This webinar features Beth Shaver and provides resources for collecting Social Studies resources from multiple perspectives. Click here to access.

This webinar features Beth Shaver and provides resources for collecting Social Studies resources from multiple perspectives. Click here to access.

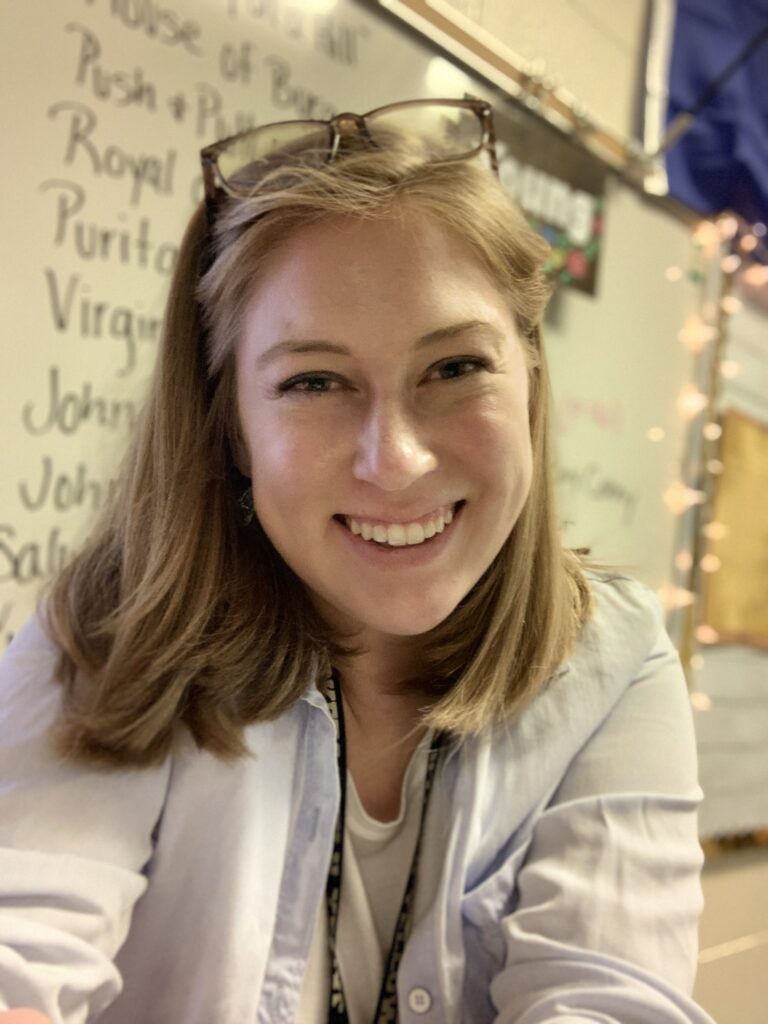

This blog is written by Tori Young and shows us how to scaffold written essays resulting in a video essay. Read more about Tori at the bottom of her post.

Have you ever caught yourself in the never-ending rabbit hole of online video essays? Conspiracy theories, movie plot analyses, theme park history and so many more topics are explained in a thorough manner with research and analysis weaving together ideas and backgrounds you never would have put together. Even if you have not stumbled into this online phenomenon, I can assure you that your students have. Whether hour long YouTube deep-dives, or short TikTok synopsis series, students are being presented with researched information about a wide range of topics even if they do not recognize it. After noticing this for myself, I asked “why aren’t more essays like this?”

Research papers and argumentative essays are the primary form of essay writing used in my history classroom. I want my students to know how to be informed citizens and communicate their ideas and beliefs in a way that is grounded in historical truth and facts. I typically scaffold this process throughout the year using activities based on the content. Typically, I start out with an exit ticket asking students to pick a side on a tough topic (no in between!) and tell me why they chose their stance. Nothing formal just to get them to practice how to take a stance. Slowly I will make them add facts from a document we read in class to back up their positions and eventually start teaching the research process by having them look for reliable sources of their own to support their side. Eventually, all that information can be used to organize and create a well-written paper for social studies.

