Ms. Kristie Camp is a PhD candidate who has taught English Language Arts for 26 years. Her webinar provides a picture of how to grow environmental literacy in an outdoor classroom.

Tag: Collaboration

Flashback to our theme on Financial Literacy! Due to publisher error, Derrick Shepard’s blog was delayed. So, it is now time to hear how Dr. Shepard supports this quote by Jane Bryant Quinn: “No one is born with a mind for personal finances.” Read more about our author at the end of his blog.

Sit with the above quote for a second before moving on. What comes to your mind after you read it? What feelings are elicited? Does the quote speak to you, to the students you are trying to instill a sense of understanding of financial literacy?

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2019) defines “Financial literacy as knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, as well as the skills and attitudes to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts to improve the financial wellbeing of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life.”

The definition is holistic, but it is important to remember that a person’s understanding of financial literacy rests in their knowledge, understanding, attitudes toward financial literacy, and skills to implement a plan that incorporates all three. Now, revisit your thoughts and feelings about the above quote. Did anything change?

There is no denying that individuals need a basic understanding of financial literacy to navigate this capitalist society. Understanding how one’s credit score can impact everything from mortgage rates to credit card rates to the amount you pay for automobile insurance can help save money for the future. As educators, it is incumbent upon us to teach the 3 Rs and relay life skills, including financial literacy, to our students to help them grow into productive and responsible citizens. But how do we do it?

Our students live in a 24-hour, 365-day-a-year social media cycle that never ends. They are bombarded with messages every time they pick up their smartphones, and financial messages (e.g., how to make money) are prominent in the messaging. What I call “salespeople” (and I am being kind) promise riches with little to no effect. Ya, right. Other messages are more “old school” in that they speak to one’s athletic, musical, or artistic abilities to achieve the American Dream. Have you seen some commercials or music videos lately? An example of this is one of Toyota’s commercials for its Tundra Capstone. The actors promote the truck, which is nice and comes in at around $75000 as if it’s a status symbol to achieve to be accepted in the group. As educators, we know group interaction and acceptance are important for one’s development, especially during the pre-adolescent and adolescent years.

So, what messages are students receiving outside of the classroom regarding money?

Reflecting stopping point.

As educators vested in their students’ success, what do you know about them? I bet it’s a lot. You know their likes and dislikes. You know what their home lives are like to a degree. You know them, not as an aggregate reflection of a class roster. No, you know them as individuals with strengths and areas of growth. In knowing and considering this, remember this:

Financial Literacy IS NOT one size fits all.

To the best of your ability, you must consider individual demographics (e.g., racial identity, social class, ethnicity) when constructing an Individual Financial Education Plan (not be confused with an IEP, pun attended). Why is it so important that students’ financial education be individualized as possible? As Frederick Nietzche put it, “‘This-now my way: where is yours?” Thus, I answered those who asked me ‘the way.’ For the way-does not exist.!” As with an IEP, one’s Individual Financial Education Plan (IFEP) needs to be individualized because we all have different backgrounds, values, hopes, and aspirations.

I am not going to leave without some recommendations and resources.

The Psychology of Money (2021) by Morgan Housel is a terrific resource for taking a deeper dive into why we make the decisions we make regarding money. I tweaked his recommendations from the book to fit your students’ age demographics.

- Have students not be too hard on themselves when things go wrong financially.

Setting financial goals is the first step, but as with any goal, things can, and most likely will, go wrong, and mistakes will be made. It is our responsibility to instill a sense of forgiveness in them.

- Focus on wealth and not the ego.

Students are bombarded with messages to spend money. You have to have that new phone. Making saving cool can be (is) hard while living in an instant gratification society. Media does not make it any easier. However, we still need to figure out what makes our students tick and how to circumvent those messages to the best of our ability. Again, we know our students better than some algorithms. 😊

- Time is their friend.

Saving $10 a month does not seem like a lot; however, compound interest is the 8th wonder of the world. Use a time horizon calculator to show them what savings look like today and in the future. There are tons of time horizon calculators out there. Here’s one: https://smartasset.com/investing/investment-calculator

- You can replace money, but you cannot replace time.

Time is as precious as money. You can always get back money, but time is gone. We must impress upon our students to use their time wisely when it comes to finances. I can imagine you already do this in your role as an educator. Just put a twist on it and add the money.

- Be nicer and less flashy.

This gets into social-emotional learning. Housel (2020) states that one “is impressed with possessions as much as you are (p. 209). He argues, instead, that we are looking for respect and admiration from our peers (Housel, 2020). Having kindness and being respectful are other ways to gain respect from our peers.

- Save, baby, save!

Go back to recommendation #3.

- Help your students define what “success” means for them.

I am going to address this recommendation with my counselor educator hat on. Part of being a good counselor is to be open and congruent with clients. As the saying goes, “Clients will only go as deep as you are willing to go with yourself.” With that in mind, we need to remember the core condition of Unconditional Positive Regard (for our students and ourselves) when we teach financial literacy. We need to be Congruent and be who we are with our students when we teach financial literacy, and, finally, we need to show Empathy for those, including ourselves, who are struggling to better themselves but not knowing what they do not know.

