By: Elinor Lister, Glenview Middle School English Teacher

One year at the start of the school year, a student asked “Do I really have to read and write?” I think my response was “Umm, yes, this is English class.” I’ve also answered this sort of question before with something like, “No! Not at all. This is only school. We don’t do those things too much here.” My sarcasm is definitely why I teach eighth grade and above!

Many children would rather do anything else besides read and write. So many of the rules and regulations of our education system have beaten the love of either out of them.

– Elinor lister

Despite the humor and our eye rolls at these questions, lies a real truth – one that is disappointing and frightening. Many children would rather do anything else besides read and write. So many of the rules and regulations of our education system have beaten the love of either out of them. Teachers have to prepare students for benchmarks, MAP testing, SLO tests, standardized tests, etc. To do this, we often give students things to read that we wouldn’t want to sit down and read ourselves, if we didn’t have to do so. We make them write nothing but what will help them answer a discussion question well or respond to a writing prompt correctly. All of these expectations have removed the one thing that is vital to a student truly receiving a good education – the desire to learn.

As educators it is our job to handle the mandates and requirements of assessments while finding ways to help students want to learn, love to read, and desire to write. Piece of cake, right? As easy as putting out a house fire with a water bottle! And yet, teachers do it every day because they are awesome and dedicated and refuse to stop trying.

In my career, I have run across some tools that I have used or seen used with success in helping students enjoy reading and writing. Most of these transcend content and can be great practice in any classroom.

Tools to Increase Student Enjoyment of Reading and Writing

Sustained Silent Reading (SSR)

This isn’t new, but it has fallen by the wayside. I know the argument some use saying that students sit there staring at a book and do not actually read. There may always be a few who are harder to reach than others, but don’t take the experience away from the majority.

Colleagues and I have found the best success with SSR when students can truly pick what they want to read – books, magazines, graphic novels, newspapers, informational texts, etc. I’ve even allowed children’s books. Does it really matter what they are reading, if they are interested in reading it? I never found success forcing students to keep a reading log or write about what they read each day. We should give them time to read what they want to read. Let them rediscover the joy in reading, and learn that reading doesn’t have to have strings attached to it. As adults, we read because we want to and because it’s entertaining or informative. Why can’t students experience that too?

Hyperdocs

These documents are a wonderful way to pull a variety of literacies together for one topic. A hyperdoc moves students through their work, it can take them to different articles, videos, images, and websites. Students read and process through so many varying texts to learn, analyze, and produce results. Hyperdocs are a fantastic way to engage students while having them read, write, think, and produce. If you are unfamiliar with the term, Google it, and you will find so many examples and help guides. You’ll be glad you did! I use some form of a hyperdoc now for almost every unit.

Current Sites

Current. Relevant. Now. Typical curriculums rarely involve reading this type of work. There is amazing and interesting literature out there to be read, enjoyed, and used in classrooms. I am not suggesting we get rid of pieces that have age, history, or formality to them, but those are primarily taught in English classes. English classes don’t need to be the only classes reading, and English classes can certainly bring in some current reading as well now and then. Teachers don’t need to spend their valuable time searching for material, though. There are several sites that have wonderful articles and materials that span various contents, themes, topics, and reading levels.

- Actively Learn has a wealth of articles with guiding questions and discussions to accompany each one. The questions and discussions are also editable so teachers can make them exactly what they want, if needed. This site has had so many wonderful articles throughout Covid-19 that spoke directly to students’ fears, uncertainties, and stresses. This site is completely free.

- Newsela also has a wealth of current and relevant articles. It has articles based on primary and secondary sources, on topics such as art, money, sports, health, etc., and on speeches and famous people. Each article has a quiz relating to the content of the article that can or cannot be used along with a writing piece. What I love is that the writing prompt can be edited to fit what the teacher wants to focus on for discussion. There is a free version to this site that offers a great deal, but it has some limitations.

