By: Dr. Jennifer D. Morrison

In 2016, the University of South Carolina Language & Literacy faculty members decided to overhaul the Masters in Education degree requirements. The then current program was outdated and focused on very narrow conceptions of literacy, who owned it, and how it was to be taught. Because we all hailed from strong critical theory backgrounds, we knew a social justice thread was imperative. Through this lens, as we examined individual courses as well as the program as a whole, we began to ask questions such as: who owns literacy? How do we want to present this? What about funds of knowledge and out-of-school literacies? This line of questioning led us to realize that nowhere in our program did we account for parental and community involvement in students’ literacy learning. This, to us, was a huge gap that needed to be filled. We decided to redesign a course entitled “Guiding the Reading Program,” changing it from a third assessment course to one on literacy leadership with a focus on developing skills that would assist teachers in employing community and family resources in school and district literacy practices and policies. I was the initial instructor for this course and looked to my experiences, as an instructional coach and administrative intern, to help me build the curriculum and key assessment experiences.

Tough Conversations and Deep Reflection

When discussing family involvement, it is not uncommon to hear educators talk about how many parents attend PTSA meetings, come to Open House/Curriculum Nights, or support the band/athletic boosters. However, it becomes important to really consider which parents are involved and what percentage of the school they represent. It is often eye-opening to realize large swaths of families are un- or under-represented at school events. For example, as the instructional specialist at a middle school in Maryland, I was part of a school leadership team who specifically sought to broaden our parent involvement, not only in how they were involved but also in who was involved. We had a very active and invested community; so, when we collected data about who was coming into our school for social and academic activities and who was not, it was surprising to see we had almost no members of our Latino families represented. This required us to conduct deep reflection and address cultural divides. We thought we were providing appropriate communication with our families by sending home notices in backpacks and posting on our school’s social media and websites. However, when we asked members of the Latino community why we had limited attendance, they indicated to us more personal means of communication were needed. When we started picking up the phone and personally calling families, we found they were significantly more responsive; we had to bridge a cultural divide we did not realize we had built, to ensure all families felt welcome. This is not an uncommon experience that emerges once school leadership teams and teachers delve mindfully, deeply, and honestly into the degree to which families and community members are truly involved in schools.

The Work

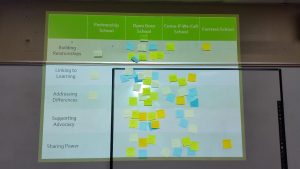

In my class, one of the early activities I ask teachers to complete is a pair of inventories regarding parental involvement practices. The first is Salinas, Epstein, and Sanders’s (2012) An Inventory of Present Practices of School, Family, and Community Partnerships. It identifies six ways parents can be involved in schools (called “types” in this instrument) including: parenting, communicating, volunteering, home-learning, decision-making/leadership, and community collaboration. School members are asked to consider the degree to which statements listed under each type are true and in what grade levels. These responses help illuminate both traditional and nontraditional means of involvement and also show if there are patterns or trends in participation. I then pair this inventory with a second evaluation instrument from Beyond the Bake Sale (Henderson, Mapp, Johnson & Davies, 2007). This instrument uses five domains (building relationships, linking to learning, addressing differences, supporting advocacy, and sharing power) to help educators identify which of four versions of family-school partnerships best describes their school (partnership, open-door, come-if-we-call, or fortress). To help them to see patterns, I ask students to identify which version of partnerships their schools represent for each domain and place a sticky note in the appropriate location (see Figure 1). While most people would say they have a partnership school, especially at the elementary level, many individuals are surprised with the results of this survey. There are areas suggested, such as including parents in curricular decisions, many of my students have not ever considered.

Between these two instruments, my students begin to get a clearer, and more accurate, picture of their schools’ strengths and needs with regard to parent and community partnerships. They are then asked to develop a family and community partnership grounded in the data they have collected from these two sources. I encourage them to think about how they can move their school to a higher version within one domain of the Beyond the Bake Sale rubric while also using some of the descriptors from the Epstein inventory to help frame goals and action steps. The projects that have emerged from this project have been organic, deeply-embedded in individual school needs, centered on literacy, and overall impactful. One resulting project was discussed in this blog by Hannah Kottraba in June when she wrote about her family heritage project. Other examples have included virtual science activities where parents and students engage in disciplinary literacy to solve scientific problems; pre-k students engaging in pen pal writing and subsequently building a garden with members of an assisted care facility (see Figure 2); online interactive math resources (focused on literacy needed for word problems); workshops that coach family members how to support reading with all ages of students; family culture exhibits; writers’ gallery celebrations; and international student shadowing days where high school students serve as hosts for international graduate students learning about America’s education system. Many of these projects addressed family and community populations who are often underrepresented in schools, and several have become multi-year or ongoing events.

It is important to remember that such projects are many times singletons, snapshots that occur once as a result of a course; the impetus being the need to complete a class assignment. I am not so naïve as to think these class assignments have suddenly made every school my students teach at a Partnership School. What is important is the paradigm shift that occurs as teachers undergo this process. They begin to seek out ways to better meet the criteria established by these two inventories; they become more attuned to cultural differences that may be acting as a barrier to some families and making them feel unwelcome with the school space; and they become more appreciative of the funds of knowledge parents and family members bring with them.

About the Author

Dr. Jennifer D. Morrison is an instructor at the University of South Carolina. Her experiences include being a middle and high school English teacher, gifted education resource teacher, and instructional coach. She earned her Ph.D. at the University of Nevada, Reno, in Language, Literacy, and Culture. She is a National Board Certified Teacher (AYA/ELA), an alumnus of the Teaching Shakespeare Institute at the Folger Theater in Washington, D.C., and has won multiple awards for teaching and writing including NCTE’s Paul and Kate Farmer English Journal Award and AERA’s Dissertation Award in Research on Teacher Induction. Currently, her research focuses on adolescent, digital, multimodal, and disciplinary literacies as well as narrative and qualitative methodologies.