As a follow up to her webinar, Brooke Hardin expands on her resources for using multi-modal writing responses to engage students in writing.

In twenty years of teaching English Language Arts, helping students discover their “writerly life” has remained a passion. To live a writerly life means that individuals write often and with a fair amount of ease, that they see their everyday ordinary lives brimming with writing topics, and that they can use writing to reflect their ideas and potentially gain new ones. In order to begin to live a writerly life, one must be motivated to write. As teachers, engaging students in writing tasks can often be a challenge, but certain elements increase both students’ motivation for writing and their efficacy for writing tasks. Student choice in topic, modeling of strategies and techniques, consistent time to share, give, and receive feedback on writing, and invitations to write in varying modes have all been identified as ways to more likely engage students in writing. This post serves to provide strategies related to the latter idea, using various modes for writing and how these modes might inspire students to write and deepen their knowledge of disciplinary content.

What is Multimodal Writing? What Might it Look/Sound Like?

Multimodal texts are print-based and digital texts using more than one mode or semiotic resource to present meaning; mode is defined as a socio culturally formed resource to make meaning (Kress, 1010; Serafini, 2015). Authors have been exploring multimodal response for over a decade and have seen its potential to engage students in personal response and critical analysis of literature, while also developing their appreciation of genres (Dalton & Grisham, 2013). Expanding students’ literacy palette to include the modes of image, video, audio, and writing offers them more choices for how to develop and express their thinking about reading. When readers write about, interpret, or respond in some fashion to their transaction with a text, a new text is produced as the reader-turns-writer; that is, a writer or creator who seeks to express that experience with the text (Rosenblatt, 1994). Writing in a poetic form or creating a digital design as an aesthetic response to the reading positions the reader-turned-writer to adopt an aesthetic stance in which the student’s attention is focused on the lived-through experience of the reading: the emotions, moods, intuitions, attitudes, and tensions connected to the ideas and characters embodied in the text (Rosenblatt, 1994). Thus, one of the benefits of multimodal writing tasks is their potential to deepen comprehension and/or content learning.

One strategy for multimodal writing is called a half-and-half portrait (see Image 1). To create this piece, a student would first “write” the portrait about themselves. The portrait is a visual representation of an individual done by drawing one half of the person’s face using physical features (i.e., hair style, eye color, nose shape) and then filling in the other half of the face with images, quotes, or other ideas that relate to the person’s attributes, interests, life experiences. Once a student has created a half-and-half portrait about themselves, they can apply the strategy to a character from text, historical or present-day figure, or any other person. For example, the physical side of the portrait is created using the features visualized by the reader based on descriptions in the text. The other half of the character’s face uses images and other ideas related to the character and inspired by evidence from the text. For example, students might read the middle grades novel Refugee by Alan Gratz, which portrays the refugee experience of three distinct, fictional adolescent characters. Students reading this novel could further explore and demonstrate their understanding of these characters through the creation of a half-and-half portrait (see Image 2).

Image 1: Personal ½ and ½ Portrait (created by author)

Image 2: Isabel from Refugee (created by author)

In addition to creating the portraits, students can also create video or audio recordings that explain the thinking behind their multimodal writings. Teachers might ask students to discuss both the materials used to create the portraits and the ideas represented in the portraits. In multimodal writing using a visual art form such as this portrait, selection of materials and images or quotes used should be as intentional as word choice is in written texts. An example of my explanation for my half-and-half portrait can be found using this link.

