive and responsible citizens. But how do we do it?

Our students live in a 24-hour, 365-day-a-year social media cycle that never ends. They are bombarded with messages every time they pick up their smartphones, and financial messages (e.g., how to make money) are prominent in the messaging. What I call “salespeople” (and I am being kind) promise riches with little to no effect. Ya, right. Other messages are more “old school” in that they speak to one’s athletic, musical, or artistic abilities to achieve the American Dream. Have you seen some commercials or music videos lately? An example of this is one of Toyota’s commercials for its Tundra Capstone. The actors promote the truck, which is nice and comes in at around $75000 as if it’s a status symbol to achieve to be accepted in the group. As educators, we know group interaction and acceptance are important for one’s development, especially during the pre-adolescent and adolescent years.

So, what messages are students receiving outside of the classroom regarding money?

Reflecting stopping point.

As educators vested in their students’ success, what do you know about them? I bet it’s a lot. You know their likes and dislikes. You know what their home lives are like to a degree. You know them, not as an aggregate reflection of a class roster. No, you know them as individuals with strengths and areas of growth. In knowing and considering this, remember this:

Financial Literacy IS NOT one size fits all.

To the best of your ability, you must consider individual demographics (e.g., racial identity, social class, ethnicity) when constructing an Individual Financial Education Plan (not be confused with an IEP, pun attended). Why is it so important that students’ financial education be individualized as possible? As Frederick Nietzche put it, “‘This-now my way: where is yours?” Thus, I answered those who asked me ‘the way.’ For the way-does not exist.!” As with an IEP, one’s Individual Financial Education Plan (IFEP) needs to be individualized because we all have different backgrounds, values, hopes, and aspirations.

I am not going to leave without some recommendations and resources.

The Psychology of Money (2021) by Morgan Housel is a terrific resource for taking a deeper dive into why we make the decisions we make regarding money. I tweaked his recommendations from the book to fit your students’ age demographics.

- Have students not be too hard on themselves when things go wrong financially.

Setting financial goals is the first step, but as with any goal, things can, and most likely will, go wrong, and mistakes will be made. It is our responsibility to instill a sense of forgiveness in them.

- Focus on wealth and not the ego.

Students are bombarded with messages to spend money. You have to have that new phone. Making saving cool can be (is) hard while living in an instant gratification society. Media does not make it any easier. However, we still need to figure out what makes our students tick and how to circumvent those messages to the best of our ability. Again, we know our students better than some algorithms. 😊

- Time is their friend.

Saving $10 a month does not seem like a lot; however, compound interest is the 8th wonder of the world. Use a time horizon calculator to show them what savings look like today and in the future. There are tons of time horizon calculators out there. Here’s one: https://smartasset.com/investing/investment-calculator

- You can replace money, but you cannot replace time.

Time is as precious as money. You can always get back money, but time is gone. We must impress upon our students to use their time wisely when it comes to finances. I can imagine you already do this in your role as an educator. Just put a twist on it and add the money.

- Be nicer and less flashy.

This gets into social-emotional learning. Housel (2020) states that one “is impressed with possessions as much as you are (p. 209). He argues, instead, that we are looking for respect and admiration from our peers (Housel, 2020). Having kindness and being respectful are other ways to gain respect from our peers.

- Save, baby, save!

Go back to recommendation #3.

- Help your students define what “success” means for them.

I am going to address this recommendation with my counselor educator hat on. Part of being a good counselor is to be open and congruent with clients. As the saying goes, “Clients will only go as deep as you are willing to go with yourself.” With that in mind, we need to remember the core condition of Unconditional Positive Regard (for our students and ourselves) when we teach financial literacy. We need to be Congruent and be who we are with our students when we teach financial literacy, and, finally, we need to show Empathy for those, including ourselves, who are struggling to better themselves but not knowing what they do not know.

- Help students define their “game.”

Financial success looks different for every student. What one considers a success may be an overreach or underreach for the next. There is no way. But, we can help our students reflect, critically think, and plan for a future that fits them.

Finally, I want to leave you with some financial resources that may assist you and your students in gaining a better understanding of personal finance.

The National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE) champions effective financial education. They are the independent, centralizing voice that provides leadership, research, and collaboration to advance financial well-being.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is a U.S. government agency dedicated to ensuring you are treated fairly by banks, lenders, and other financial institutions.

Khan Academy offers practice exercises, instructional videos, and a personalized learning dashboard that empowers learners to study at their own pace in and outside the classroom.

- 15 Financial Literacy Activities for High School Students (PDFs) (moneyprodigy.com)

- https://www.kidsmoney.org/teachers/financial-literacy-activities-high-school/

I hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it for you. The financial literacy journey is complex and ever-changing. But what does not change is our duty as educators to help our students grow and develop into the individuals we know they are capable of.

Dr. Stephanie Lemley develops socio-economic awareness as students experience disciplinary literacy in an agricultural setting. Read more about Dr. Lemley at the end of her blog.

As a literacy teacher educator and a PI or Co-PI on three United States Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA/NIFA) grants for professional development in agricultural literacy, I have been fortunate to work with teachers across Mississippi on infusing agricultural literacy into their classroom instruction. Two of my grants have enabled me to create a summer professional development and then host the teachers on the university campus in the fall and spring for follow-up days. This school year I am working with colleagues from Agricultural Education, Leadership, and Communication, Poultry Science, and Food Science and 28 amazing K-12 teachers from across the state. The teachers’ experiences range from starting their first year of teaching to 25+ years in the classroom. We are currently working with content areas such as special education (e.g., gifted and inclusion classrooms), mathematics, ELA, science, welding, and agriculture. During a four-day, intensive workshop this summer, the teachers learned how to incorporate poultry science and food science content knowledge and lab investigations, literacy instruction, and socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills into their classroom.

This is important because most Americans are agriculturally illiterate (Taylor, 2021, July 7). In fact, in most cases, individuals are three generations removed from the farm, which means more and more people are not aware of where their food comes from (Brandon, 2012, March 30). The American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (2012) has created pillars of ag literacy, one of which is understanding the connections between agriculture and the environment. Hubert et al. (2000) posited that teachers can use agriculture as a topic to teach about the environment and the world around them. This focus on the natural world can also be a great way to infuse socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills into the curriculum as well (Carter, 2016).

Socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills is an “umbrella term used to describe psychological constructs such as personality traits, motivation, or values” (Danner et al., 2021). When teachers teach these skills to their students, they are helping them become efficient workers who know how to build trusting relationships with others, cope with change, serve as leaders, and produce creative solutions to solve problems (Danner et al., 2021). These skills include responsible decision making, self-awareness, self-management, and relationship skills (National University, 2022, Aug. 17). Agricultural topics are the perfect place to teach socio-emotional skills to students because of the diversity of content and emphasis on problem solving. For example, when discussing food choices, students are practicing the socio-emotional skill of responsible decision making; when working in groups to complete labs, students will be practicing the socio-emotional skills of social awareness and relationship skills.

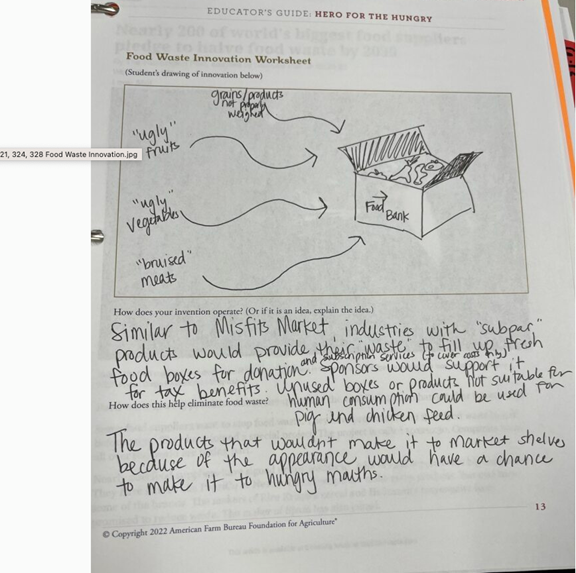

Here’s an example of how teachers who work with me in the four-day workshop investigate the topic of ‘hunger in Mississippi’ through book readings (How Did That Get in My Lunchbox?: The Story of Food by Chris Butterworth, Maddi’s Fridge by Lois Brandt, and Free Lunch by Rex Ogle), online investigations, and proposed solutions to food waste in local communities. We tied the topic of hunger to a variety of Mississippi state science standards.