- Help students define their “game.”

Financial success looks different for every student. What one considers a success may be an overreach or underreach for the next. There is no way. But, we can help our students reflect, critically think, and plan for a future that fits them.

Finally, I want to leave you with some financial resources that may assist you and your students in gaining a better understanding of personal finance.

The National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE) champions effective financial education. They are the independent, centralizing voice that provides leadership, research, and collaboration to advance financial well-being.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is a U.S. government agency dedicated to ensuring you are treated fairly by banks, lenders, and other financial institutions.

Khan Academy offers practice exercises, instructional videos, and a personalized learning dashboard that empowers learners to study at their own pace in and outside the classroom.

- 15 Financial Literacy Activities for High School Students (PDFs) (moneyprodigy.com)

- https://www.kidsmoney.org/teachers/financial-literacy-activities-high-school/

I hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it for you. The financial literacy journey is complex and ever-changing. But what does not change is our duty as educators to help our students grow and develop into the individuals we know they are capable of.

This webinar features Brooke Hardin and provides resources for using multi-modal writing responses to engage students in writing.

In our educational spaces, we often break our areas of expertise down into specific subject matters. We educate, train, and certify classroom teachers in terms of grade bands and content or disciplines. Students in schools spend time blocked off in different subjects where they receive instruction in a content area and earn grades that signify their level of expertise and competence in that area.

We separate our time in the educational pathway into grade levels and content areas to make it a bit easier to certify and support educators as they work with youth. But, these artificially designed pieces end up creating silos where educators and students set up camp and develop expectations about what, why, and how we learn. This raises the question about whether we need to erase the boundaries between disciplines, or do we need to—in a sense—harden them so that students learn where they start and end and are therefore better prepared for their futures?

A transdisciplinary lens challenges educators and researchers to consider the spaces in which learning occurs and overcome established paradigms and competition within and between disciplines. 1 This post will examine the ways that education tries to carve out a space for collaboration and ambiguity between the disciplines and suggests there is a need to deconstruct assumptions made about educational structures and systems to de/re-territorialize teaching, learning, and assessment. 2

Interdisciplinarity

Some theories of education shift the focus from understanding of formal concepts to meaning-making to encourage students and educators to cross disciplinary connections. 3 As instruction moves away from traditional understandings of content areas and disciplines to craft new blended content areas (e.g. Humanities, STEM, STEAM), there is an opportunity to find content area literacies in context in other disciplines. 4 A desire to study across “individual attributes, at the nexus of institutional and material practices and textual cultures, instrumentality, and the production of agency and identity.” 5 Educators seek not for disciplinary purity and isolation, but to explore knowledge, discourse, and literacy practices around mutual areas of inquiry. 6 Instruction may also focus on teaching strategies that integrate multiple domains of knowledge into a single unit of study, such as authentic learning 7 or project-based learning. 8

In the graphic above, you can see two disciplines with their own sets of practices, skills, content, and dispositions. In an interdisciplinary perspective, educators and the content work together synergistically to understand an object of inquiry.

One way to consider this is to think about a science teacher and an art teacher working together on a unit with students. The science teacher would consider the content and curriculum they are teaching. The art teacher would think about their content and curriculum. The process or product of the interdisciplinary unit might have students use art to illustrate or creatively express content of the other discipline. This is not a bad thing, but we’re reminded of Aristotle who stated, “The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.”

Metadisciplinarity

Metadisciplinarity is the understanding of the structure of a discipline, “of what the discipline is, what it tries to accomplish, and how it tries to accomplish its aims.” 9 Metadisciplinarity goes beyond one discipline into the structural understanding of various disciplines in order to make comparisons and connections between disciplines. 11 The elements of metadisciplinarity include practices such as defining notions, generalizing ideas, drawing parallels, developing classifications, choosing proper classification grounds and criteria; to find out causal relationships, building logical reasoning and making (inductive, deductive, analogical) conclusions. 12

In the graphic above, metadisciplinarity finds the connections, or correspondence (marked with “μ”) between subsets of practices, skills, content, and dispositions from one discipline to the other.

One way to think about this is using our example of a science and an art teacher working on a collaborative unit. Teachers and students would examine and compare the similarities and differences between the two content areas. They may consider the affordances of each of of the disciplines.

Transdisciplinarity

As detailed above, educational research and practice can be framed as a spectrum starting from content area silos and a disciplinary focus to more of an integrated interdisciplinary connection that includes multidisciplinary associations. The concept of transdisciplinarity is slippery, in flux, and has a plurality of definitions. 13 One of the features of transdisciplinarity is blurring and transcending disciplines. These spaces have been shown to provide fertile grounds for exploring patterns of change, transformations, and invariants in and across content areas. 14 Transdisciplinarity breaks down the silos and pro-

vides an enriched experience that is more true to life in that disciplines are experienced

simultaneously rather than in isolation. 15

In the graphic above, transdisciplinarity involves the blending of disciplines by blending of practices, skills, content, and dispositions from one discipline to the other.