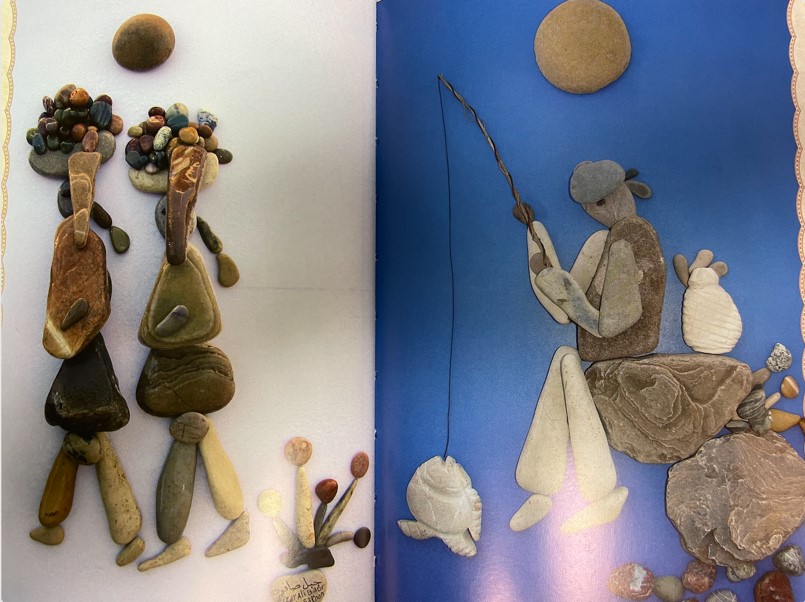

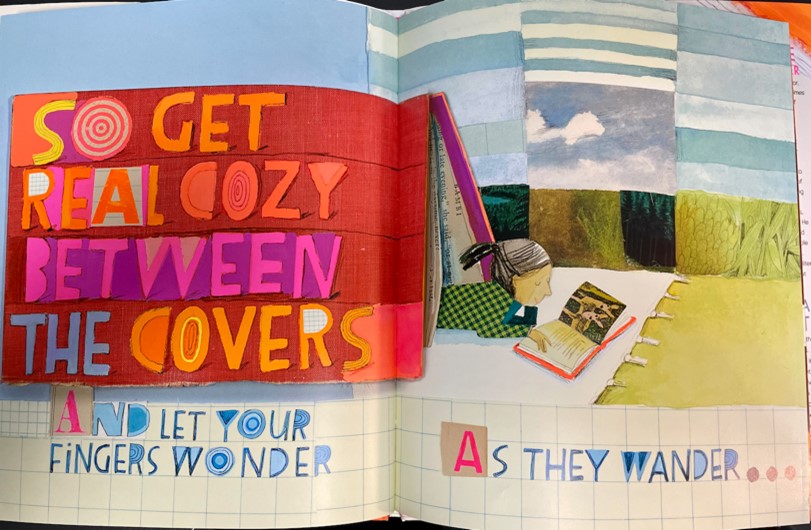

As with any new genre of writing, students need mentor texts they can reference for ideas and inspiration. Picture books, especially those that have been recognized for their illustrations, serve as some of my favorite mentor texts for multimodal writing with visual art (see Images 3 and 4).

Image 3: Illustrations made with stones in Stepping Stones: A Refugee FAmily’s Journey by Margaret Ruurs

Image 4:

Illustrations made with layered collage featuring book pages,

tattered book covers, neon paints, and cloth in How to Read a

Book by Kwame Alexander and illustrated by Melissa Sweet

Engaging Students in Writing with Poetry

Poetry is another genre that often engages students in writing tasks. Poetry is subjective and its structure can vary. Some forms, like haiku, have a particular form, but poetry can also be as simples as a collection of a person’s favorite words. The rules of writing become more relaxed in different types of poems, which allows students to tap into their creativity and use their voice to play with words, line breaks, and the appearance of the poem. Many poems are what I call “bite-sized;” thus, they are also less intimidating to write for more reluctant writers.

Definition Poems

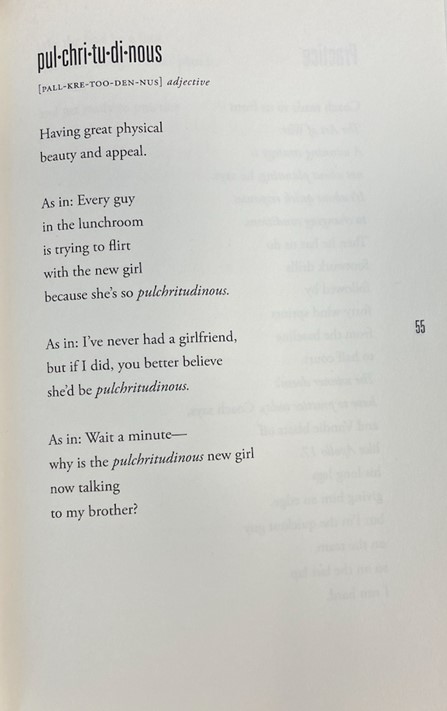

Definition poems are a specific type of poetry that follows a form but also holds space for students to use craft moves and have agency with the writing. This form of poetry is inspired by some of the pages from the middle grade novel The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (see Image 5). Written in verse, the novel features several poetic styles, including definition poems, that might serve as mentor texts for students poetic writing. The definition poem invites students to engage in writing while also enhancing their vocabulary knowledge and using learned content to create something new.