Table 1. Example Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Science

| Example Science Standards |

| L.K.1A Students will demonstrate an understanding of living and nonliving things. L.K.3A Students will demonstrate an understanding of what animals and plants need to live and grow.L.2.3A Students will demonstrate an understanding of the interdependence of living things and the environment in which they live. L.2.3A.1 Evaluate and communicate findings from informational text or other media to describe how animals change and respond to rapid or slow changes in their environment (fire, pollution, changes in tide, availability of food/water). L.5.3B Students will demonstrate an understanding of a healthy ecosystem with a stable web of life and the roles of living things within a food chain and/or food web, including producers, primary and secondary consumers, and decomposers. L.5.3B.1 Obtain and evaluate scientific information regarding the characteristics of different ecosystems and the organisms they support (e.g., salt and fresh water, deserts, grasslands, forests, rain forests, or polar tundra lands). L.5.3B.2 Develop and use a food chain model to classify organisms as producers, consumers, or decomposers. Trace the energy flow to explain how each group of organisms obtains energy. L.7.3 Students will demonstrate an understanding of the importance that matter cycles between living and nonliving parts of the ecosystem to sustain life on Earth. L.7.3.5 Design solutions for sustaining the health of ecosystems to maintain biodiversity and the resources needed by humans for survival (e.g., water purification, nutrient recycling, prevention of soil erosion, and prevention management of invasive species). |

On the first day of the workshop, teachers investigate ‘hunger’ in their local school district, local community, and the state. First, they searched “hunger in Mississippi” and looked at sites such as Mississippi Food Network (https://www.msfoodnet.org/about-us/hunger/) and Feeding America (https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/mississippi). Then, they searched “hunger in [insert county or city name]. Finally, they looked at hunger in their own school district. One source of data they looked at was from the Mississippi Department of Education (https://www.mdek12.org/sites/default/files/documents/OCN/2023/SFSP/free_and_reduced_data_report_2022-23.pdf). They wrote information that they found on sticky notes and then shared out the information with the rest of the class.

This initial foray into hunger allowed the teachers to learn more about this impactful issue across the state. For many, it reinforced information they already knew about their own community, but it was eye-opening for many to see how big of a problem it is statewide. For example, in looking at the free and reduced lunch data, many were surprised that some of the perceived ‘affluent’ counties in the state still had multiple schools with high percentages of free and reduced lunch. As such, this topic introduced them to a part of environmental and agricultural literacy—food literacy (Siegner, 2019). Food literacy is defined as “the scaffolding that empowers individuals, households, communities, and nations to protect diet quality through change and strengthen dietary resilience over time. It is composed of a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills, and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare, and eat food to meet needs and determine intake” (Vidgen & Gallegos, 2014, p. 54). In addition, this investigation reinforced the SEL skill of social awareness—showing understanding and empathy to others—because it required them to reflect on their own students and how many of them might come to school hungry and need additional sustenance to stay focused during the school day. The second day, the teachers worked in groups to create an innovative way to address food waste in communities. This activity required them to think scientifically and utilize precise science and engineering terminology and design methods to create their solution. We chose this activity because many of the teachers had recently talked about how much food was wasted either at restaurants or at their schools during lunch and how they would like to put some of that food to good use in their community.

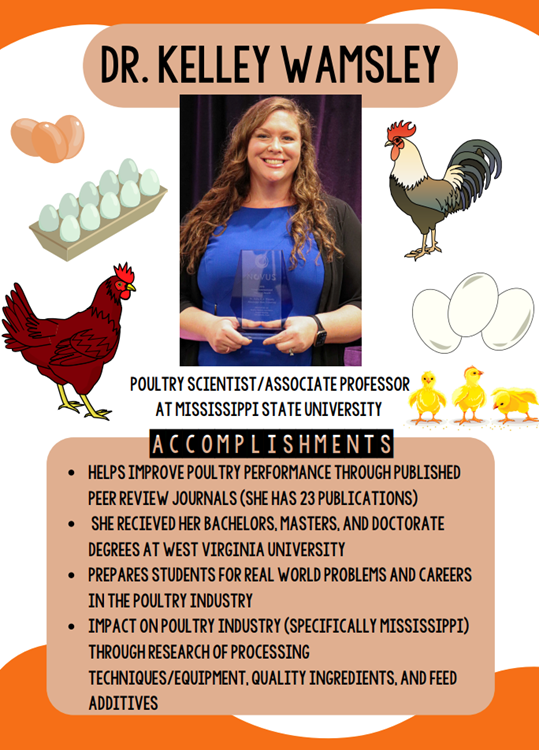

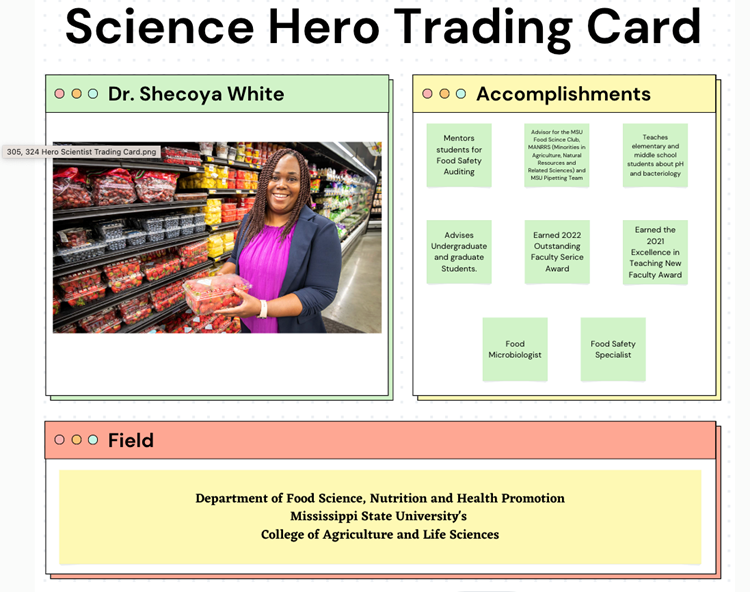

On the third day, the teachers, in groups, created hero scientist cards on a food science or poultry science scientist who has done work that impacts hunger in the state. This activity required the teachers to showcase a scientist who has had a positive impact in improving Mississippi’s environment and its agricultural industry. This activity also required the teachers to not only work on SEL skills such as relationship skills and self-management, but also to use discipline-specific terminology related to the food science or poultry science field when adding information to their trading card.