One way to think about this is with our example of a science and art teacher working together on a unit. They consider the concepts, expressions, and forms shown in art, science, and in-between. They study gardens as heterogenous assemblages where art, science, and people meet. They consider how the plants need water and cultivating in order for the garden to prosper. In their work, they include elements of art, science, and beyond. But, their work process and product is an iterative assemblage as they consider where the living sciences, and abstract nature of art meet.

This post was written by Nenad Radakovic and Ian O’Byrne. This was originally posted here. Portions of this content from our publication titled Toward Transdisciplinarity: Constructing Meaning Where Disciplines Intersect, Combine, and Shift.

Photo by Ashkan Forouzani on Unsplash

By: Lindsey Douglas, English teacher at Gettys Middle School.

Literacy is often wrongly associated with only the humanities, namely English Language Arts and Social Studies. However, as contemporary studies suggest, disciplinary literacy is a necessary educational shift to meet the demands of the twenty-first century student as they participate in literacies of varied subjects (Lent & Voigt, 2019). The heart of disciplinary literacy is an accurate understanding of how content knowledge is constructed and how literacy (reading, writing, viewing, reasoning, and communicating) supports the knowledge of the respective content (Lent & Voigt, 2019).

For that reason, I teamed up with an experienced, award-winning math educator who is considered an expert in her field. We collaborated and co-taught a lesson, with each teacher valuing the other’s expertise. While the text in Math may look different than texts in my English Language Arts class, we define a text as anything a student can see, interpret, and assign meaning.

Introducing the Lesson

Our first text of the lesson was an image. The images used in the lesson were found on reasonandwonder.com. We introduced the lesson with visual literacy in which students “read” the image to interpret, evaluate, and understand the meaning. We posed two questions for the students to prompt their thinking: What do I notice and What do I wonder? The students first worked independently. Before students began reading the text, we discussed what it means to both “notice” and “wonder.” The classes acknowledged that the skill of “noticing” is what we call observing, and that of “wonder” is to inference. Like Lent suggests, “we want students to know how to interrogate texts rather than simply read them” (Lent, 2015, p.109).

Academic discourse is a critical cornerstone of a Math Disciplinary Literacy classroom. Following the image was both a small group discussion and class discussion of the students’ discoveries. However, before discussing their findings, the Math teacher reestablished group norms.

The group norms of this classroom include:

- No one is done until everyone is done

- You have the right to ask anybody in your group help

- No talking outside your group

- No naked numbers

- Remember to play your role

- Put the question in your answer

- Say your “becauses”

- Listen to others’ ideas

- Take turns

- Be Respectful

- Confusion is a part of learning

- You have the duty to give help to anybody who asks

- Disagree with ideas, not people

- Helping is not the same as giving answers

Many of the group norms reiterate the marriage between content and literacy such as “say your because” and “put the question in your answer.”

After the small groups discussed their answers, the teacher jotted down their responses on the board. The conversation with the whole class continued until a student finally responded with “The phone is charging!” From that response, the teacher shifted to the second sentence starter posed to students, “I Wonder…”, in which the students start sharing inferences based on the image. Eventually, a student says, “What time will the phone be charged?”

Solving the Problem

Once students land on this essential question, the lesson then shifts to the “second act” where students attempt to solve the problem. The Math teacher then asks the students to make a “too low, too high, and just right” guess at what time the phone will be charged if it is 5% at 9:02. Asking students to estimate a too high, too low, and just right answer is critical thinking and at the heart of student’s mathematical practice standards. (SCCCR.MP 1-7). In just one sentence, a too high, too low, and just right guess allows students to use reasoning and analysis to create a path to problem solving. After students shared some guesses, the teacher shared three more images, revealing the next three stages of charging.

The teacher then told the class: “Now we are going to represent data. Four representations of math are words, tables, graphs, and equations. Please remember to answer your questions in the form of a sentence.” She also reminded students of one of the group norms: say your becauses. For the math teacher, it is important that students represent Math in all four representations every lesson. This representation of data reiterates the importance of students developing a deeper mathematical knowledge. The students first represented math through words, so they moved onto representing it in a chart.

Before they began developing their charts, the teacher and the class worked together to define their variables for this situation (x=minutes of charging since 9:02; y=battery percentage).

| X | Y |

| 0 8 12 24 | 5 14 19 33 |

After creating the chart, the teacher asked, “using the data in your table, can you determine the type of relationship between these two variables?” The class consensus was that it is a positive relationship and appears nearly linear.

The teacher then told the class, “For now, let’s assume it is nearly linear. If this is true, could we use the data to write an equation to use for prediction when the phone will be fully charged?”

Y = 1.17x + 4.88

100 = 1.17x + 4.88

X ≈ 81.3

Therefore, they determined the phone will be charged approximately 81 minutes after 9:02, or 10:23. After they solve the equation, the teacher then revealed the answer to show the students by slowly showing the progression over time.

The slow reveal built suspense, and ultimately curiosity from the students. As Lent states, “The process of wondering, formulating questions, and thinking through concepts while respecting multiple viewpoints is as much the goal as certitude about a concept” (Lent & Voigt, 2019, p 111). If Math is the aspirin, then teachers must create the headache. Not a migraine, but a “cognitive conflict” or a “disequilibrium” (Meyer, 2015). This headache is created through the processes of wondering, questions, and thinking. And at just the right time, with just the right amount of curiosity and inquiry, the aspirin is given to the students in a sigh of relief (and frustration!).