The broad goals of this process are to teach students how to make informed decisions and communicate their ideas effectively. While a traditional essay is an excellent way to practice those skills, many teachers like me have seen the difficulties for students that come with that ultimate step of writing the paper. For many students, the formal language or length of the writing assignment can be daunting to approach, causing them to shut down before trying. But we look at them confused; they have already practically written the paper with their summaries and research. Why can’t they just fill in the gaps with just a few sentences?

I found myself asking these questions every year. When I asked my students to verbalize their answers, I got great insight and connections to the content from them. They know this content, in fact many of them get passionate about it when it is time for them to argue. As I pondered this, I concluded that most of my students will only share their research and findings about topics verbally in their futures. Why am I not adding a verbal layer of assessment to this process?

This is where the wonderful world of video essays came into play for me and my classes. A video essay takes on the same structure as an essay but uses visual aids and commentary to present the information. Just like a good historical essay, it begins with background information on the topic and a clear thesis. It is then followed by key points that are supported by examples. And lastly, the video concludes with the creator’s main idea and the topic’s historical impact. Video essays help students practice research skills, organizing ideas and examples, but instead of writing, they are practicing presentation skills!

An example of this in my high school US History classes is during our unit on the Antebellum era. There are a lot of names of important people during this period; abolitionists, women’s rights activists, and politicians. I let my students pick from a list of key figures to research to share their life story. I give loose parameters on the assignment, asking students to provide the background of the person’s life, their contributions to Antebellum America, and their lasting impact on the United States. Some students may need more guidance, so it may be helpful to provide examples of information you are looking for such as their birthplace, career, and writings to name a few possibilities. I then ask students to record a two-minute video using WeVideo or Screencastify to present their findings using media to support their discussion.

I have seen my quietest students speak without hesitation in these videos, presenting on topics with great care and speaking skills. The key is that I do not show them in front of the class. Once the fear of being judged by their peers is taken away, students become comfortable with the process. They also begin to get creative with their media. Many will create a PowerPoint to display and follow along with for their video. However, I have seen animations, skits, and eulogies come out of this assignment as students begin to find their creativity with this medium.

Students are still practicing all the skills I need them to learn for my goals, but by incorporating video essays I have seen higher levels of engagement with historical content. This is not meant to take away from the importance of formal writing. While not all our students will go on to university and academia, they will still need to write important emails and apply for jobs. Formal writing is an important skill, but if you also notice students needing an extra step in scaffolding the writing process in social studies then consider video essays. Students will even surprise themselves with how much they know!

Images courtesy of Pexels

This blog is written by Lesley Roessing suggesting that a variety of texts can be used to teach historical events still impacting the world today. Read more about Lesley at the bottom of her post.

No historical event may be as unique and complicated to discuss and teach as the events of September 11, 2001, the day terrorists crashed planes into, and destroyed, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. At the time of this event, no child in our present K-12 educational system was yet born, but, in most cases, their parents and educators would have been old enough to have some knowledge of, and even personal experience with, these events, making this a very difficult historic event for many to teach. However, with the devastation and impact of these events on our past, present, and future and as ingrained a part of history these events are, they need to be discussed and understood as much as possible.

An effective way to learn about these events is through story. Powerful novels have been written about this tragedy, for all age levels and, fascinatingly, each presents a different perspective of the events. Some take place during September 11, some following the events, some a few years later or many years later, and a few include two timelines. Many take place from the perspectives of multiple characters.

On September 11, 2021, YA Wednesday posted my guest-blog “Novels, Memoirs, Graphics, and Picture Books to Commemorate September 11th.” In this blog, I interviewed authors and reviewed and recommended 24 texts and six picture books.