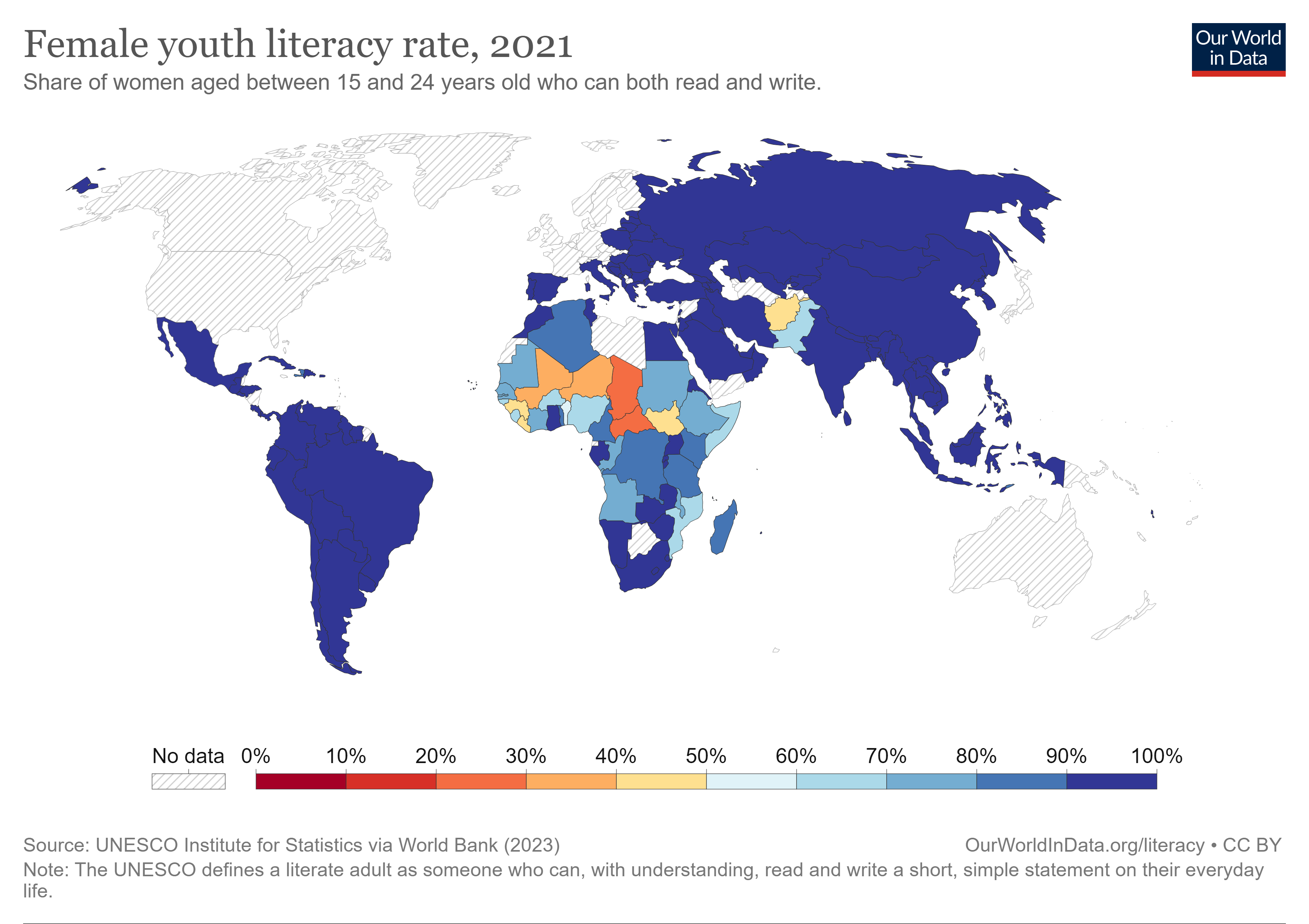

After the summer PD, the teachers returned to their classrooms and implemented lessons that we had done with them in their own teaching. Many used the agriculture texts to teach SEL skills and the food supply. They used the strategies and activities we taught them, and they also shared their new knowledge with their colleagues at their school site or in their district. During the fall follow-up day, the teachers continued to investigate hunger, but this time looked at it not just from a regional and state perspective but also a worldwide perspective. I chose to focus on hunger more broadly this time to show them how they could have their students consider hunger in their own community first (as we did in the summer) but then have them realize that hunger is not just a Mississippi problem—in fact it is a problem in our region, country, and world as well. The lesson and activities I implemented were also tied to state standards in the science, mathematics, social studies, and ELA standards.

Table 2. Example Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards.

| Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Social Studies | Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Science | Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for English/Language Arts |

| 6.8 Examine how humans and the physical environment are impacted by the extraction of resources and by natural hazards 3. Assess the opportunities and constraints for human activities created by the physical environment. | ENV.4 Students will demonstrate an understanding of the interdependence of human sustainability and the environment. ENV.4.3 Enrichment: Research and analyze case studies to determine the impact of human‐related and natural environmental changes on human health and communicate possible solutions to reduce/resolve the dilemma. | RI.6.7 Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue. |

First, they watched a video about the area of Memphis, TN, that is a food desert (see link in resources). The video was then tied into the National Agriculture in the Classroom lesson on ‘Hunger and Malnutrition (see link in resources). In this lesson, students investigate the importance of eating a variety of nutritious foods and explore diets around the world. The teachers were introduced to more health and food science terminology such as nutrient, undernourishment, food bank, staples, accompanying foods, and hunger. They then used the National Geographic website, What the World Eats, and answered the following questions:

- Which country consumes the most calories in a day?

- Which country consumes the fewest calories in a day?

- Which country consumes the most 1) red meat, 2) grain, 3) sugar, and 4) fat?

- Which country consumes the least 1) red meat, 2) grain, 3) sugar, and 4) fat?

After they had worked on this investigation, we discussed what they found across groups. These activities continued reinforcing SEL skills such as social awareness, relationship skills, and self-management as they negotiated group tasks. It also provided them an opportunity to continue to investigate environmental and agricultural literacies specifically food literacy. This is important because part of being agriculturally literacy involves understanding the food system and the importance of plants and animals to our environment. The workshop concluded with the teachers being introduced to two short films from Mississippi State University Films: one of which was on food insecurity, and one of which was on a local school district response to schools shutting down during the COVID-19 pandemic and getting food to the students who relied on school lunch as part of their food sources daily. These videos provided a real-world example of people using socio-emotional skills, such as responsible decision making, compassion, and relationship-building to make a difference in the local community. Further, the teachers learned about ways that community members are stepping up to help end food insecurity in their own backyards through the creation of local farmers markets and other means. This can help further develop their agricultural literacy knowledge because they have a deeper understanding of the food system.

I wanted to share these lessons and resources with my teachers because I wanted to show them how they could help their students become more agriculturally literate with a topic that is relevant to everyone—hunger and food. Over the school year, some teachers have emailed me to share how impactful these agricultural literacy SEL lessons have been for their students, particularly reading the book Free Lunch with their class and then investigating hunger in their community and where food comes from. Others expressed this in their delayed post follow up survey. For example, one teacher wrote that creating trading cards has been the most successful activity with their classes. They noted, “The kids love it and are all 100% into it.” Creating the trading cards on scientists allowed students to showcase their learning in a creative way. Another teacher wrote that participating this year helped them have “more opportunities for students to learn agriculture in different cultures, bringing awareness of food deserts and waste.” The teacher said the students particularly enjoyed exploring the National Geographic website and watching the videos about Memphis and food insecurity in the Mississippi Delta; learning about this topic had them think about what nutritious food was available to them on a regular basis outside of school. Another teacher wrote participating in the professional learning gave her “an enhanced sensitivity to food deprivation within my classroom.” These lessons over the past year opened this teachers’ eyes to hunger in their own students and the teacher has made it a priority to have nutritious snacks available for the students. Two others wrote, “All of the SEL!” for their response. Finally, one additional teacher wrote, “From ACRE 2.0, I’ve already used interactive simulations and hands-on experiments in my class. Next, I plan to add collaborative projects and real-world problem-solving tasks. These activities deepen understanding and build teamwork skills. Additionally, I’ll integrate more tech tools for personalized learning.”

References

American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (2012. Pillars of agricultural literacy. https://www.agfoundation.org/files/PillarsPacket062016.pdf

Brandon, H. (2012, March 30). At what cost the disconnect between agriculture and the public? https://www.farmprogress.com/commentary/at-what-cost-the-disconnect-between-agriculture-and-the-public-

Carter, D. (2016). A nature-based social-emotional approach to supporting young children’s holistic development in classrooms with and without walls: The socio-emotional and environmental education development (SEED) framework. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 9-24.

Danner, D., Lechner, C.M., & Spengler, M. (2021). Editorial: Do we need socio-emotional skills? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-3. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723470.