At this point, the class has represented math in three different ways: words, charts, and equations. The last representation is a graph. After the final reveal, the teacher says to the class, “What happened? We assumed that it would continue charging at the same rate. But as we start charging batteries, it actually gets slower. It starts slowing down.”

The Importance of Disciplinary Literacy and Collaboration

While there may be hesitation for educators to pedagogically shift towards a disciplinary literacy approach to instruction, collaboration and co-teaching narrows the gap. Disciplinary Literacy is not merely reading and writing across the content, but rather placing literacy within the discipline itself. Lent explains, “…While practice is still important, the emphasis has shifted from only teaching the principles of math to helping students develop a deeper mathematical knowledge– and such instruction often includes collaboration” (p 155). I am thankful for Math teachers who take transformative action about the way in which they think about their content. I am thankful for a school where disciplinary literacy is a school-wide initiative. But most of all, I am thankful for literacy itself and its rightful place in all disciplines across all curriculums.

References:

Lent, R. C. (2016). This Is Disciplinary Literacy: Reading Writing, Thinking, and Doing… Content Area by Content Area. Corwin.

Lent, R. C. & Voigt, M. M. (2019). Disciplinary Literacy In Action: How to Create and Sustain a School-wide Culture of Deep Reading, Writing, and Thinking. Corwin.

Meyer, Dan. 2015, 17, June).If Math Is The Aspirin, Then How Do You Create The Headache? Dy/dan. https://blog.mrmeyer.com/2015/if-math-is-the-aspirin-then-how-do-you-create-the-headache/

About the Author

Lindsey Douglas is a Clemson University graduate in English Literature, Secondary Education, and a Masters in Literacy K-12. Lindsey is a third year English teacher and is the 8th grade English Department Head at Gettys Middle School. She is passionate about disciplinary literacy and helping teachers embed literacy practices into their content. She also coaches volleyball and enjoys spending time outdoors, and reading.

About the Collaborator

Ashley Weaver is a National Board Certified Teacher and math nerd with 13 years of experience teaching middle schoolers. She teaches with the belief that all students can learn math and achieve at high levels and hopes to instill a love for learning in her students. When she isn’t teaching or learning about teaching, she enjoys reading and spending time with her husband and daughter.

By: Shanna Towery, South Carolina ELA Teacher

Greeting a classroom full of students and then closing out the rest of the school world with a firmly shut door seems to be the norm for many classroom teachers today. The autonomy afforded to teachers has its benefits, but it can also be detrimental to the mental health of teachers as well as the overall culture of a school.

What’s Wrong with Collaboration?

It would be hard to pinpoint exactly what is to blame for the general ill-will often felt by educators towards collaboration or the dreaded PLC. Maybe it’s the sense of competition garnered from high-stakes testing or the half-hearted attempts at professional development where many teachers are sure to be found half-listening with a stack of ungraded papers. Whatever the cause, the real casualties when collaboration is not fostered, encouraged, and celebrated are the ones who need it the most–our students.

Collaboration: For the Students or For the Students?

Most teachers would agree that students are social creatures. As such, we can utilize their tendencies for communication through class discussion, turn-and-talk strategies, or collaborative groups as effective teaching tools. In this sense, educators are encouraged to use collaboration among students to foster learning in the classroom, but are teachers as willing to collaborate together to ensure every student truly learns? How often do teachers meet in your building to use real classroom data to authentically discuss student progress, successes, needs, for enrichment?

For too many schools, the answer to these inquiries would be disappointing to advocates for professional collaboration. Why is it that collaboration among students in the classroom is a non-negotiable, while the adults in the building do their best to cling to their autonomy? When did we outgrow communication as a means to deepen and build mutual understanding? How can we be so willing to participate in discussion forums, Facebook groups, book clubs, or Bible studies, but hesitate to collaborate with the colleagues in our buildings? And most importantly, what can we do to turn this around?

PLC: More Than Meets the Eye

Professional Learning Communities have gotten a bad rep thanks to half-hearted attempts done simply to check a proverbial box. In reality, PLCs have so much more potential and value when utilized correctly. While book studies and grade level/department level meetings are important and definitely have their place in a positive school climate, the kind of PLCs I have found success with are more about student achievement than they are teacher-centered. In this type of PLC, teachers would meet together prior to teaching to discuss learning goals and objectives. The teachers would not discuss activities or lesson plans so much as they would discuss what they truly wanted their students to gain from upcoming lessons. Only when the goals have been identified would teachers discuss how best to teach for the goals as well as how they would know whether or not the goals had been met (think: assessments). After teaching, the teachers would gather the data from the classroom assessments and meet again to compare notes and discuss patterns, ahas, or concerns. A step often missed here is what to do next–will re-teaching be necessary? Is there room for enrichment? And with true Professional Learning Communities, the cycle would then begin again!