Since then, I have read two additional texts:

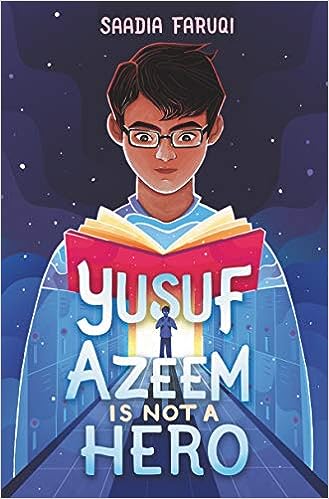

Yusuf Azeem is Not a Hero by Saadia Faruqi

“Suspicion of those unlike us is common human behavior. We don’t trust who we don’t know. But yes, 9/11 was terrible, and it really fueled the fire of hatred in this country.” (184-5)

Sixth grader Yusuf Azeem was born in Texas and is an American; his mother was also born in America and his father was a Pakistani immigrant who runs the popular A to Z Dollar Store in town (and a somewhat a local hero after capturing an intruder threatening his store and customers). The family is Muslim, but, understandably, Yusuf is shocked when sixth grade begins with threatening notes in his locker. When one says, “Go home,” he is hurt and confused. Frey, Texas is his home. Surely the notes are meant for someone else.

This is a novel that may benefit from some background on the events of September 11, 2001, since the action takes places in 2021 but, read individually, Ausuf’s uncle’s journal helps to fill in information. The importance of this particular novel is that it demonstrates that, for some of our citizens and students, “Twenty years. So much time. But things haven’t really changed at all.” (48) One of the major events in the story—when a little computer in his backpack beeped and, instead of questioning him and investigating, Ausuf is thrown in jail for twelve hours—is based on a real event from 2015 where Ahmed Mohamed, a Muslim 14-year-old, was arrested at his high school because of a disassembled digital clock he brought to school to show his teachers [https://www.cnn.com/2015/09/16/us/texas-student-ahmed-muslim-clock-bomb].

It is vital that our children learn about 9/11 because, as Yusuf’s mamoo says, “History informs our present and affects our future.” (81)

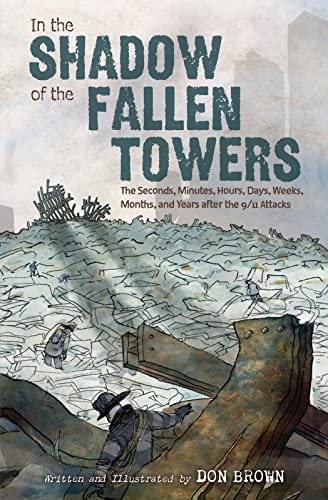

In the Shadows of the Fallen Towers by Don Brown

Don Brown’s graphic novel recounts events following the 9/11 attacks on the Towers and the Pentagon from the moment of the “jetliner slamming into the North Tower of the World Trade Center” to the one-year anniversary ceremonies at the Pentagon, in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, and at Ground Zero. It also covers the fighting of U.S. troops in Afghanistan and the capture and interrogation of prisoners from an al-Qaeda hideout in Pakistan.

The drawings allow readers to bear witness to the heroism of the first responders, firefighters, and police as they move from rescue to recovery over the ten months following the attacks and learn the stories of some of the survivors they saved. It is the story of the nameless “strangers [who] help[ed] one another, carrying the injured, offering water to the thirsty, and comforting the weeping.” (23)

We learn and view details that we may have not known, such as “Bullets start to fly when the flames and heat set off ammunition from fallen police officers’ firearms,” (11) the “Pentagon workers [who] plunge[d] into the smoke-filled building to restore water pressure made feeble by pipes broken in the attack,” (36) and former military who donned their old uniforms and “bluff[ed their way] past the roadblocks” to “sneak onto the Pile” to help. (50, 52)

For more mature readers this book adds to the story of 9/11 in a more “graphic” way.

I have taught a unit on NINE ELEVEN through book clubs in multiple schools from grades 5 through 9 in both ELA and Social Studies classes. Children and adolescents have felt comfortable these sensitive and challenging concepts and examining these troubling events and some of the ensuing difficulties, prejudices, and bullying, through the eyes of characters who are around their ages, some readers sharing personal stories in their small collaborative groups. I am thankful for the authors who have allowed our children to experience these events in a safe and compassionate way. I have presented these novels and strategies and lessons for reading through book clubs at local workshops and national conferences. I included my 9/11 Book Club unit as a chapter in TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher’s Guide To Book Clubs Across The Curriculum.

