Dr. Stephanie Lemley develops socio-economic awareness as students experience disciplinary literacy in an agricultural setting. Read more about Dr. Lemley at the end of her blog.

As a literacy teacher educator and a PI or Co-PI on three United States Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA/NIFA) grants for professional development in agricultural literacy, I have been fortunate to work with teachers across Mississippi on infusing agricultural literacy into their classroom instruction. Two of my grants have enabled me to create a summer professional development and then host the teachers on the university campus in the fall and spring for follow-up days. This school year I am working with colleagues from Agricultural Education, Leadership, and Communication, Poultry Science, and Food Science and 28 amazing K-12 teachers from across the state. The teachers’ experiences range from starting their first year of teaching to 25+ years in the classroom. We are currently working with content areas such as special education (e.g., gifted and inclusion classrooms), mathematics, ELA, science, welding, and agriculture. During a four-day, intensive workshop this summer, the teachers learned how to incorporate poultry science and food science content knowledge and lab investigations, literacy instruction, and socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills into their classroom.

This is important because most Americans are agriculturally illiterate (Taylor, 2021, July 7). In fact, in most cases, individuals are three generations removed from the farm, which means more and more people are not aware of where their food comes from (Brandon, 2012, March 30). The American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (2012) has created pillars of ag literacy, one of which is understanding the connections between agriculture and the environment. Hubert et al. (2000) posited that teachers can use agriculture as a topic to teach about the environment and the world around them. This focus on the natural world can also be a great way to infuse socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills into the curriculum as well (Carter, 2016).

Socio-emotional learning (SEL) skills is an “umbrella term used to describe psychological constructs such as personality traits, motivation, or values” (Danner et al., 2021). When teachers teach these skills to their students, they are helping them become efficient workers who know how to build trusting relationships with others, cope with change, serve as leaders, and produce creative solutions to solve problems (Danner et al., 2021). These skills include responsible decision making, self-awareness, self-management, and relationship skills (National University, 2022, Aug. 17). Agricultural topics are the perfect place to teach socio-emotional skills to students because of the diversity of content and emphasis on problem solving. For example, when discussing food choices, students are practicing the socio-emotional skill of responsible decision making; when working in groups to complete labs, students will be practicing the socio-emotional skills of social awareness and relationship skills.

Here’s an example of how teachers who work with me in the four-day workshop investigate the topic of ‘hunger in Mississippi’ through book readings (How Did That Get in My Lunchbox?: The Story of Food by Chris Butterworth, Maddi’s Fridge by Lois Brandt, and Free Lunch by Rex Ogle), online investigations, and proposed solutions to food waste in local communities. We tied the topic of hunger to a variety of Mississippi state science standards.

Table 1. Example Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Science

| Example Science Standards |

| L.K.1A Students will demonstrate an understanding of living and nonliving things. L.K.3A Students will demonstrate an understanding of what animals and plants need to live and grow.L.2.3A Students will demonstrate an understanding of the interdependence of living things and the environment in which they live. L.2.3A.1 Evaluate and communicate findings from informational text or other media to describe how animals change and respond to rapid or slow changes in their environment (fire, pollution, changes in tide, availability of food/water). L.5.3B Students will demonstrate an understanding of a healthy ecosystem with a stable web of life and the roles of living things within a food chain and/or food web, including producers, primary and secondary consumers, and decomposers. L.5.3B.1 Obtain and evaluate scientific information regarding the characteristics of different ecosystems and the organisms they support (e.g., salt and fresh water, deserts, grasslands, forests, rain forests, or polar tundra lands). L.5.3B.2 Develop and use a food chain model to classify organisms as producers, consumers, or decomposers. Trace the energy flow to explain how each group of organisms obtains energy. L.7.3 Students will demonstrate an understanding of the importance that matter cycles between living and nonliving parts of the ecosystem to sustain life on Earth. L.7.3.5 Design solutions for sustaining the health of ecosystems to maintain biodiversity and the resources needed by humans for survival (e.g., water purification, nutrient recycling, prevention of soil erosion, and prevention management of invasive species). |

On the first day of the workshop, teachers investigate ‘hunger’ in their local school district, local community, and the state. First, they searched “hunger in Mississippi” and looked at sites such as Mississippi Food Network (https://www.msfoodnet.org/about-us/hunger/) and Feeding America (https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/mississippi). Then, they searched “hunger in [insert county or city name]. Finally, they looked at hunger in their own school district. One source of data they looked at was from the Mississippi Department of Education (https://www.mdek12.org/sites/default/files/documents/OCN/2023/SFSP/free_and_reduced_data_report_2022-23.pdf). They wrote information that they found on sticky notes and then shared out the information with the rest of the class.