Literacy coaches will recognize what I have described as student-centered coaching cycles (Sweeney, 2011), but as evidenced by a professional development session I was privileged to attend with select members of my district through Solution Tree, this type of PLC has various formats and can take place with or without a literacy coach. Ideally, proper school leadership would encourage this type of student-centered learning approach throughout the building, but all it takes is a few teachers willing to work through a few cycles for it to catch on. As a 6th grade ELA teacher, I was able to conduct a few cycles with a 7th grade social studies teacher last spring before school ended abruptly to offer some insight to her regarding disciplinary literacy. We put our individual expertise together to determine goals for “reading” primary documents and then analyzed data together to inform her teaching. I was able to help her create a rubric for assessment based on our goals and it became very clear through this process what students were understanding and what needed to be re-taught or further scaffolded. It was such a refreshing and rewarding experience to feel that we were collaborating in a way that would truly be useful to both teaching and student learning! Afterwards, I was able to carry the type of work we had done into my grade level ELA planning meetings.

A Call to Action

After years of thinking I knew all there was to know about PLCs and professional development, I found this reimagining of the student-centered PLC to be just the kind of collaboration I could get behind. My hope is that others will see how incredibly beneficial collaboration can be when professionals are willing to meet together on behalf of their students in a non-judgemental or threatening way. Our students deserve it!

Sweeney, D. (2011). Students-centered coaching: A guide for K-8 coaches and principals. Corwin

About the Author

Shanna Towery has sixteen years teaching experience across a total of four school districts in South Carolina. She is a recent M.Ed. graduate from Clemson University and is currently a 6th grade ELA teacher.

By: Victoria Young, a South Carolina Teacher

When I began teaching virtually this school year, I was excited to utilize all of the technological resources and techniques I learned in university that I hadn’t had the chance to try out. However, as most teachers know, it is almost impossible to effectively teach content in a meaningful way to kids when they are unable to connect with the content and one another. In the virtual classroom, students are unable to simply turn to their neighbor and discuss a problem or quickly whisper questions and comments to one another in class. Sure, no teacher will deny the fact that the mute button is a game changer for classroom management, but they will agree that it does damage the classroom community. The social barrier created by virtual learning seemed to put the important skill of collaboration on hold for this generation of students. So how do we as teachers reignite this connectivity in the virtual classroom?

Tip #1: Build confidence with anonymity

For me, it was a long process filled with patience. The first day of school is always awkward; but with technical difficulties and lack of participation, the first day shyness lasted the first two weeks. The way I approached a lack of classroom engagement was by treating virtual classes like a shy kid. You know the one – shoulders hunched, little eye contact, and always chooses to do the group assignment alone without asking. With tools such as Nearpod, Polleverywhere, and Google Forms, I did activities in and out of class that allowed students to express themselves and their thoughts and opinions with anonymity. As a class, we would see how we all think alike or learn new perspectives. I would ask for opinions on silly things like what I should eat for lunch for kids who are more outgoing to speak up without pressure of being ‘wrong’. When the more outgoing kids started to lead the way with the easy interactions, I saw that even the quieter students begin to speak up in the chat or even unmute! Eventually, through these distant interactions, I noticed more and more students interacting in class in day to day conversations and in content related discussions. They began to gain confidence once they saw that they are safe to share their ideas.

Tip #2: Use mainstream tools to your advantage

Once we broke the 10 layers of ice, I began to do more collaboration boards and Flipgrids without anonymity in order to encourage more discussion in class. In my very social classes, I have even gone on to do partner projects through remote learning. Middle and high school students are on every type of social media; so many of my students chatted via Snapchat, Instagram, and even Discord. Other students with less access to social media simply communicated via email. All that to say, students are collaborating all the time, we just have to use their methods to our advantage! (If you can’t beat them, join them!) I was never given any issues with participation despite how different this form of collaboration is and how it appears more arduous than simply sitting next to a partner in class. It is as if the ability to collaborate without a teacher facilitating every step was freeing; therefore, I began to see their personalities shine through their work.

Tip #3: Find common ground

Of course, not every class can achieve the same level of collaboration in the virtual world. That doesn’t mean, however, that it can’t be achieved! One of my classes’ favorite activities is to play Among Us as review before an assessment. While talking about our weekend plans, I told my students I was going to play video games with some friends. This built a quick connection between me and my classes. Eureka! We finally had something in common besides being stuck in quarantine. On Gimkit.com, there is an activity that allows students to review material while playing in a similar format of the popular game Among Us. Students get very competitive and have to interrogate one another in order to win. There are also several other games that allow collaboration; but I always start with a solo game to help students get used to the mechanics. Nothing says virtual like video games and they are a great way to build community and collaborate in order to learn!

No matter the grade level or content you teach, collaboration is achievable in your classroom whether you are in person or online (or both!) this school year. Remember that at the end of the day, the goal of collaboration is to build relationships and problem solving skills. If you notice that your student collaboration is lacking in the qualitative results you want in your content, try to treat it more as a social skill. If you nurture your classroom’s environment first with collaboration, the learning will come along with it. Find a common interest, talk to a child or teen about what they like to do in their free time, and use those things to your advantage! Take away the fear of failure and show that you are all just as human as each other and soon your students will see that learning can be found all around us, not just in a school or textbook. And isn’t that the most powerful lesson that we can teach?