Image 5: Definition poem from The Crossover

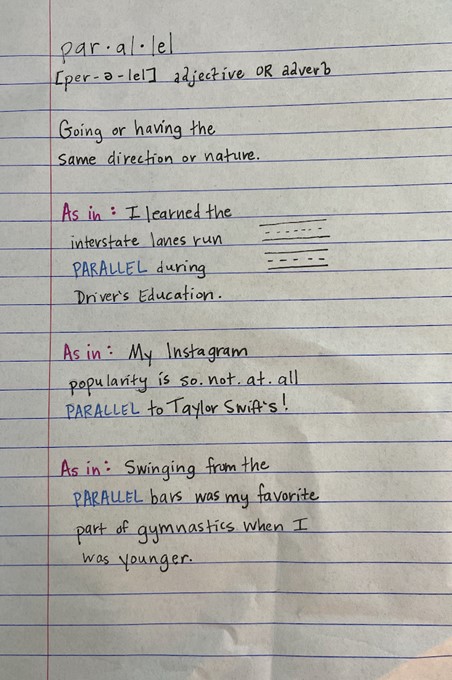

When teaching students to write definition poems, teachers should use the same principles they would use with teaching any other genre. Reference the mentor text, such as one of Alexander’s poems from The Crossover, and engage students in inquiry by asking them to take notice of how the author wrote the poem – that is, to think about and name aloud the “ingredients” used in the poem and what might be required for someone else to write the same style of poem. For example, teachers would point out how each stanza begins with “As in:” and how the vocabulary term is used in each stanza. Teachers might use a shared writing approach to co-author a definition poem with the whole class and invite students to co-author this kind of poem in pairs before they write one independently. Again, this kind of poem can be used with vocabulary from novels students read and to other content areas. See Image 6 for an example definition poem written about the math term parallel. As seen in the example, the poem offers students the opportunity to sustain their thinking about a word and its meaning and invites them to see how vocabulary terms are relevant to their lives. Additionally, these kinds of poems can serve as a piece of writing in a larger multimodal piece. For example, students might be invited to illustrate each stanza of the poem to add a visual layer.

Image 6: Example definition poem (created by author)

Golden Shovel Poems

Golden shovel poems are a poetic form created by Terrance Hayes and inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem, “We Real Cool.” To write a golden shovel poem, the writer must do the following:

- Take a line or lines from a poem you like.

- Use each word in the line as the end word in each line of your poem.

- Keep the words in order.

- Give credit to the original poet.

- The new poem does not need to be about the same subject as the original poem, but they can be related in some way if the writer chooses to do so.