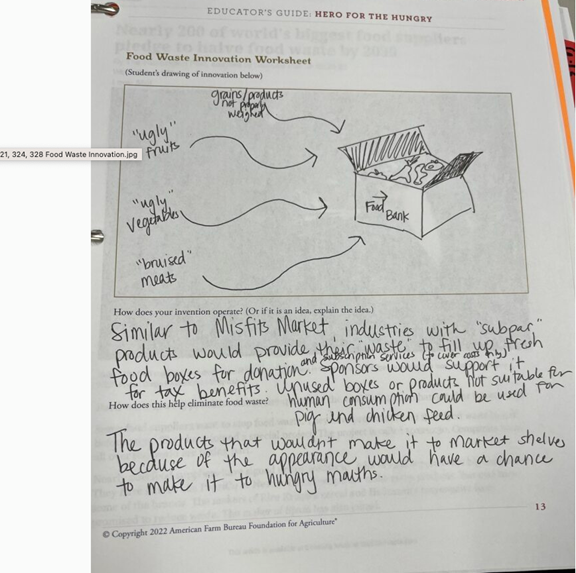

This initial foray into hunger allowed the teachers to learn more about this impactful issue across the state. For many, it reinforced information they already knew about their own community, but it was eye-opening for many to see how big of a problem it is statewide. For example, in looking at the free and reduced lunch data, many were surprised that some of the perceived ‘affluent’ counties in the state still had multiple schools with high percentages of free and reduced lunch. As such, this topic introduced them to a part of environmental and agricultural literacy—food literacy (Siegner, 2019). Food literacy is defined as “the scaffolding that empowers individuals, households, communities, and nations to protect diet quality through change and strengthen dietary resilience over time. It is composed of a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills, and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare, and eat food to meet needs and determine intake” (Vidgen & Gallegos, 2014, p. 54). In addition, this investigation reinforced the SEL skill of social awareness—showing understanding and empathy to others—because it required them to reflect on their own students and how many of them might come to school hungry and need additional sustenance to stay focused during the school day. The second day, the teachers worked in groups to create an innovative way to address food waste in communities. This activity required them to think scientifically and utilize precise science and engineering terminology and design methods to create their solution. We chose this activity because many of the teachers had recently talked about how much food was wasted either at restaurants or at their schools during lunch and how they would like to put some of that food to good use in their community.