About the Author

Victoria Young, B.A. Secondary Education/Social Studies, is a geography and world history teacher at Greenville Technical Charter High School in South Carolina.

By: Charlene Aldrich, retired South Carolina Literacy Instructor

In education, there are times when it’s a little bit of both. I like to believe that Better Together overcomes Misery so that Company discovers possibilities rather than ponders problems.

Too often educators, unknowingly, develop a silo mindset in their quest to accomplish everything that needs to be done to meet everyone’s needs – the state, the district, the administrators, the students, the parents, and the support staff members. It’s a gradual process and, unlike the business definition of a silo mindset, is a re-action rather than a pro-action. A silo mindset in business develops when co-workers refuse to work together as a team – hoarding resources and hiding ideas that benefit the whole. Personal recognition trumps the greater good. Fear of losing out overshadows building relationships.

In education, however, silo mindsets develop in response to overwhelming workloads, little downtime, and too much paperwork! It becomes easy to say, ‘I don’t have time to collaborate,’ and ‘I just want to get home.’ There’s not even time to contemplate the fact that ‘better together’ results in efficient and effective instruction as well as developing a support network. I’d like to suggest three ways to promote collaboration in a school: grade level, content area, and schoolwide.

Intradisciplinary Collaboration

Intradisciplinary collaboration within a school is big picture collaboration; it involves planning curriculum that has continuity, scope, and sequence from an intro course to the AP offering. Long-term planning such as this happens outside of the regular school year. The biology team or the Algebra team or the Honors ELA team meets at least two times a year: one to look back and one to look forward. Another model is a two-day retreat with the same idea – looking back and looking forward. Priorities include sequenced content area text resources, scaffolded instruction from course to course, and intentional development of disciplinary literacy practices. Collaboration between teachers who teach the same courses should focus on dissecting the course standards into individual lessons to develop content area knowledge necessary to meet them.

Grade Level Collaboration

Grade level collaboration, on the other hand, is an ongoing effort among colleagues to develop ways to build relationships between the content of each other’s courses. In an effort to provide real world connections and context for learning, teachers work together to plan content overlap that is mutually reinforcing. Literature pairs well with history; mathematics pairs well with business and economics. The arts curriculum overlaps with history as artists’ and musicians’ compositions reflect the culture in which they were created. Lyrics in music correlate to poetry in ELA. Sciences and math are mutually reinforcing; construction trades, culinary, and physical education include math calculations, conversions, and statistics. And every content area has significant people whose lives are told through biographies and autobiographies which are just one of the many categories of literature taught by ELA teachers.

Collaborating across a grade level doesn’t even have to be synchronous to be effective. Connected content introduced in one discipline becomes background knowledge in preparation for future content of another discipline; it also serves as a source for applying content knowledge to new learning situations. Long term retention is accomplished as connected content surfaces a variety of courses that review, connect, and extend content for deep understanding.

Synchronous School-wide Collaboration

Synchronous school-wide collaboration is possible several times a year in response to awkward calendar planning. For example, the day of Halloween and the day after Halloween are sometimes void of learning because excitement replaces focus. Thematic collaboration on these isolated days rescue students and teachers from wasted time and potential behavior management issues. Two days of hype and sugar-highs are replaced with inquiry and fact-finding: history, cultural celebrations, economic impact, spending statistics, chemistry, nutrition, poetry, drama, short stories, music, art, and even physical education! All it takes is a little creativity mixed with a lot of enthusiasm to connect content, include a course requirement, and engage students throughout the school around a common theme two or three times a year. I can personally recommend this NewsELA article as a place to begin:

https://newsela.com/read/halloween-spending/id/46288/?utm_source=email&utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=web (It will ask you to make an account to read the article; the article as well as all of their ‘news’ articles are free. Other content needs a subscription. All of their free news articles make great themes for collaboration or connecting to specific lessons in your content area.)

What are the ‘down days’ at your school? There should never be a class day that a student can say, ‘It’s Halloween. The teachers never do anything important on Halloween. I can stay home.’ If you are reading this, then you may be the one who can make collaboration happen in your school! Find the First Follower in YOUR school and do it!

About the Author

After 20 years of growing literacy in under-prepared college students, Charlene retired to focus on state-wide literacy initiatives such as LiD, 6-12 and her R2S approved literacy courses at College of Charleston. She lets her life speak by empowering teachers to have the confidence and competence to implement a literacy model of instruction in any content area and at every grade level. Her best Covid-19 memory is teaching her grandson Algebra 1 via phone calls, Zoom, text messaging, and FaceTime. It was online instruction at its best – synchronously and interactively.

Literacy Coaching During A Pandemic

By: Meagan Wagner, South Carolina Middle/High School Teacher

Coloring pages. That’s what it took, this week, to motivate my eighth grade boys’ book club to read their assigned pages in the novel. Donuts weren’t appealing and candy is lackluster after Halloween. Yes, I bribe students with goodies. Or, in educator-speak, I provide extrinsic motivation for my students. And if you thought coloring pages would be too elementary for teenagers, then you’d be wrong. I am their literacy coach – and they do not receive a grade from me, so creativity is required to engage and motivate. In fact, that last statement pretty much sums up what it is like to be a literacy coach during a pandemic.

