This blog is written by Lesley Roessing suggesting that a variety of texts can be used to teach historical events still impacting the world today. Read more about Lesley at the bottom of her post.

No historical event may be as unique and complicated to discuss and teach as the events of September 11, 2001, the day terrorists crashed planes into, and destroyed, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. At the time of this event, no child in our present K-12 educational system was yet born, but, in most cases, their parents and educators would have been old enough to have some knowledge of, and even personal experience with, these events, making this a very difficult historic event for many to teach. However, with the devastation and impact of these events on our past, present, and future and as ingrained a part of history these events are, they need to be discussed and understood as much as possible.

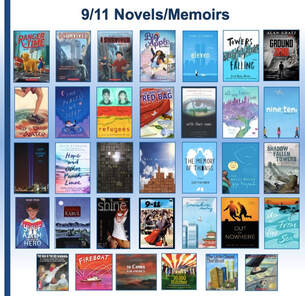

An effective way to learn about these events is through story. Powerful novels have been written about this tragedy, for all age levels and, fascinatingly, each presents a different perspective of the events. Some take place during September 11, some following the events, some a few years later or many years later, and a few include two timelines. Many take place from the perspectives of multiple characters.

On September 11, 2021, YA Wednesday posted my guest-blog “Novels, Memoirs, Graphics, and Picture Books to Commemorate September 11th.” In this blog, I interviewed authors and reviewed and recommended 24 texts and six picture books.

Since then, I have read two additional texts:

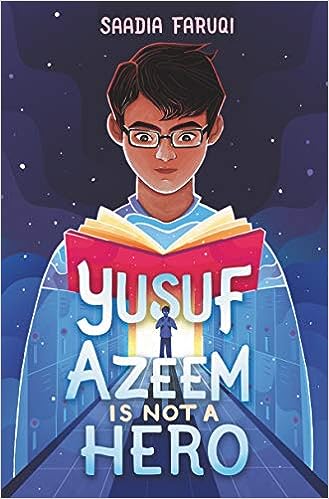

Yusuf Azeem is Not a Hero by Saadia Faruqi

“Suspicion of those unlike us is common human behavior. We don’t trust who we don’t know. But yes, 9/11 was terrible, and it really fueled the fire of hatred in this country.” (184-5)

Sixth grader Yusuf Azeem was born in Texas and is an American; his mother was also born in America and his father was a Pakistani immigrant who runs the popular A to Z Dollar Store in town (and a somewhat a local hero after capturing an intruder threatening his store and customers). The family is Muslim, but, understandably, Yusuf is shocked when sixth grade begins with threatening notes in his locker. When one says, “Go home,” he is hurt and confused. Frey, Texas is his home. Surely the notes are meant for someone else.

This is a novel that may benefit from some background on the events of September 11, 2001, since the action takes places in 2021 but, read individually, Ausuf’s uncle’s journal helps to fill in information. The importance of this particular novel is that it demonstrates that, for some of our citizens and students, “Twenty years. So much time. But things haven’t really changed at all.” (48) One of the major events in the story—when a little computer in his backpack beeped and, instead of questioning him and investigating, Ausuf is thrown in jail for twelve hours—is based on a real event from 2015 where Ahmed Mohamed, a Muslim 14-year-old, was arrested at his high school because of a disassembled digital clock he brought to school to show his teachers [https://www.cnn.com/2015/09/16/us/texas-student-ahmed-muslim-clock-bomb].

It is vital that our children learn about 9/11 because, as Yusuf’s mamoo says, “History informs our present and affects our future.” (81)

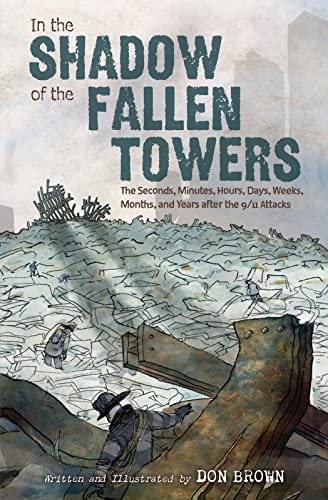

In the Shadows of the Fallen Towers by Don Brown

Don Brown’s graphic novel recounts events following the 9/11 attacks on the Towers and the Pentagon from the moment of the “jetliner slamming into the North Tower of the World Trade Center” to the one-year anniversary ceremonies at the Pentagon, in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, and at Ground Zero. It also covers the fighting of U.S. troops in Afghanistan and the capture and interrogation of prisoners from an al-Qaeda hideout in Pakistan.

The drawings allow readers to bear witness to the heroism of the first responders, firefighters, and police as they move from rescue to recovery over the ten months following the attacks and learn the stories of some of the survivors they saved. It is the story of the nameless “strangers [who] help[ed] one another, carrying the injured, offering water to the thirsty, and comforting the weeping.” (23)

We learn and view details that we may have not known, such as “Bullets start to fly when the flames and heat set off ammunition from fallen police officers’ firearms,” (11) the “Pentagon workers [who] plunge[d] into the smoke-filled building to restore water pressure made feeble by pipes broken in the attack,” (36) and former military who donned their old uniforms and “bluff[ed their way] past the roadblocks” to “sneak onto the Pile” to help. (50, 52)

For more mature readers this book adds to the story of 9/11 in a more “graphic” way.

I have taught a unit on NINE ELEVEN through book clubs in multiple schools from grades 5 through 9 in both ELA and Social Studies classes. Children and adolescents have felt comfortable these sensitive and challenging concepts and examining these troubling events and some of the ensuing difficulties, prejudices, and bullying, through the eyes of characters who are around their ages, some readers sharing personal stories in their small collaborative groups. I am thankful for the authors who have allowed our children to experience these events in a safe and compassionate way. I have presented these novels and strategies and lessons for reading through book clubs at local workshops and national conferences. I included my 9/11 Book Club unit as a chapter in TALKING TEXTS: A Teacher’s Guide To Book Clubs Across The Curriculum.

Condensed and reproduced with permission from https://www.literacywithlesley.com/blog posted on September 2, 2023.

Follow her website, created to support educators—teachers, librarians, and parents, at https://www.literacywithlesley.com/