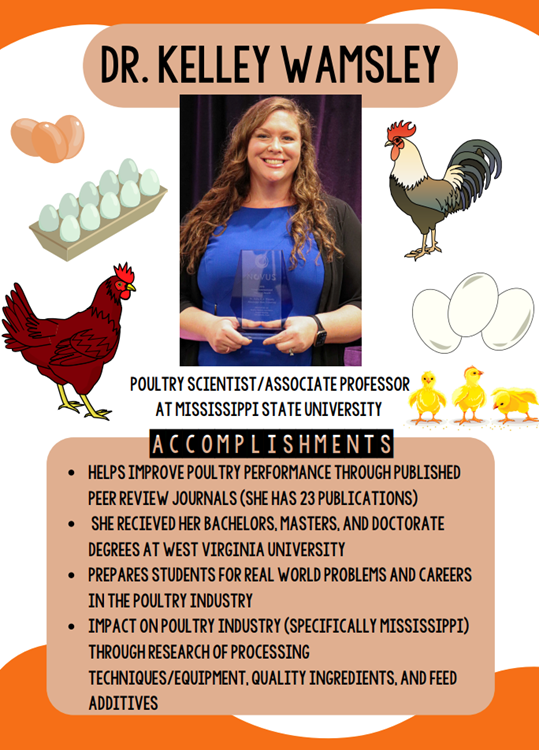

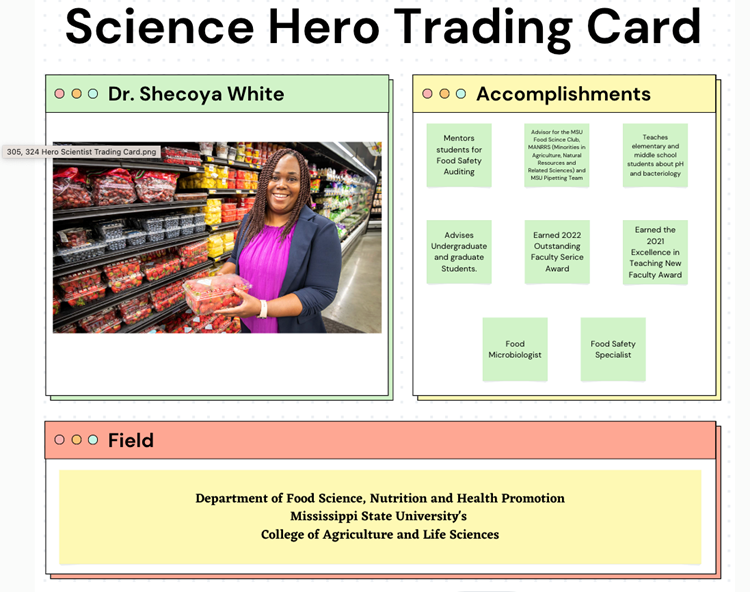

On the third day, the teachers, in groups, created hero scientist cards on a food science or poultry science scientist who has done work that impacts hunger in the state. This activity required the teachers to showcase a scientist who has had a positive impact in improving Mississippi’s environment and its agricultural industry. This activity also required the teachers to not only work on SEL skills such as relationship skills and self-management, but also to use discipline-specific terminology related to the food science or poultry science field when adding information to their trading card.

After the summer PD, the teachers returned to their classrooms and implemented lessons that we had done with them in their own teaching. Many used the agriculture texts to teach SEL skills and the food supply. They used the strategies and activities we taught them, and they also shared their new knowledge with their colleagues at their school site or in their district. During the fall follow-up day, the teachers continued to investigate hunger, but this time looked at it not just from a regional and state perspective but also a worldwide perspective. I chose to focus on hunger more broadly this time to show them how they could have their students consider hunger in their own community first (as we did in the summer) but then have them realize that hunger is not just a Mississippi problem—in fact it is a problem in our region, country, and world as well. The lesson and activities I implemented were also tied to state standards in the science, mathematics, social studies, and ELA standards.

Table 2. Example Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards.

| Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Social Studies | Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for Science | Mississippi College-and-Career Readiness Standards for English/Language Arts |

| 6.8 Examine how humans and the physical environment are impacted by the extraction of resources and by natural hazards 3. Assess the opportunities and constraints for human activities created by the physical environment. | ENV.4 Students will demonstrate an understanding of the interdependence of human sustainability and the environment. ENV.4.3 Enrichment: Research and analyze case studies to determine the impact of human‐related and natural environmental changes on human health and communicate possible solutions to reduce/resolve the dilemma. | RI.6.7 Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue. |

First, they watched a video about the area of Memphis, TN, that is a food desert (see link in resources). The video was then tied into the National Agriculture in the Classroom lesson on ‘Hunger and Malnutrition (see link in resources). In this lesson, students investigate the importance of eating a variety of nutritious foods and explore diets around the world. The teachers were introduced to more health and food science terminology such as nutrient, undernourishment, food bank, staples, accompanying foods, and hunger. They then used the National Geographic website, What the World Eats, and answered the following questions:

- Which country consumes the most calories in a day?

- Which country consumes the fewest calories in a day?

- Which country consumes the most 1) red meat, 2) grain, 3) sugar, and 4) fat?

- Which country consumes the least 1) red meat, 2) grain, 3) sugar, and 4) fat?

After they had worked on this investigation, we discussed what they found across groups. These activities continued reinforcing SEL skills such as social awareness, relationship skills, and self-management as they negotiated group tasks. It also provided them an opportunity to continue to investigate environmental and agricultural literacies specifically food literacy. This is important because part of being agriculturally literacy involves understanding the food system and the importance of plants and animals to our environment. The workshop concluded with the teachers being introduced to two short films from Mississippi State University Films: one of which was on food insecurity, and one of which was on a local school district response to schools shutting down during the COVID-19 pandemic and getting food to the students who relied on school lunch as part of their food sources daily. These videos provided a real-world example of people using socio-emotional skills, such as responsible decision making, compassion, and relationship-building to make a difference in the local community. Further, the teachers learned about ways that community members are stepping up to help end food insecurity in their own backyards through the creation of local farmers markets and other means. This can help further develop their agricultural literacy knowledge because they have a deeper understanding of the food system.