Condensed and reproduced with permission from https://www.literacywithlesley.com/blog posted on September 2, 2023.

Follow her website, created to support educators—teachers, librarians, and parents, at https://www.literacywithlesley.com/

This post is written by Miriam Necastro. Read more about Miriam at the bottom of this post.

They say you can’t go home again. However, in the case of myself and some of my colleagues, we did by returning for round two at Brookfield Middle School; this time as teachers. At the beginning of the previous school year, our principal had set a goal for us to conduct more cross-curricular collaborations. When we were turned loose for common planning time with our grade-level teachers, we began brainstorming what we could integrate seamlessly across the curriculum divide. My colleague Brad, who teaches 7th grade World History, is also an alum of Brookfield. We started to reminisce about the different cross-curricular projects we completed during middle school. We both agreed that it was as if most of our classes back then were involved in these instructional projects. The other element we remembered was the excitement–our teachers were excited, which made us excited.

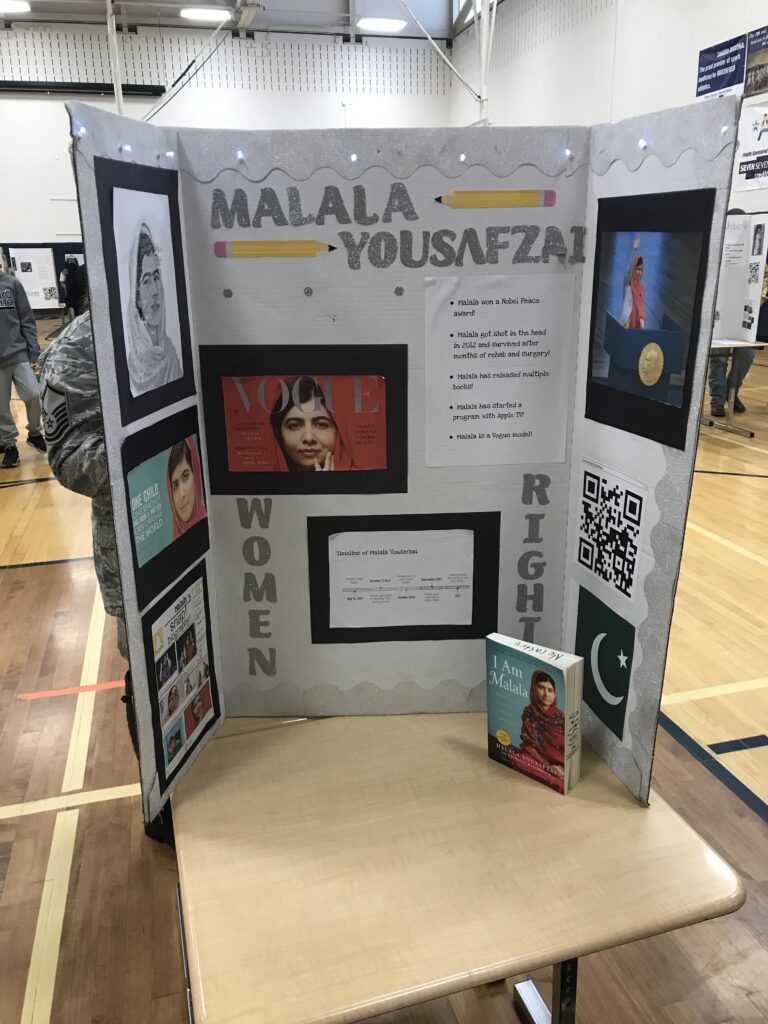

The project in question was known as the “Millennium Project.” At this time, during the early 2000s, A&E Biography released the program “100 Most Influential People of the Millennium.” In our World History class, our teacher wrote each of those individuals on slips of paper, and during class, we drew a name out of a cup. The name of the influential person we drew was the person we would be researching during classes, writing an informational essay, first-person biographical speech, creating a visual display, and portraying this person during the Night at the Museum presentation. What if we brought this project back to life after a seventeen-year hiatus?