In a normal, non-COVID-19 school year, being a literacy coach means fulfilling many duties. Organizer of novel sets. Assessor of reading fluency and comprehension. Analyzer of standardized testing data. Listener to teacher meltdowns. Bulletin board decorator. Book pusher. My daily role also consists of working within English language arts classrooms as a co-teacher of sorts, pulling struggling readers for reading strategy conferences, conducting walkthrough observations in classrooms, and designing/facilitating professional development opportunities for my faculty. This is not that sort of year.

COVID-19 presented unique parameters within my rural school district. First, the last time we saw our students was six months prior to when they returned to buildings on a new alternating-day hybrid schedule. Second, we were quickly distributing devices to students for the first time ever, because our schools were adamantly NOT one-to-one with computers. Third, many families chose our district-provided virtual option. In an English language arts (ELA) class that would normally consist of twenty-eight students, and would benefit from my co-teaching assistance, we might have eight students on a strong attendance day; most days are not strong attendance days. Fourth, my colleagues are balancing the workload like never before: creating in-class lessons that are not allowed to include group work, providing additional work for the students’ at-home days, providing quarantine packets for students sent home, all while learning new technology.

Making Collaborative Adjustments for COVID-19

I knew before walking into the building in August, that this was not the time to be a normal literacy coach. Co-teaching in a group of eight or less might not be the best use of my time. Conducting walkthroughs to identify instructional needs is NOT a good idea right now — this is not a normal instructional year. Professional development opportunities on incorporating literacy into the content areas is obviously not a priority. This does not mean that my role is not important or valuable for teachers during this time. Creativity is required to engage and motivate teachers AND students.

Coaching Priority #1 – Determine the Best way to support the teachers.

In the same way that we differentiate for students, we should differentiate for teachers. My sixth grade teachers wanted help with grammar: so weekly lessons from me are a go. My seventh and eighth grade teachers wanted to be able to reserve times with me instead of having an assigned visit per week because, too often, my assigned time in their class was filled with helping students who came back from quarantine, or organizing a messy student’s binder.

While these activities have their merit, it was not the best use of my time. Therefore, I created a Google Doc schedule and shared it with my department. This engaged and motivated my teachers to use me in new ways. They have booked me for stations and review lessons, re-teaching small groups, book clubs, and read alouds. As a department, we saw a need to help students learn how to pick out books that are good choices for them. A series of stations and book talks ensued. My high school teachers wanted help furthering independent reading interest for students they only see in person twice a week. I began booktalk videos and trailers that they could provide via technology.

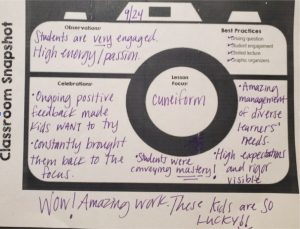

Coaching Priority #2 – Be the voice of encouragement

Teachers, not just in English language arts, were reporting burnout and lack of encouragement. I began walkthrough snapshots — as a means to celebrate the amazing adjustments seen in classrooms. I visit the room, take photos with permission, and leave a note for the teacher that lists all the positives I saw happening. Feedback suggested that teachers want to show off the ways they are adjusting — and rightly so. They are doing amazing things with technology, social distancing, and keeping themselves safe all the while. I have since seen my snapshot celebration forms hanging above teacher desks.

Every stakeholder in education has made major changes to adjust to COVID-19. Administrators, parents, students, teachers, coaches, secretaries, media specialists, custodians, and so many more. The fact that we have managed to rise to the occasion is something to be celebrated and to unite us. We are all in this together and we will do whatever it takes — even if that means printing coloring pages.

About the Author:

Meagan Wagner, M.Ed., NBCT, is a literacy coach for middle and high school in South Carolina. She is also a doctoral candidate at the University of South Carolina, in Curriculum & Instruction.

By: Dr. Jennifer D. Morrison

In 2016, the University of South Carolina Language & Literacy faculty members decided to overhaul the Masters in Education degree requirements. The then current program was outdated and focused on very narrow conceptions of literacy, who owned it, and how it was to be taught. Because we all hailed from strong critical theory backgrounds, we knew a social justice thread was imperative. Through this lens, as we examined individual courses as well as the program as a whole, we began to ask questions such as: who owns literacy? How do we want to present this? What about funds of knowledge and out-of-school literacies? This line of questioning led us to realize that nowhere in our program did we account for parental and community involvement in students’ literacy learning. This, to us, was a huge gap that needed to be filled. We decided to redesign a course entitled “Guiding the Reading Program,” changing it from a third assessment course to one on literacy leadership with a focus on developing skills that would assist teachers in employing community and family resources in school and district literacy practices and policies. I was the initial instructor for this course and looked to my experiences, as an instructional coach and administrative intern, to help me build the curriculum and key assessment experiences.