I wanted to share these lessons and resources with my teachers because I wanted to show them how they could help their students become more agriculturally literate with a topic that is relevant to everyone—hunger and food. Over the school year, some teachers have emailed me to share how impactful these agricultural literacy SEL lessons have been for their students, particularly reading the book Free Lunch with their class and then investigating hunger in their community and where food comes from. Others expressed this in their delayed post follow up survey. For example, one teacher wrote that creating trading cards has been the most successful activity with their classes. They noted, “The kids love it and are all 100% into it.” Creating the trading cards on scientists allowed students to showcase their learning in a creative way. Another teacher wrote that participating this year helped them have “more opportunities for students to learn agriculture in different cultures, bringing awareness of food deserts and waste.” The teacher said the students particularly enjoyed exploring the National Geographic website and watching the videos about Memphis and food insecurity in the Mississippi Delta; learning about this topic had them think about what nutritious food was available to them on a regular basis outside of school. Another teacher wrote participating in the professional learning gave her “an enhanced sensitivity to food deprivation within my classroom.” These lessons over the past year opened this teachers’ eyes to hunger in their own students and the teacher has made it a priority to have nutritious snacks available for the students. Two others wrote, “All of the SEL!” for their response. Finally, one additional teacher wrote, “From ACRE 2.0, I’ve already used interactive simulations and hands-on experiments in my class. Next, I plan to add collaborative projects and real-world problem-solving tasks. These activities deepen understanding and build teamwork skills. Additionally, I’ll integrate more tech tools for personalized learning.”

References

American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture (2012. Pillars of agricultural literacy. https://www.agfoundation.org/files/PillarsPacket062016.pdf

Brandon, H. (2012, March 30). At what cost the disconnect between agriculture and the public? https://www.farmprogress.com/commentary/at-what-cost-the-disconnect-between-agriculture-and-the-public-

Carter, D. (2016). A nature-based social-emotional approach to supporting young children’s holistic development in classrooms with and without walls: The socio-emotional and environmental education development (SEED) framework. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 9-24.

Danner, D., Lechner, C.M., & Spengler, M. (2021). Editorial: Do we need socio-emotional skills? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-3. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723470.

Hubert, D., Frank, A., & Igo, C. (2000). Environmental and agricultural literacy education. Water, Air, Soil Pollution, 123, 525-532. https;//doi.org/10.1023/A:1005260816483

National University. (2022, August 17). What is social emotional learning (SEL): Why it matters. https://www.nu.edu/blog/social-emotional-learning-sel-why-it-matters-for-educators/

Siegner, A.B. (2019). Growing environmental literacy: On small-scale farms, in the urban agroecosystem, and in school garden classrooms [Doctoral dissertation, University of California Berkeley]. UC Campus Repository. https://escholarship.org/content/qt4p16p53v/qt4p16p53v_noSplash_53f7a6e2917068410defb11335b7ac1b.pdf?t=q6z2hg

Taylor, B. (2021, July 7). Ag illiteracy: What happened, and where do we go from here? https://www.agdaily.com/insights/ag-illiteracy-what-happened-where-to-go/

Vidgen, H.A., & Gallegos, D. (2014). Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite, 76, 50-59. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010

Resources

Judd-Murray, R. (2013). Hunger and malnutrition (grades 3-5). National Agriculture in the Classroom. https://agclassroom.org/matrix/lesson/388/

Mississippi Department of Education. (2023). Mississippi college-and-career readiness standards. https://www.mdek12.org/OAE/college-and-career-readiness-standards

Team, I. W. D. (2024, February 14). The hungriest state. MSU Films. https://www.films.msstate.edu/series/the-hungriest-state

What the world eats. National Geographic. (n.d.). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/what-the-world-eats/

YouTube. (2019, November 20). The food deserts of Memphis: Inside America’s hunger capital | divided cities. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6ZpkhPciaUxs

Funding Statement:

This work is supported by the USDA/NIFA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, AFRI Agricultural Workforce Training Priority Area, award # 2022-08873.

About the Author:

Dr. Stephanie M. Lemley is an Associate Professor of Content-Area Literacy and Disciplinary Literacy Instruction in the elementary education program in the Department of Teacher Education and Leadership in the College of Education at Mississippi State University. She is the recipient of three USDA/NIFA grants on professional development in agriculturally literacy (either as PI or Co-PI) and in the last four years has worked with approximately 150 K-12 teachers across the state, either virtually or through face-to-face instruction, on infusing agricultural literacy into their classroom instruction. She can be contacted at smb748@msstate.edu .