We started by creating a dual Google Classroom page where we sectioned off different topics for all the project materials, examples, and assignment drop boxes. He covered the history assignments while I did the Language Arts ones. For example, areas of historical research would be covered by history, while ELA would cover the biographical essay. Based on the event date that was scheduled on the school calendar, we then collaborated on due dates for essential project assignments, agreeing that these would be flexible, if need be, once the unit got underway. Since the students had never completed a large project of this nature, covering two of their core classes, we knew this would be a learning experience for everyone. The fun part came first– having the students select the influential person they would be portraying for the project. The list of influential people ranged from Gandhi to Diana, Princess of Wales to Jane Goodall, Tomoe Gozen, George Washington, Jackie Robinson, Neils Bohr, Dolly Madison, and others.

The best collaboration tool we utilized was Google Classroom. Creating a joint classroom page specifically for this project assisted us in making sure that all students had the same information and materials in one central location. For example, research database websites were organized in their separate section, and my colleague and I would add links if we found a new site that would benefit student research. From an ELA and World History standpoint, we emphasized the importance of credible resources for research, especially when in seventh grade, Wikipedia is so convenient. Our students knew the ‘Research Resources’ section of Google Classroom as their one-stop shop. In an effort to not only conserve paper but also lessen the chances of lost materials, everything was digital. Students printed out their visual presentation text elements when constructing their museum board. As with Google Classroom, we could see student progress on the different parts and pieces of the project, so we could differentiate our instruction in our respective classrooms.

We know students always like to ask the question, “when am I going to use this outside of class?” We felt this project was the perfect opportunity to answer that question and put it to practice. Even though this was considered a history project at first look, the majority of the project was rooted in ELA. Without the Language Arts/writing skills, the students would not have been able to complete the project. The biographical essay that the students completed for their influential person aligned with the Ohio State Test Informative Writing Rubric, and used the research they completed in history class. In both classes, we expressed the importance of not just copying and pasting information from their research sources into their essay; they must use their personal voice. In doing so, not only did it save them from plagiarism, but it also proved to us that they understood the information. They read the information, processed it, decided how it fit into the boundaries of the project, then, put it in their own words. Historical research plus writing and grammar skills combined in these areas of the project: historical research outline, biographical essay, visual display title, biographical timeline, key facts, word cloud, and fake social media page. ELA standards also include goals for speaking and listening. Students fulfilled this standard by using points from their biographical speech to write a speech from the perspective of their historical person to deliver during the “Night at the Museum” event when someone came up to their station.

The culminating event took place during school hours, where our seventh-grade students dressed as their historical person, stationed in front of the visual display they created, celebrating and sharing their knowledge acquired in both history and ELA over the last months. This project proved that lines between curricula don’t have to be so definite. If we combine our areas of expertise as teachers, we can maximize student learning.

Miriam Necastro has 6 years teaching experience and is the 7th grade ELA & Reading teacher at Brookfield Middle School; Brookfield, Ohio. She is currently pursuing an M.Ed in Literacy from Clemson University.

Photo by Skye Studios on Unsplash

By: Julia López-Robertson, University of South Carolina and Rocio Herron, Jackson Creek Elementary School

Last fall I taught a Family Dynamics course and was searching for a way to engage my undergraduate students in meaningful experiences with children and families; the course carries a community service component that is left up to the instructor to design and implement. I sought to involve my students in experiences that would help them develop strategies for authentic family and community engagement that they could later draw upon when they became classroom teachers.

I am very fortunate to be able to spend time in a local Pre-K classroom with a teacher, Rocio Herron, who willingly shares her students and families with me. Rocio has taught at Jackson Creek Elementary School since the school opened three years ago; the majority of the school population is African American (73%), followed by Latino students (13%), and 100% of the students receive free/reduced lunch.