Hubert, D., Frank, A., & Igo, C. (2000). Environmental and agricultural literacy education. Water, Air, Soil Pollution, 123, 525-532. https;//doi.org/10.1023/A:1005260816483

National University. (2022, August 17). What is social emotional learning (SEL): Why it matters. https://www.nu.edu/blog/social-emotional-learning-sel-why-it-matters-for-educators/

Siegner, A.B. (2019). Growing environmental literacy: On small-scale farms, in the urban agroecosystem, and in school garden classrooms [Doctoral dissertation, University of California Berkeley]. UC Campus Repository. https://escholarship.org/content/qt4p16p53v/qt4p16p53v_noSplash_53f7a6e2917068410defb11335b7ac1b.pdf?t=q6z2hg

Taylor, B. (2021, July 7). Ag illiteracy: What happened, and where do we go from here? https://www.agdaily.com/insights/ag-illiteracy-what-happened-where-to-go/

Vidgen, H.A., & Gallegos, D. (2014). Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite, 76, 50-59. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010

Resources

Judd-Murray, R. (2013). Hunger and malnutrition (grades 3-5). National Agriculture in the Classroom. https://agclassroom.org/matrix/lesson/388/

Mississippi Department of Education. (2023). Mississippi college-and-career readiness standards. https://www.mdek12.org/OAE/college-and-career-readiness-standards

Team, I. W. D. (2024, February 14). The hungriest state. MSU Films. https://www.films.msstate.edu/series/the-hungriest-state

What the world eats. National Geographic. (n.d.). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/what-the-world-eats/

YouTube. (2019, November 20). The food deserts of Memphis: Inside America’s hunger capital | divided cities. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6ZpkhPciaUxs

Funding Statement:

This work is supported by the USDA/NIFA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, AFRI Agricultural Workforce Training Priority Area, award # 2022-08873.

About the Author:

Dr. Stephanie M. Lemley is an Associate Professor of Content-Area Literacy and Disciplinary Literacy Instruction in the elementary education program in the Department of Teacher Education and Leadership in the College of Education at Mississippi State University. She is the recipient of three USDA/NIFA grants on professional development in agriculturally literacy (either as PI or Co-PI) and in the last four years has worked with approximately 150 K-12 teachers across the state, either virtually or through face-to-face instruction, on infusing agricultural literacy into their classroom instruction. She can be contacted at smb748@msstate.edu .

Financial Literacy is Financial Behavior

We welcome Dr. Derrick Shepard to our conversation on Financial Literacy! In this webinar, he empowers teachers to explore financial literacy as a social means of communication, co-constructed through the lens of their other identities. Read more about Dr. Shepard below.

Financial Literacy is Financial Behavior

Dr. Derrick Shepard is an Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee, Martin. His research interests include multiculturalism in counseling, social class awareness, skills related to counselor preparation and pedagogical practices in counselor education and supervision.

Rubrics to Support Writers

Dr. Christina Dobbs follows up her webinar with this blog to challenge instructors to create rubrics that grow writing literacy and result in positive student-teacher interaction. Read more about her at the end of the blog.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I had planned a study of writing instruction at the university level that involved interviews with students and visits to introductory writing classes that would help understand how undergraduates had made the transition from high school to university writing. But fate intervened and doing work to observe in class instructional spaces became complicated as we began to teach and work from home, and so I made a decision to just keep interviewing undergraduates about their experiences. Eighty interviews later, I am so glad to have had the opportunity to talk deeply with a wide range of students about their experience of writing in school across their lives and whether and how they see themselves as writers.

This work, alongside some other work with my colleague Chris Leider from UMass Boston, has caused me to spend time thinking deeply about the feedback we explicitly and implicitly give to students about their writing. As a teacher, I always struggled to give feedback on writing in a timely way that still felt deeply engaged with the work, and students didn’t always use the feedback I gave them to improve their writing, which never felt good. This new work about more effective and culturally sustaining feedback for students has helped me to understand what might have worked better in my own classroom and even in my own experience as a writer myself.

Across the work Chris and I have done with teachers over time and what I learned about feedback from my interviews with undergraduates, I have come to a new approach to feedback. Here are two lessons learned across those projects.

Lesson #1: Even if we didn’t know it, students remember our feedback, especially when they feel it was negative.

In talking with undergraduates about the feedback they received on their writing and times they felt proud of their writing, I was shocked by how much they remembered about feedback they had been given. Students relayed memories from elementary, middle, and high school as well as college, and sometimes they still felt strong emotions associated with those memories.

They described memories when a teacher had made them feel as though their ideas were worth engaging and that they had written something thought-provoking. They also described the positive experience of answering questions about their writing when feedback was given or feeling like their work inspired curiosity from the reader.

They also relayed moments when they got feedback that made them feel like their teachers had not really engaged with their ideas. This included times when they only got feedback on surface conventions or grammar, but it also included times when they just got a ‘good job’ or ‘great work’ too. Somehow this insubstantial positive feedback also made students feel as though they had not written ideas worth engaging.

Most importantly, the writers often described wanting to improve their work, but feeling as though some feedback they received was not helping them to do so. Some even described the feedback as showing them they actually would not be able to improve. They described teachers who made them feel as though they were already supposed to know everything before they took the class and those who clearly conveyed that they could improve.

This has led to a few ideas about giving feedback that I carry forward:

- Asking questions about the content seems to matter to many writers.

- Encouraging writers through feedback at various levels of the work, from the overall idea to the conventions, can support students in viewing their work as substantial.

- Telling students that they can improve, and we will help them to do so explicitly can convey our belief in students’ potential for growth.

Lesson #2: It doesn’t matter what you say to students if your rubric says something else.

The rubrics we use to evaluate student writing often use harsh and deficit-driven language to separate students in particular categories. Rubrics will have category labels such as ‘unsatisfactory,’ ‘below expectations,’ or ‘warning’ to delineate performance, with upper category labels with headings like ‘outstanding’ or ‘excellent.’

Then within categories, the statements to describe various levels of performance will have language such as:

- Writer has little or no control over sentence structure.

- Reasoning is incoherent or unclear.

- The use of language fails to demonstrate skill in responding to the task. (This example is from the ACT rubric.)

The designers of rubrics such as these likely did not think they were harshly commenting on students as writers; in fact, they likely thought they were only commenting on the piece of writing at hand and how well it communicates.

But the personal nature of writing and the ways that writers use feedback and comparison to others to drive their own writing self-efficacy (Pajares, 2003; Pajares & Johnson, 1996) makes it clear that writers likely internalize some of this commentary as about themselves, even if the teacher giving feedback did not mean it as such. Indeed, in my interviews with undergraduate students, they frequently described memorable feedback and harsh rubrics from many years earlier (going back to elementary) as drivers of whether they perceived themselves as writers in college years later.

Chris and I developed a question framework to help guide teachers in redesigning rubrics in ways that still convey critical feedback to students in ways that feel encouraging and supportive. We use these four questions to help teams of teachers we work with to revise rubrics to convey feedback in more supportive and equity-driven ways. The four questions (from Dobbs & Leider, 2021) are as follows:

- Does the rubric’s scale of values for judging responses suggest that students have room to grow?

- Do the tools emphasize development and purpose when it comes to language use?

- Does the rubric feedback connect student language to audience?

- Does the tool explicitly acknowledge that students have agency in choosing which of their language resources to use?

We use these questions not to shift the feedback away from various elements of the writing that we want to give feedback about, but rather to push us to phrase our thinking in a way that treats writers in humane and supportive ways.

So, we use these framing questions to rephrase headings and sentences on rubrics. What might have said ‘unsatisfactory’ before might say ‘still learning,’ ‘room to grow,’ or even ‘focus for next time.’ Where we might have said that ‘reasoning was incoherent,’ we might shift to say that ‘the writer’s reasons supporting their argument were challenging for the reader to understand.’

These sorts of changes convey to students that they can still be working on various elements of their writing, which all students are doing and is the purpose of schooling. They can also convey that writing feedback is not a matter of knowing how to do it ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ but it is rather a matter of whether your communicative purpose was understood by the audience. It also conveys that students made choices about the writing they chose to put forward and that they can continue to improve that writing’s purpose, not just it’s perceived correctness on things like punctuation.

