By: Kathleen Pennyway, High School Drama Teacher

Before the schools closed…

My classroom was fully invested in the practice of trauma-informed teaching. I was confident in my ability to build relationships with students that were based on honesty, listening, and mutual respect. I used those relationships to strengthen my students’ academic and social-emotional abilities. We had regular meditation practice in my room for all of my students. I had a couch in the corner that students frequently used to calm down if they needed to decompress from a stressful situation, and snacks in my office if anyone had forgotten breakfast. There were signs in my room celebrating diversity and respect for all, and my students regularly had conversations about race, police brutality, sexism, gender and sexuality, and other issues of social justice. I had agreements with other teachers in the school that if they needed a student to cool down for a second, they could send that student to me. Each of these strategies was designed to center my students’ needs, and to help them to deal with traumas such as violence, home instability, and poverty.

My students frequently commented the drama room was the place they felt safe, and I wore that accolade with as much honor as the awards we won at state competition. And there were many teachers at my school who were doing these things – I was only one part of a committed group of teachers who were working towards trauma-informed practice as our goal. Our school was making leaps forward, with plans for student and teacher wellness rooms, a good amount of teacher buy-in, and successful professional development opportunities. In short, there was momentum building in trauma-informed practice.

And then, the virus charged through our country and ripped apart everything that we had built.

I don’t know that I have ever felt as lost as an educator as I have during the past six weeks. I felt I was working harder than I have ever worked, and simultaneously I was failing at my job in reaching students. There were many times when I felt like giving up in despair. But I didn’t. As educators, our mantra is monitor and adjust, so I did. I made many mistakes over the course of learning how to teach theatre virtually, but I believe I have arrived back where I belong, with trauma-informed practice at the center of my teaching.

Here’s what I have learned.

1. Keep relationships at the center of your job

In the normal world, my classroom is constantly filled with of young people. From before the first bell rings, to long after everyone else in the building has left, there is theatre happening in Room 133. But more than that, I have worked hard to make the drama room a space where my students feel comfortable and safe. Whether kids needed a nap on my futon, a minute in the costume closet to cool down, or a chat in my office, they came to the drama room to find it.

Part of trauma-informed practice is creating a physical space that helps students relax and be able to learn. The loss of the physical space of my room left me without a huge tool to check in on students who are struggling academically and emotionally. The relationships built in school are grounded in the physical space of our classrooms. In a COVID-19 world, reduced to Zoom meetings and virtual assignments, our ability to connect and build relationships suffered. One of the things I miss the most about school is the ability to connect with my students easily and naturally on a human level. To say “Hey, I read that book you told me about,” or “What did you think of this scene in a play?” or “Have you heard about the new video game?” and hear about their interests and their dreams and who they are as people.

As online teachers, we need to be more intentional than ever in our efforts to build and maintain relationships with our students. Some of the things I did to maintain those relationships included starting weekly Instagram posts where I would pose a silly theatre related question that students could respond to. I hosted watch parties of plays on Zoom and virtual “lunches” in the drama room. And I started reserving time in our Zoom classes to ask my kids to share things that were going on with them – what they were watching (a lot of Tiger King), whether they missed school (surprisingly yes) and whether they were sleeping on a normal schedule (definitely not). These non-academic pursuits brought back several of the students who had gone no-contact, and I was able to use them to convince some of those same students to complete some of their academic work.

It is easy, in the world of eLearning, to reduce a teacher’s job to academics. This is a trap, and we dare not fall prey to it. For many of our students, we are a stable and welcome presence in their lives they may not find at home. This presence is as valuable as the content we teach. I know many of us are worried about test scores, the summer slump, AP Exams and college preparedness. I understand this worry, but it cannot take precedence over our relationships with our students.

2. Encourage self-care in your students, and practice it yourself

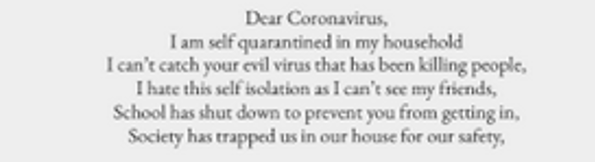

Students and teachers alike are experiencing some sense of anxiety, loss, grief or trauma right now. The news of the virus alone is enough to keep anyone awake at night. Many of our students are experiencing economic hardship due to the pandemic as well. And there are losses that are small to adults but loom huge in the lives of our students. Prom. Graduation. Spring performances.

These are losses and your students deserve to grieve them. When a student tells me about something they are upset about, I don’t placate or tell them there are people who are worse off. I don’t tell them they shouldn’t feel the way they feel. Learning to recognize and regulate our feelings is an important part of trauma-informed practice. I frequently tell my students feelings are never right or wrong, and controlling what we do with our feelings is more important than the feelings themselves.

At the same time, we need to make certain we are practicing what we preach. As I mentioned earlier, I had an extremely difficult adjustment to eLearning. There were times when no matter how hard I struggled, I barely felt like a teacher. In addition, I was caring for a 5-year-old and a 2-year-old who were also experiencing some regression due to the pandemic. My spouse and I were both working from home, and there were many days where I felt like a failure as both a teacher and a mother.

I eventually came to the realization that I was allowing my students flexibility that I did not allow myself. I needed to make changes – adjusting my Zoom schedule to coincide with my younger child’s nap schedule, for example, or creating time to do yoga and work in my garden. Many teachers have strong senses of empathy, and teachers who work with students who are dealing with trauma can suffer from secondary-PTSD. In addition, many teacher families are dealing with the same stressors that our students are dealing with. It is important to build routines of self-care so that we can maintain the emotional stamina to help our students. Our students deserve no less than our very best effort, and we cannot give them our best if we do not take care of ourselves.

3. Create hope, and involve students in a plan for the future

My students have many questions I cannot answer. Will we go back to school in the fall? Will we be able to do a musical? Will we be able to perform next year? It hurts my heart to have to tell them I don’t know. All students, but particularly students who have experienced trauma, need routine and structure to feel safe. So many of our routines are gone now. Nonetheless, I respect them too much to lie to them and promise them everything is going to be okay.

I cannot tell my students what the future holds, but I can give them some control over some of their circumstances. My student leadership board is currently in the process of choosing scripts for next year, as well as coming up with alternate plans in case the virus decides to make a resurgence. Young people are capable of coming up with those plans, and they deserve to have a seat at the table when those decisions are being made. There is very little we can control at this point in time, but offering our students the chance to help plan our future is one way we can give them some measure of certainty and agency. COVID-19 has transformed our reality in a matter of months, but one thing that has not changed is that we as teachers must put our students at the center of our practice. Whether we teach in classrooms or in packets or through Zoom, we can use trauma-informed strategies such as relationship building, self-care, and student-centered processes to better serve our students and ourselves as teachers.

About the Author

Kathleen Pennyway has been a professional drama educator, actor, and director for the past thirteen years, working for such organizations as the Windy City Players, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Childsplay. She has taught and performed in nine different states and worked with hundreds of young people. Ms. Pennyway graduated with a BA in Theatre from Northwestern University, and received her MFA in Theatre for Youth from Arizona State University. She currently teaches theatre at Dreher High School, and lives in Lexington with her husband Dee, her children, Harrison and Rosie, and her dog, Lily.