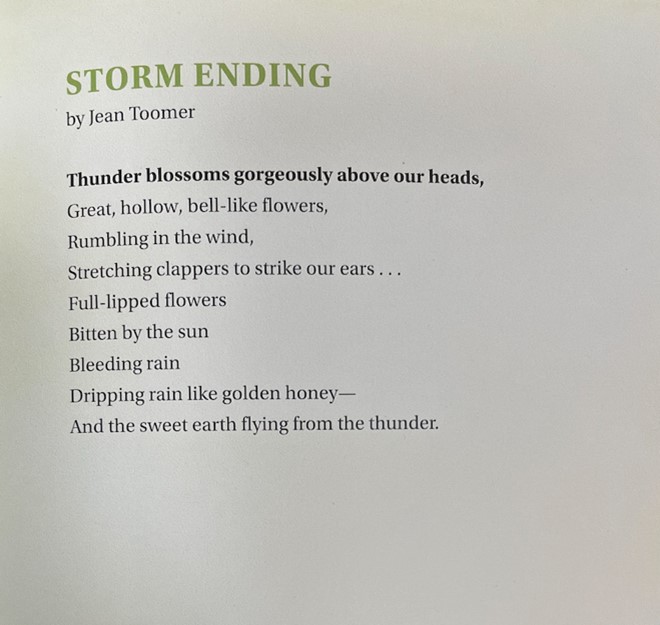

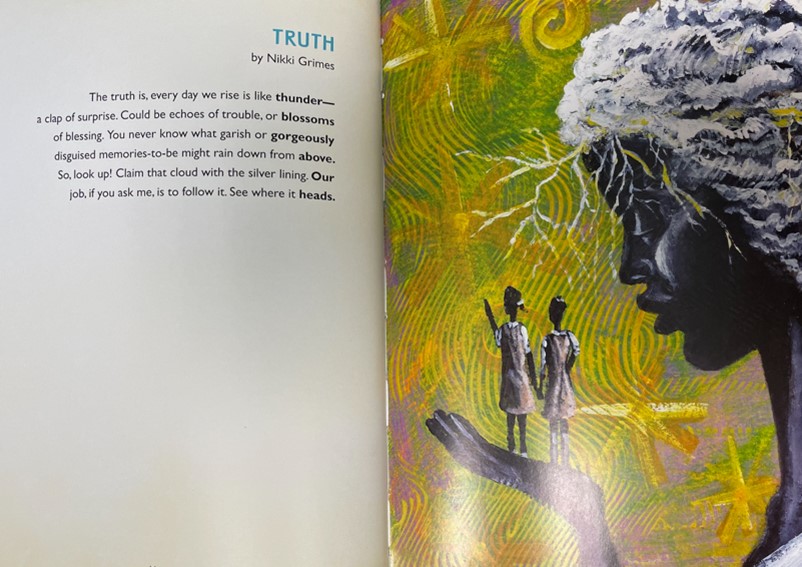

Inspired by Terrance Hayes, Nikki Giovanni wrote the book One Last Word, which is a book of golden shovel poems about the Harlem Renaissance. Using two of the poems from this book as mentor text (see Images 7 and 8), teachers can help students see how the poem is written and gain inspiration for their own writing.

Image 7: “Storm Ending” from One Last Word

Image 8: “Truth,” a poem written by Nikki Giovanni using a line from “Storm Ending” by Jean Toomer

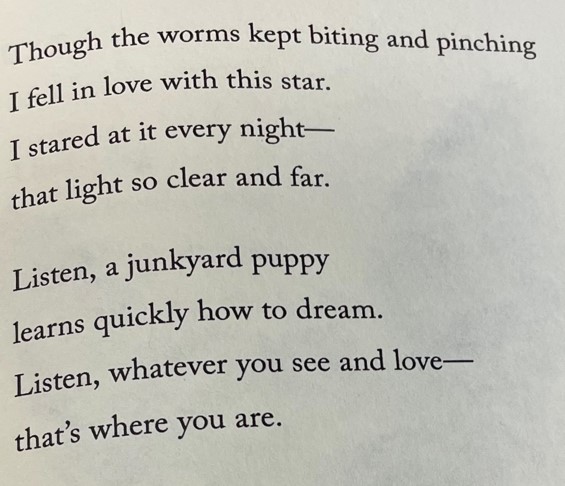

Teachers should immerse students in reading many different poems, invite them to bring in poems – including song lyrics – that they admire, to gain ideas and inspiration for writing their own golden shovel poems. Again, teachers may want to scaffold this kind of writing and co-author poems with students in a whole group setting before tasking students with writing one on their own. Golden shovel poems are complex but also provide students an opportunity to play with word choice, syntax, line breaks, and be creative in their writing. Inspired by a poem from Mary Oliver’s Dog Songs, I show students my own attempt at this poetic form (See Images 9 and 10).

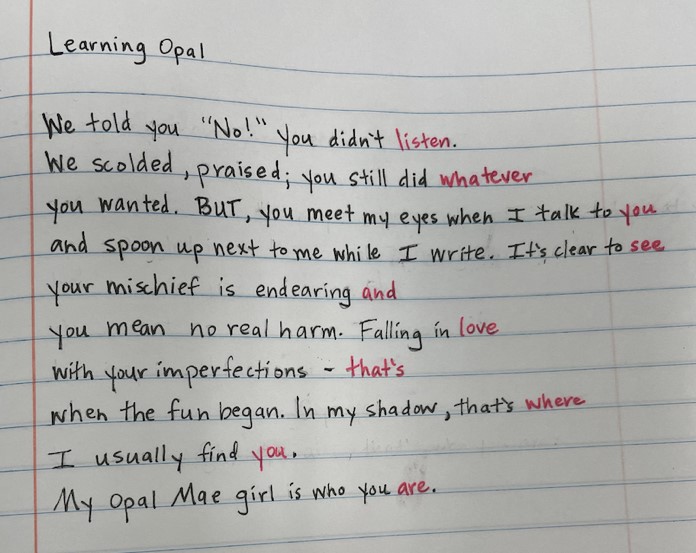

Image 9: Excerpt from “Luke’s Junkyard Song” by Mary Oliver

Image 10: Golden shovel using the last two lines from “Luke’s Junkyard Song” (created by author)

Final Thoughts

No matter the strategy used, teachers must remember to embrace vulnerability and write alongside of students, both modeling the techniques and making the cognitive side of writing – word choice decisions, art medium choices, etc. – become evident and accessible for students. Writers need to see and hear other writers engaged in writing to discern the process and be inspired. Writers also need room for creativity. Each of the strategies offered here provides space for creativity and the opportunity for students to express themselves while also learning and showing their content knowledge.

References

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London, UK: Routledge.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. Ruddell et al. (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Serafini, F. (2015). Multimodal literacy: From theories to practices. Language Arts, 92(6), 412-423.