Over time, I’ve learned that giving feedback is meaningful to students in ways I had not always realized, and that making purposeful and specific choices in how to give feedback can make a huge difference in how students are able to take up the feedback we give them. That way, years down the road when they are in college and being interviewed, they will relay memories of feeling supported and confident as writers.

References

Dobbs, C. L. & Leider, C. M. (2021). A framework for writing rubrics to support linguistically diverse students. English Journal, 110(5), 60-68.

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 138-158.

Pajares, F. & Johnson, M. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in the writing of high school students: A path analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 33(2), 163-175.

Financial Literacy Policy Update

Tori Young opens our March them with information that has shaped this addition to South Carolina High School Curriculum. Read more about Tori at the end of the blog.

Scrolling through social media, I often see young adults lamenting about why their teachers never taught them about taxes, credit, or interest rates. These adults feel lost and overwhelmed by the financial responsibility thrust upon them. While financial education may not look the same as it did fifteen years ago with Home Economics and Family and Consumer Science classes being defunded in several states, financial literacy is still integrated into many state standards through Social Studies and Freshman Readiness classes such as Economics or College and Career Readiness (CCR) classes. such as EPF.2.PR: “research and analyze the factors that impact personal income and long-term earning potential,” as an indicator in Economics and “students will be able to demonstrate productivity skills that will aid them in school and the workplace” as an objective in CCR.

Financial literacy is one of the few skills taught in schools that has a direct application to life for each student at the moment of learning it and in the future, regardless of their career goals. Knowing how to manage a budget, keep a healthy credit score, take out and pay off loans, and consider healthy investments are something every American adult has to consider on some scale every day. To understand income and expenses, a bank versus a credit union, and credit and debit are simple terms in financial literacy, but understanding them can greatly impact someone’s financial success. Knowing what options are available and what they mean helps consumers make smart financial decisions for themselves and their families, as well as avoid being taken advantage of by banks, loan companies, and businesses.

Lawmakers understand that when their constituents are financially literate, which means they can make better personal and business-related financial decisions, their states have greater economic success. Because of this, lawmakers over the past few years have begun to find ways to prioritize financial education through the standards of existing courses such as high school Economics and CCR courses that are already funded and required for graduation. Some states are even starting to require Personal Finance as a half-credit course, which teaches students how to balance a budget, plan for future expenses, understand banking and payment options, and choose appropriate loan and credit options for their personal goals. As financial literacy in middle and high school education is becoming a topic for our representatives, what should we know as teachers?

As of December of 2023, only 25 states require at least a half credit of personal finance, with five states and Washington D.C. not including personal finance in their standards (Nex Gen Personal Finance). However, the past two years have seen exponential growth in financial literacy in high school education because more politicians have seen the importance of young people becoming financially literate. In South Carolina, back in 2022, lawmakers passed 1.101 (SDE: Graduation Requirements) to require an additional half credit of Personal Finance for graduation beginning with the current freshman class of 2023-2024 (SC Dept of Ed). To meet this requirement, many high schools in SC now require Business Ed, CCR, or Social Studies teachers to step in to teach the course. Not only do these courses help students as individuals to be financially successful, but they help their communities and states as well when everyone has a better understanding of their finances. While only half of our country is requiring this skill to be taught, it is promising that more states will be joining them in the near future.

If you are wondering how this may apply to you as a middle or high school teacher, it has several impacts both in and out of the classroom! As a high school Economics teacher, I have found many skills from other disciplines necessary for my students to teach them personal finance effectively. We regularly calculate budgets, read data tables, and analyze graphs in class to analyze individual finance goals and overall economic patterns. Many of my students who struggle with personal finance struggle with mathematical and scientific literacy taught in the early years of schooling. For instance, the skills built in middle school science, learning about an X and Y axis, or in Algebra when dividing and working with decimals are crucial for students when they get to Personal Finance. You are building the infrastructure of financial literacy!

Financial Literacy makes up the second standard in the current SC Economics standards for social studies. The motive is that “financial literacy is imperative in making individual economic decisions regarding spending, careers, and setting short- and long-term financial goals. Decision-making and marginal analysis tools are essential in evaluating possible financial options. The ability to make wise choices can impact one’s standard of living and future earning potential” (2019 SSCCR). In order to achieve this goal, Economics teachers rely on a foundation of disciplinary literacy across the general education courses. From ELA, we ask students to research reliable sources and read news articles to find key information about the job market to determine if their career choice is feasible and realistic. From Mathematics, we require the ability to add and subtract to manage expenses and balance a budget as well as read a graph to evaluate the highs and lows of the cost of living. And from Science, we are gathering data from sources and testing different financial choices repeatedly to come to a sound conclusion.

We can all agree the weight of financial responsibility is heavy, for everyone. In turn, when these students graduate and begin their careers, whatever that may be, these students will have the knowledge needed to navigate financial independence. And maybe one day, when they are extremely wealthy, they will remember those of us who helped them get there. 😉

If you want to learn more about personal finance and financial literacy or access free curriculum, resources, and games for students, check out www.ngpf.org. If you are an Economics teacher and your state has implemented personal finance into your standards, check out www.econedlink.org and www.everfi.net for great resources and learning modules!

February’s webinar features Dr. Christina Dobbs, director of the English Education for Equity and Justice program at Boston University.

Click below

Palmetto State Literacy Conference

On February 23, 2024, LiD, 6-12 presented “What is Disciplinary Literacy” during a concurrent session of the PSLA Conference 2024. We invite those who attended to provide your feedback.

Click here: Feedback:

Classroom teacher Wanda Littlejohn shares how she engages striving readers using the Jigsaw Strategy. Read more about Wanda at the end of the blog.

My classroom teaching experience began over 20 years ago in an affluent school district where there were only a few elementary schools, two middle schools, and one high school. All of the schools focused on student academic growth and excellence, and they collaborated well together to ensure the content taught was aligned vertically and horizontally. Most of my students read fluently, were motivated to learn new things, and had similar experiences at home and at school. As a science teacher, I rarely had to provide interventions to gain student interest or to help them read and write like scientists. However, over the years I have learned that my experience as a classroom teacher is vastly different and not all students make it to high school knowing how to read and write fluently. According to the 2023 SC Ready test results, only 53% of eighth grade students either met or exceeded the reading expectations for the state while other subgroups such as pupils who are in poverty, Black, multilingual learners, and with disabilities performed at a rate of 42.3% or less (SCSDE, 2023). Because of these results, it is evident that students entering high school need reading support, and high school teachers need to be equipped with strategies that will assist students in all content areas, specifically in science. In this post, I will share how I utilized the jigsaw strategy as a means to facilitate success for striving readers a biology class.

In the January 4, 2022, issue of EdWeek Madeline Will states: “For the millions of students who struggle to read at grade level, every school day can bring feelings of anxiety, frustration, and shame” (p.1). The highly rigorous curricular standards outlining the knowledge and skills students should have by the end of each science course are designed to prepare students to predict outcomes, create procedures, analyze data, and draw conclusions. If over half of the students entering high school are unable to read at grade level, they are not able to meet the science classroom demands, ultimately leading to students’ feeling frustrated and lost in their science classes. Will (2022) goes on to state “…children who don’t receive appropriate support can fall behind in multiple classes, even though they are capable of intellectually understanding the material” (p. 2). If students are intellectually capable of understanding the material, scaffolds need to be put in place to bring that intellectual understanding out of them. Moreover, those strategies need to assist the striving reader’s comprehension of scientific text and vocabulary.

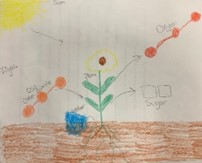

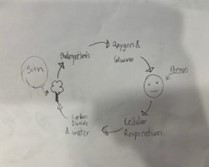

I had the pleasure of providing corrective instruction for several groups of students taking a Biology I course, many of whom were either multilingual learners or were students with a learning disability. During the lesson, we addressed the processes of cell division, cellular respiration, and photosynthesis and their importance to sustaining life. Because these concepts are so abstract, many students find them difficult to grasp. The teacher’s initial testing showed these students needed more time with the content because they were unable to clearly define the concepts or processes which had been taught nor were they able to identify models that represented each concept. It was evident from these data that students needed a way to better comprehend the vocabulary.