Rocio and I have a history; she was my youngest son’s Pre-K teacher a few years ago (he is now 15). Rocio and I share similar views on teaching and learning and family engagement; we believe that children have a right to their language; children must be actively engaged in their learning; teachers must learn about their children lives outside of school in order to better teach them; and that trusting relationships with families are the cornerstone of teaching.

Family Heritage Project

I spend Friday mornings in Rocio’s classroom engaging the children in bilingual (Spanish/English) read alouds, songs, dances, and games. One Friday I mentioned to Rocio that I was teaching a course with a community service component and wondered if she had any ideas for my class. I explained the time commitment and my goals for the project and she excitedly exclaimed that she had a Family Heritage Project she was looking to do that would involve all three Pre-K classrooms.

The purpose for the Pre-K Family Heritage project was to get to know the children and their families by engaging them in a project about their family. Rocio explained that she also wanted the families to know that they all had things to be proud of and to contribute to the school and society in general; too often our immigrant families and families of color are made to feel insignificant and that they have nothing to offer our schools or their children. Through the project, the families would investigate their heritage, family, and culture and uncover for themselves the tools they possess that can be used for helping their children learn; i.e. language, sewing, gardening. I wanted my students to view the families as contributors of knowledge and see them through an asset-based lens where their funds of knowledge, their community-based ways of knowing (Moll, Amanti, Neff, González, 1992) are recognized as valuable instruments for school learning.

The Family Heritage Project spanned a few weeks in the fall semester. Families were asked to come to school on three evenings; my students and I participated in all activities that took place over the three visits. The first evening was spent getting to know each other; Rocio engaged the families in a read aloud followed by a discussion, families sang songs that the children did in school, families played school games with the children and we all got to know each other. We expanded the view of ‘family heritage’ to include things that you do together as a family because we wanted to be inclusive of all families. Rocio asked them to think about things that they did together and gave the example of her spending time at the beach while in her home country of Costa Rica; she showed her beach bag and other artifacts. I shared that my family enjoyed going on road trips and explained that my artifact would be a car and a roadmap.

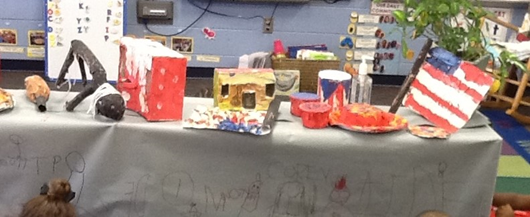

The second evening the families worked on creating a physical representation, an artifact, of their family and/or family heritage using supplies we had at school; paper, cereal boxes, soup cans, etc. The only rule for the artifacts was that they had to be handmade, nothing could be store bought. There was so much excitement, so many conversations and a busy hum filled the room! The third and final evening was a potluck celebration where each family shared their artifact and story with the group, the children presented a song, and we celebrated with a meal. I shared my car and road map representing our love of road trips, my students also shared their various artifacts as did all of the teachers. Artifacts were displayed on tables for all to see. Once everyone shared, we had our meal which was the annual Thanksgiving celebration.

As I walked around, I heard laughter, families making connections with one another and sharing stories! It was truly joyful!

What would we do different?

We were so eager for the project that we held the events in one month! We realize that having the meetings so close inhibited attendance, especially for the second meeting. The next time we do this, we will space out the meetings over a couple of months or over six weeks.

Closing thoughts

As noted above immigrant families and families of color are often viewed through a deficit lens where what they do not posses is highlighted, for example; families do not know English or they live in a high poverty area. One of our main goals for the Family Heritage Night was for families to uncover their own riches and recognize that they indeed posses knowledge, skills, and strategies that will help their children succeed in school. Engaging the undergraduate students helped them see this firsthand and also helped them see that family engagement is not scary. Finally, if we approach our families with love and respect and demonstrate that in everything that we do and say, our families begin to trust us and a trusting relationship with families is the foundation upon which everything is built.

References

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Julia López-Robertson is a Professor of Instruction & Teacher Education at the University of South Carolina.

Rocio Herron is a Pre-K teacher Jackson Creek Elementary School.