- TeenInk is another site. This site has pieces that have been written by teens themselves. It has writing in magazine form, fiction, poetry, nonfiction, reviews, art and photos, and more. There are so many genres offered within each of these categories, even the most reluctant reader can find something. They are very real and very relevant. Those interested can also create an account and submit their own writing to be published on the site. After reading pieces by other teens, many want to write themselves and submit their writing for publication.

Blogs

Students have to learn to complete academic writing. They need that knowledge for all parts of school from upper elementary through college. In teaching that, however, we often forget that students need to experience freedom in writing. It is creative, therapeutic, and enlightening. We can learn so much about our students from their writing, but we rarely feel that we can allow them this time. A way I find to give them this opportunity is through blogs. I set up a Google Site (either with multiple pages or with embedded Docs) and allow students to make it their own. They can write about anything on their mind or any topic they are interested in; they just have to write. I try to give them twenty minutes two to three times per week. I have ninety minute classes, so that works for me.

I have had students write about recipes, makeup tips, sports, extra-curricular activities, traveling, hobbies, friends, drama, dating, video games, etc. They can add pictures, videos, you name it. You can also have blogs that are specific to topics so that students write about content but in a less formal way. This could be books they’re reading, reviews of things, or thoughts on characters or chapters. Blogs would work in any content area, and they are a real-world type of writing that allows students to feel heard in their own way, not through a formal essay.

Student Choice

I firmly believe that one of the greatest ways to utilize students’ strengths and make learning relevant is in allowing students to have choice. It could be choice in a topic, choice in a project medium, choice in a partner, anything – just give them choice. Let them take ownership! Students can learn information and be able to share that they have mastered it in so many different ways. Capitalize on that. As teachers, we often get worried about giving away control. Our control doesn’t often create engagement and expand student literacy. Set up parameters, give guidelines, create a rubric, and let students go. You will be amazed at what they can create!

Allow students to write books with Slides, Forms, or websites like Storyjumper. Let them create a comic strip with a website like Pixton. Give them the freedom to write a script and film a video. Provide a topic to research and tell them to present that information in any form such as a Prezi or a Powtoon to so many other websites that are free and available. Here’s a short list of some favorites: Adobe Spark, Canva, Smore, TES, Padlet, Flipgrid, Screencastify, Thinglink, and Emaze. I even have a colleague who walked students through scientific research and then let them create podcasts! They were fantastic.

Our students live in a world of constant technology. They are immersed in it. We need to let that spur them into renewing their reading and their writing.

We have so many tools at our disposal, so many ways to enrich our students’ literary skills. They live in a world of technology; it is all around them. We can use that to our benefit to help renew their desire to read and write. We can also remind them that reading and writing should be more important to them than just fulfilling academic requirements. Once we can hook them, the academic success will follow.

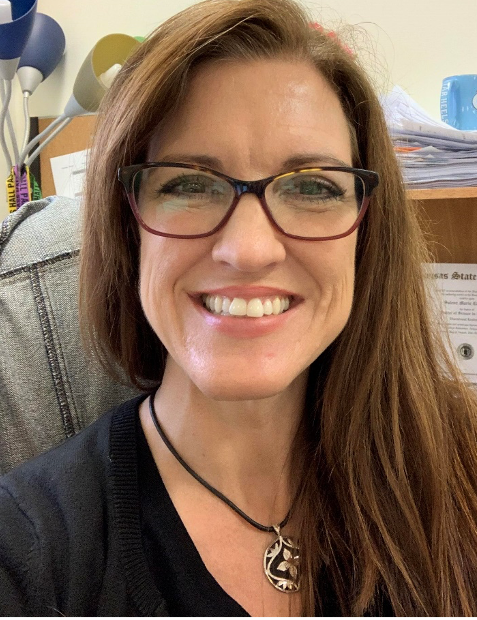

About the Author

Elinor Lister has taught high school and middle school English for twenty years and currently teaches eighth grade English in Anderson, South Carolina, at Glenview Middle School. She was the District Teacher of the Year for Anderson Five for the 2018-2019 school year. Elinor holds a Bachelor’s in English from Erskine College, a Master’s in Educational Technology from Lesley University, and a Master’s in Administration from Gardner Webb University.