Addressing the concern of providing appropriate support for striving readers, I chose to use the jigsaw strategy to support these learners as we revisited the concepts stated above. In John Hattie’s research, the jigsaw strategy has a large effect on student achievement. Hattie proclaims in his book Visible Learning (2009) that self-instruction, organizing, and transforming are valuable tools to get students to be active in their learning and all create a high impact on student growth and achievement. The jigsaw strategy adds student discourse to the lesson and allows students to read, write, speak, and listen within a cooperative setting.

During the lesson, the students were assigned one of the four concepts (photosynthesis, cellular respiration, macromolecules, cell division). The students were given 20 minutes to read articles and listen to videos about their assigned topic. Each student was given a graphic organizer that supported their reading and listening and contained questions they had to answer during their individual research time to ensure they were obtaining the right information about their concepts. After their research phase was complete, the students were given 30 minutes to work in expert groups with other students who had the same concept so they could synthesize and organize their information. The students also had to create a model representing their concept and produce talking points they could use to explain their concept to others. It was imperative for me to conference with each group during the expert phase to ensure they were on the right track and they had accurate descriptions. The final step in the process was to jigsaw the students so each group contained an expert on each concept. During this phase, the students shared their models, while other students filled out a graphic organizer capturing the new information learned. As the jigsaw ended, one student indicated she really felt better about the concepts and she learned so much in the smaller group setting. At the close of the lesson, the students took a short assessment again on each concept.

In Biology, the standards require students to create models to illustrate the processes of both cellular respiration and photosynthesis. The figures above show some of the students’ interpretations of those process after completing the jigsaw activity. It was evident from the figures above that the students had a general understanding of both processes. Figure 2 shows an even deeper understanding that both processes depend on each other and produce a continuous cycle.

In closing, striving readers, according to Will (2022), need a supportive classroom environment where they are welcomed to be risk takers and to have a growth mindset. During a jigsaw activity, there are a lot of moving parts and directions. The advice I would share is to be prepared to redirect students, repeat instructions, and visit each individual during each phase to ensure the students feel supported. Allowing students to research and read individually first gives them an opportunity to make meaning of things before they have to make meaning with a peer. Becoming an expert with a peer allows striving readers to reread and repeat information a second time, which enhances comprehension. I found the jigsaw strategy increased student knowledge of the concepts, gave them the confidence they needed to engage in discussion with their peers, and gave them the ability to complete the models shown in Figures 1 and 2. To learn more about the jigsaw strategy, click here.

January’s webinar features Dr. Ian O’Byrne, an associate professor of literacy education in the Teacher Education Department of the College of Charleston in South Carolina. He reminds us of the positive effect of open dialogue in the classroom when introducing new and controversial instructional tools such as artificial intelligence.

Click here to access the recording.

We welcome Ian O’Byrne as we open our blog and webinar theme: Artificial Intelligence. Please read more about Ian at the end of the blog.

Educators are currently struggling with a significant decision: Should AI be integrated into the writing process? Some worry that it could impede students’ writing skills. This leads to an important question: Have American schools ever been successful in teaching writing? When was writing education at its best? Where is it now? As educators, how can we strike the right balance?

There is no easy answer to these questions. The history of writing education in America is long and complex, and there have been many different approaches to teaching writing over the years. Schools now stand at a crossroads as AI-powered writing tools gain popularity. These technologies promise to enhance instruction and feedback but also raise concerns about over-reliance. To make sense of this balance, let’s first look at what exactly AI is.

What is Generative AI?

The intelligence of computers or software, as opposed to the intellect of people or animals, is known as artificial intelligence (AI). It is a branch of computer science that creates and investigates intelligent machines. Uses of artificial intelligence in the form of an agent, bot, or tool are generally labeled as AI. In the last year, we’ve seen an influx of AI in our lives as ChatGPT exploded on the scene. A far better way to view these tools is to refer to them as Generative AI and not simply as AI or ChatGPT.

Generative AI refers to advanced artificial intelligence systems that can generate new content on their own rather than just responding to user prompts. Models like GPT-3 (ChatGPT) can write entire essays, stories, and code after being trained on vast datasets. This means they may soon be capable of assisting students and teachers with writing tasks like brainstorming ideas, translating rough drafts into more polished work, answering content questions, and even providing feedback.

However, generative AI also raises challenges. Teachers will need to focus on developing original thinking skills rather than knowledge recall, and concerns around plagiarism, creativity, and voice must be addressed. When used judiciously, generative writing tools could enhance instruction and revision. But ultimately, writing education should emphasize the uniquely human aspects of imagination, analysis, and persuasive communication that AI cannot replicate.

What about writing instruction?

The history of writing education in America is a mixed bag. Some of the earliest writing instruction in America took place in one-room schoolhouses, where students were taught the basics of grammar and spelling. Teaching pupils to write included teaching them how to form letters, spell words, and have readable, if not exquisite, handwriting. Writing instruction in American schools began in the late 1800s as colleges started requiring admissions essays. This mostly focused on preparing an elite group of males with a formulaic, five-paragraph structure that developed basic literacy but limited creativity.

Students were required to master the five-paragraph essay, but this method sometimes stifled originality and expression. While it did instill basic writing skills, it may not have nurtured a deep love for writing. Some shifts came in the 1960s and 1970s as the process approach emerged, emphasizing planning, drafting, revising, etc. The National Writing Project (NWP) raised awareness about the ways that writing changes throughout a person’s life, the impact of a range of school and non-school experiences on writing, and the interactions between writing in school and these lived experiences.

Throughout the 20th century, writing instruction continued to follow a rigid, formulaic approach, emphasizing grammar and structure over creativity and critical thinking. Some of this focus on the importance of grammar and mechanics in writing instruction was due in part to the rise of standardized testing, which required students to demonstrate their mastery of these skills. Students were inundated with topic sentences, transitional phrases, and conclusion restatements in the omnipresent five-paragraph essay. Although this method guaranteed a basic level of literacy, creativity and enthusiasm were frequently sacrificed.

In recent years, the tide seems to have turned in favor of more innovation, voice, and freedom of expression. There has been a growing movement to move away from traditional grammar-based approaches to writing instruction and to focus more on helping students develop their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Current best practices involve process-based instruction tailored to students’ needs and interests. Assignments also incorporate more authentic, real-world writing purposes and audiences.

Yet, with this varied history in the focus, goals, and implementation of writing instruction, the teaching of writing has not changed in many schools. Debates continue around balancing process approaches with quality outcomes. Standardized writing tests have been criticized for over-emphasizing grammar at the expense of actual writing skills. Researching writing development, including spelling patterns and the connections between writing, speaking, and reading, is a constant challenge. Other ongoing issues include managing teachers’ heavy workloads, integrating technology for composition and collaboration, and closing achievement gaps for minority students. Simultaneously, some educators find it difficult to strike a balance between grammar and real-world communication possibilities.

Writing Education and Generative AI

Generative AI tools hold great promise, but they also pose risks. Over-scaffolded writing assignments might fail to teach core composition skills. Targeted AI feedback could improve self-editing and reworking while maintaining the humanity of audience awareness and personal narrative. Students can receive immediate, personalized feedback thanks to technologies like AI co-writers, grammar and style checks, and predictive text. Students could become overly dependent on AI recommendations rather than developing their own voice and style. Essay scoring algorithms even mimic the evaluation procedure. Schools should prioritize balancing rather than seeing innovation as a substitute for efficient practice.