Tough Conversations and Deep Reflection

When discussing family involvement, it is not uncommon to hear educators talk about how many parents attend PTSA meetings, come to Open House/Curriculum Nights, or support the band/athletic boosters. However, it becomes important to really consider which parents are involved and what percentage of the school they represent. It is often eye-opening to realize large swaths of families are un- or under-represented at school events. For example, as the instructional specialist at a middle school in Maryland, I was part of a school leadership team who specifically sought to broaden our parent involvement, not only in how they were involved but also in who was involved. We had a very active and invested community; so, when we collected data about who was coming into our school for social and academic activities and who was not, it was surprising to see we had almost no members of our Latino families represented. This required us to conduct deep reflection and address cultural divides. We thought we were providing appropriate communication with our families by sending home notices in backpacks and posting on our school’s social media and websites. However, when we asked members of the Latino community why we had limited attendance, they indicated to us more personal means of communication were needed. When we started picking up the phone and personally calling families, we found they were significantly more responsive; we had to bridge a cultural divide we did not realize we had built, to ensure all families felt welcome. This is not an uncommon experience that emerges once school leadership teams and teachers delve mindfully, deeply, and honestly into the degree to which families and community members are truly involved in schools.

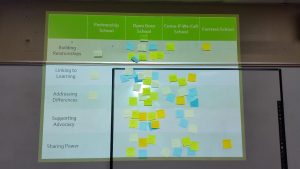

The Work

In my class, one of the early activities I ask teachers to complete is a pair of inventories regarding parental involvement practices. The first is Salinas, Epstein, and Sanders’s (2012) An Inventory of Present Practices of School, Family, and Community Partnerships. It identifies six ways parents can be involved in schools (called “types” in this instrument) including: parenting, communicating, volunteering, home-learning, decision-making/leadership, and community collaboration. School members are asked to consider the degree to which statements listed under each type are true and in what grade levels. These responses help illuminate both traditional and nontraditional means of involvement and also show if there are patterns or trends in participation. I then pair this inventory with a second evaluation instrument from Beyond the Bake Sale (Henderson, Mapp, Johnson & Davies, 2007). This instrument uses five domains (building relationships, linking to learning, addressing differences, supporting advocacy, and sharing power) to help educators identify which of four versions of family-school partnerships best describes their school (partnership, open-door, come-if-we-call, or fortress). To help them to see patterns, I ask students to identify which version of partnerships their schools represent for each domain and place a sticky note in the appropriate location (see Figure 1). While most people would say they have a partnership school, especially at the elementary level, many individuals are surprised with the results of this survey. There are areas suggested, such as including parents in curricular decisions, many of my students have not ever considered.

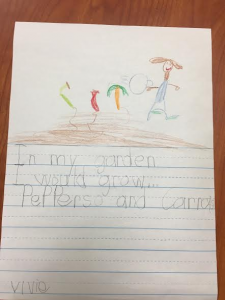

Between these two instruments, my students begin to get a clearer, and more accurate, picture of their schools’ strengths and needs with regard to parent and community partnerships. They are then asked to develop a family and community partnership grounded in the data they have collected from these two sources. I encourage them to think about how they can move their school to a higher version within one domain of the Beyond the Bake Sale rubric while also using some of the descriptors from the Epstein inventory to help frame goals and action steps. The projects that have emerged from this project have been organic, deeply-embedded in individual school needs, centered on literacy, and overall impactful. One resulting project was discussed in this blog by Hannah Kottraba in June when she wrote about her family heritage project. Other examples have included virtual science activities where parents and students engage in disciplinary literacy to solve scientific problems; pre-k students engaging in pen pal writing and subsequently building a garden with members of an assisted care facility (see Figure 2); online interactive math resources (focused on literacy needed for word problems); workshops that coach family members how to support reading with all ages of students; family culture exhibits; writers’ gallery celebrations; and international student shadowing days where high school students serve as hosts for international graduate students learning about America’s education system. Many of these projects addressed family and community populations who are often underrepresented in schools, and several have become multi-year or ongoing events.

It is important to remember that such projects are many times singletons, snapshots that occur once as a result of a course; the impetus being the need to complete a class assignment. I am not so naïve as to think these class assignments have suddenly made every school my students teach at a Partnership School. What is important is the paradigm shift that occurs as teachers undergo this process. They begin to seek out ways to better meet the criteria established by these two inventories; they become more attuned to cultural differences that may be acting as a barrier to some families and making them feel unwelcome with the school space; and they become more appreciative of the funds of knowledge parents and family members bring with them.

About the Author

Dr. Jennifer D. Morrison is an instructor at the University of South Carolina. Her experiences include being a middle and high school English teacher, gifted education resource teacher, and instructional coach. She earned her Ph.D. at the University of Nevada, Reno, in Language, Literacy, and Culture. She is a National Board Certified Teacher (AYA/ELA), an alumnus of the Teaching Shakespeare Institute at the Folger Theater in Washington, D.C., and has won multiple awards for teaching and writing including NCTE’s Paul and Kate Farmer English Journal Award and AERA’s Dissertation Award in Research on Teacher Induction. Currently, her research focuses on adolescent, digital, multimodal, and disciplinary literacies as well as narrative and qualitative methodologies.