As educators and researchers, we need to better understand the appropriate role for writing technologies. How can AI augmentation best complement time-tested instructional methods? Which specific skills should remain the focus for teachers and students? Even with the help of intelligent recommendation systems, collaborative discourse and knowledge might still be developed through writing workshops and reading circles. Both tradition and technology have their place.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to writing instruction, and the best approach for a particular student will depend on their individual needs. It is important to note that writing is a skill that takes time and practice to develop. Students will not become good writers overnight. However, with effective instruction, all students can learn to write well. There are some key principles that we can use to help guide future explorations of writing instruction and AI. These principles include:

- A focus on the writing process as opposed to product, from prewriting to revision

- Opportunities for students to write for a variety of purposes and audiences

- Feedback from teachers, peers, and other agents

- Numerous, varied chances for students to hone their writing abilities

As leaders in literacy, we have the chance to mentor the upcoming generation of authors. When writing instruction veered too much in the direction of either freedom or structure, it went awry. We can provide kids with the best of both worlds by ethically incorporating AI as a tool for improved results. Teaching the craft, generating ideas, finding one’s voice, and fostering a lifelong love of writing continue to be our guiding values. Technology can support this objective if used wisely. We can find the ideal equilibrium if we act carefully and wisely.

Christy Howard returns with additional thoughts through the eyes of a literacy educator who works with preservice and in-service teachers as they navigate the changing expectations of education. Read more about Christy at the end of her blog.

Through my work as a literacy educator, I have the opportunity to work with preservice and in-service teachers as they navigate the changing expectations of education. I also work with school support staff, administrators and district-level curriculum leaders. Through this work I have recently been engaged in many conversations around curriculum materials and text selection for classrooms. Educators want to know how to engage students in the learning process, and how to help them in their journey to becoming critical consumers of texts — especially in a world where they are bombarded with so much information. Many secondary teachers recognize the need to look beyond the textbook for classroom materials, often acknowledging content area textbooks fail to provide all the information needed to support student learning. Many of them also acknowledge textbooks provide incomplete stories. My response to these educators as I nod in agreement is, “Let’s take a look at the role of counternarratives in your materials and text selection process.”

What are counternarratives?

There are many definitions of counternarratives. Here I would like to share the definition from Tricia Ebarvia’s new book, Get Free. She shares:

“A counternarrative is a story that stands in contrast to and challenges the values, beliefs and an established dominant narrative. Often counternarratives do this by focusing on the perspectives that are missing, marginalized, or actively erased from the dominant narrative” (Ebarvia, 2023, p.3).

This definition stands out to me because of the discussion of erasure. When I think about my conversations with educators and their stories of how some of them are dealing with curriculum mandates and banned books in their districts, this is an example of how perspectives are actively erased from the dominant narrative. Curriculum mandates and book bans often minimize access to the ideas, experiences and histories of marginalized groups. This is a clear reason why we need to provide space for multiple perspectives, allowing students to engage with both dominant narratives and counternarratives.

Why are counternarratives important?

Stories that only show the dominant perspective can be harmful. Students need exposure to multiple perspectives. These perspectives are not always readily available in neighborhoods and families. Tatum (2017) reminds us, Many of us grow up in neighborhoods where we had limited opportunities to interact with people different from our own families… Consequently, most of the early information we receive about “others”– people racially, religiously, or socioeconomically different from ourselves–does not come as a result of firsthand experience. The second hand information we receive has often been distorted, shaped by cultural stereotypes, and left incomplete (p. 84).

This incomplete information can lead to harmful actions. For example, incomplete, distorted information shaped by cultural stereotypes has led to physical and emotional harm against people in this country. We have seen this highlighted in news stories about hate crimes against marginalized groups, that in many cases have led to death. These incomplete stories and distorted stereotypes can be addressed through counternarratives in our classrooms, and if we believe dominant narratives can be harmful, it is easy to believe that perhaps counternarratives can be healing.

Counternarratives can also help us disrupt deficit perspectives and harmful narratives about people and places. For so long in the publishing world, we saw so few books written by and about the lives and experiences of people of color. This has been well documented by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (2018). With this approach to publishing, the lives, experiences, and voices of marginalized people have been silenced. Tatum (2017) describes an experience where a preservice English teacher commented that she had never learned about any Black authors in her English courses and was concerned she would have difficulty teaching them if she had not learned about them in her schooling. A classmate commented, “It’s not my fault that Blacks don’t write books” (p. 85). This narrative is harmful, inaccurate, and is rooted in a deficit perspective. We must provide access to books for students that serve as counternarratives to this mindset, showing that we indeed have successful, amazing, authors across marginalized groups writing award-winning stories and creating award-winning film, art, poetry, music and dance. These counternarratives can show our students they, too, can be successful, amazing creators if they so choose to embrace that identity.

Counternarratives in Classrooms

There are many learning experiences you can provide for students to engage with counternarratives. I believe it’s important for students to read counternarratives. I also think it’s important for them to have opportunities to write counternarratives as well. Christensen (2017) asserts, “In writing about themselves, students learn to praise their beauty that the world overlooks or cannot see” (p. 82). Writing experiences through this lens allow students to write against false or inaccurate narratives, take ownership of their writing and show their beauty to the world. Here I want to share some opportunities for both reading and writing with you.

Children’s Books as Counternarratives

We know that children are often exposed to negative dominant perspectives through children’s stories, cartoons, and movies, where they have seen inaccurate representations of Indigenous People, as women portrayed as needing to be rescued, and People of Color, as lazy or villains. As educators, we have the opportunity to disrupt these narratives by using well-chosen, multi-perspective texts in our classrooms as counternarratives. At the bottom of this post, I have listed picture books, middle grade books, and young adult books that can be used as counternarratives. These are all beautiful stories, several of them focusing on love, joy, and community, while also speaking back to the dominant perspectives of marginalized people.

As we consider using such books in our classrooms, there are so many resources that can guide us in choosing texts, such as Diversifying Your Classroom Book Collections? Avoid these 7 Pitfalls. In addition, Ebarvia (2023) provides some questions to guide our thinking as well:

- Can this text provide meaningful insight to students about identities with which they are unfamiliar?

- In what ways can this text help to develop a positive social identity for my students?

- How can this text challenge incomplete or harmful dominant narratives about different identities?

- Does this writer treat their subject with complexity and nuance and avoid stereotypes?

- What does this text not do or include that I will have to supplement with another text? What counternarratives will my students need after this text?

I hope through these resources, you find some helpful texts to meet the needs of your students and engage them in exploring counternarratives in your classrooms.

Visual Autobiographies

Visual autobiographies are an opportunity for students to engage in creating counternarratives. Students can generate multimodal projects that include items such as photos, drawings, poems, songs, and videos. This type of assignment is open for students in a way that they are able to choose what they want to present and how they want to present it. They are able to share their identity, culture, history, beauty, and brilliance. They begin by exploring the dominant narratives that might be told about them, parts of their identities or their communities. They, then, consider how they can create visual representations as counternarratives to these dominant narratives.

Talking Back

Talking Back is an activity Christenson (2017) shares where she asks students to “criticize commercially produced images about the way they should look, sound, or act” (p. 82) and to speak back to these perspectives through poetry. In her example, she uses the poem, “what the mirror said” by Lucille Clifton. I have also used Maya Angelou’s Still I Rise poem as a mentor text. Additionally, I have created a poem as a mentor text for this assignment so students can see my thinking in this process as well. As an educator, what would you like to “talk back” to? What texts could you use with your students as representations of “talking back?”

Reflections of…

I believe in self-reflection. It is an important piece of all of my instructional practices. When I consider what it means to include counternarratives in my classroom, these are the questions I am asking myself. I encourage you to join me in reflection as you consider integrating counternarratives into your classrooms.

- What is the role dominant narratives have played in my life?

- What is my role in promoting the dominant narrative in classroom spaces? How have I believed or accepted deficit dominant narratives?

- How can I challenge the negative perceptions in dominant narratives?

- How do I use narratives to help students construct new understandings of the world?

- Whose experiences and voices are centered in my classroom?

- Whose experiences and voices are marginalized?

- Whose voices are missing? What does this mean? Why does this matter?

- How can I continue to provide space for my students to “talk back?”

Children’s Books and Professional Resources

Picture books

We Are Still Here: Native American Truths Everyone Should Know by Traci Sorell

Something Beautiful by Sharon Denni Wyeth

I Am Every Good Thing by Derrick Barnes

We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom

My Papi Has a Motorcycle by Isabel Quintero

Ada Twist, Scientist by Andrea Beaty

Middle Grade books

Mascot by Charles Watters and Traci Sorell

Some Places More Than Others by Renee Watson

Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis and Traci Sorell

Harbor Me by Jacqueline Woodson

Swim Team by Johnnie Christmas

Young Adult books

Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo

The Silence that Binds Us by Joanna Ho

The 57 Bus by Dashka Slater

Professional Resources

Christensen, L. (2017). Reading, writing, and rising up: Teaching about social justice and the power of the written word. (2nd ed.) Rethinking Schools.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. New York, NY: Scholastic.

References

Christensen, L. (2017). Reading, writing, and rising up: Teaching about social justice and the power of the written word. (2nd ed.) Rethinking Schools.

Cooperative Children’s Book Center. (2018). Publishing statistics on children’s books about people of color and First/Native nations and by people of color and First/Native nations: Authors and illustrators. Madison, WI: Cooperative Children’s Book Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved from https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/literature-resources/ccbc-diversity-statistics/books-by-and-or-about-poc-2018/

DeHart, J., & Staff, L. for J. (n.d.). Countering the narrative. Learning for Justice.

Ebarvia, T. (2024). Get free: Anti-bias literacy instruction for stronger readers, writers, and thinkers. Corwin.

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Tatum, B. D. (2017). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?: And other conversations about race. New York: Basic Books

This webinar features Dr. Christy Howard, Associate Professor in the Department of Literacy Studies, English, Education, and History Education at East Carolina University. She encourages us to be mindful advocates against inaccurate stories, images, and stereotypes about marginalized people.

Click Here to access.

This week we welcome Heather Waymouth and one of her students, Hery Castro as they share the positive effects of rethinking the relationship between disciplinary literacy and equity, expertise, and inclusive education. Read more about Heather and Hery at the end of the blog

I (Heather) came into the field of disciplinary literacy as an excited doctoral student who finally saw a way that my certifications in science and literacy could make sense together. I’d spent years thinking about science as a science teacher and literacy as a literacy teacher, and never the two should mix. That I could now teach students to read science like a scientist and history like a historian felt like putting on a comfortable, old sweater.

Yet, just as my old, comfortable sweater has some holes, so, too, does disciplinary literacy. Heller (2011) and Collin (2014) encourage educators to question what counts as a discipline and if our intent really is to mold students into “little experts.” Saying that we are apprenticing students into the literacy practices of disciplinary experts should cause us to examine who counts as an expert.

That question didn’t meaningfully exist for me until I watched the movie Dark Waters (Haynes, 2019). At the film’s core is a farmer, Wilbur Tennant, seeking to sue DuPont over environmental contamination. He’s reached out to the company several times, they’ve conducted a study of his land and their nearby disposal area, and DuPont’s scientists have claimed there’s nothing wrong. Yet, Tennant has gathered his own data. When his lawyer visits the farm, there’s a poignant scene in which Tennant pulls deformed cow organs wrapped in tinfoil from his freezer, deformed hooves stored in a jar, and a video of himself conducting his own necropsy. However, because Tennant is “just a farmer,” his lived experience and expertise aren’t initially seen as “expert” enough for the law firm to justify taking on his case.

I began to rethink my devotion to disciplinary literacy. Was our focus on a narrow definition of experts and expertise helping to build and maintain the world in which Wilbur Tennant’s decades of intimate knowledge didn’t count? Rather than seek an answer from literacy scholars, I dove into science education research. After all, the newly crafted Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) were intended to promote equitable learning opportunities for ALL students (Lee, Miller & Januszyk, 2015).

In science, I found a conceptualization of literacy that gave me hope for a more inclusive disciplinary literacy. The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine published a report on Science Literacy which defined it across three levels: individual, community, and society (2016). Here, literacy wasn’t a form of property able to be possessed by some folks and not others. Sure, individuals’ mastery of reading, writing, and oral discourse is a necessary consideration of literacy within this model, but it isn’t the end goal. Considering how communities – especially those historically denied access to quality science education – engage in literacy as collective praxis (Roth & Lee, 2002) by bringing their diverse voices, experiences, and literacies together – provided me with a vision for disciplinary instruction which could introduce experts’ literacies and value other forms of literacy and expertise as equally valid.

Then I found Windschitl, Thompson, and Braaten’s (2018) Ambitious Science Teaching. My heart sang – here was a framework that balanced attention to equity and rigor. Not only that, it established students’ collective sensemaking as the objective of science learning. Throughout my dissertation, I observed a group of middle school science teachers using Ambitious Science Teaching to breathe life into the NGSS and had the pleasure of hearing, in their words, how this type of teaching was creating space for all students to engage in sensemaking. While even in their expert teaching, opportunities existed for a closer consideration of equity as foundational rather than supplemental to science learning, I knew I had found my soapbox to stand upon.

Now that I work full-time preparing pre-service teachers, I do everything I can to further the possibilities for equity and inclusion in disciplinary literacy. I have taken up equitable sensemaking (Calabrese Barton & Tan, 2019) as the foundation of my undergraduate class on literacy in the content areas. Throughout the semester, preservice teachers work in small groups to craft a unit plan in a content area other than ELA: science, math, engineering or social studies. We adopt the ambitious science teaching framework (Windschitl, Thompson, & Braaten, 2018), understanding that while this framework was designed for science, it can be applied to any discipline. Preservice teacher teams identify an inquiry question ripe for exploration from multiple viewpoints and for incorporation of social justice and equity, such as “Why do we get sick?” Then, they map an explanation of that phenomenon, incorporating multiple viewpoints and opportunities for students to engage with new ideas, rather than be taught (told) those ideas. As my desire is for authentic learning to drive the bus, I don’t introduce standards until after the ideas mapping process has begun. Students map content area standards first and subsequently “engineer” (Moje, 2015) opportunities for literacy development within their unfolding storyline (Reiser et al., 2021).

Considering equity as foundational is often a new concept for my preservice teachers, given that most are white and from middle class backgrounds. We spend several classes learning what it might look like to incorporate perspectives other than our own early in the planning process. The works of three scholars are particularly helpful to us. While students are developing their unit’s question, we listen to Dr. Danny Morales Doyle’s interview with Abolition Science in which he discussed using social justice science issues, like pollution from a local factory, to ground high school chemistry instruction. Several days into unit planning, students use the twelve questions Dr. Gholdy Muhammad outlined in her AMLE blog post to (re)consider the cultural and historical relevance of their unit. To illustrate what an equitable sensemaking activity that draws upon diverse voices might look like, I conduct a fishbowl discussion in which each student embodies a chapter of Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s (2013) Braiding Sweetgrass, using three guiding questions: What counts as knowledge/expertise? Whose expertise matters? How do we use the knowledge we are gaining from this text to impact our teaching?

The units my students are ultimately able to build astound me. I’ve seen a math unit on how to affordably feed various sized groups, a social studies unit on why we haven’t yet had a woman elected as president, and all sorts of other units incorporating joyful learning, literacy in service to disciplinary learning, incorporations of diverse viewpoints, and opportunities for students’ identities and experiences to inform ongoing learning. But, as I heard on Reading Rainbow as a child of the 90’s, “You don’t have to take my word for it.” Hery Castro is one of my students currently engaging in planning for equitable sensemaking. I’ll let him tell you what it’s like:

Including equitable sensemaking in my unit plan caused me to reshape my thinking, and put critical literacy first, alongside relatable science phenomena. Although there was some slight confusion on what exactly Dr. Waymouth was looking for, I loved working on my assignment. As a person of color who has experienced difficulties with teachers understanding where I’m coming from, I’ve always known that I wanted more perspectives like mine included in school. Being told that it’s not only possible, but necessary to include them in this science unit (a subject area I don’t intend to teach), was affirming.