This post is written by Linda Cato. You can find out more about Linda at the bottom of this post.

The classroom is charged with an energy of quiet focus: ten students patiently mixing rainbows of watercolor on paint trays and carefully painting in rows of squares on pieces of large, gridded paper. The students work around one large “studio table” created by pushing together several desks, which allows for ease as they assist and encourage each other through what was initially seen as a painstaking task, but is now met with curiosity and reflection.

“I never knew I could mix so many colors with just three! And I never knew that I could see my feelings!” says one student.

“To be honest, I thought I was gonna hate this, but I feel so calm right now,” says another.

Visual arts pedagogy holds the inherent potential to foster literacy across disciplines, while also nurturing key critical literacies such as hope. Art making (and all creative work) is, in its greatest sense, an act of hope, a powerful pathway by which we bring forward what lies beyond words, engage in bold envisioning, and exercise the right to dream. Educator and scholar Jeff Duncan-Andrade defines critical hope as the ability to assess one’s environment through a lens of equity and justice while also envisioning the possibility of a better future (Dugan, 2017; Duncan- Andrade, 2009 as cited in Bishundat, Philip, and Gore, 2018). Following my curiosity regarding the classroom as an incubator of personal and community well-being, creativity, and literacy, I have been striving to design projects which nurture both critical literacy and critical hope, with a nod to SEL and visual art standards. My goal is to walk a path of discovery alongside my students, whereby we build the capacity and language to craft essential and provoking questions and invite expansive answers through our creative journeying, while laying the foundations for personal and collective transformation and growth.

The unit, based on watercolor technique and color theory, set us on a path of self-reflection and connection. Introduced towards the end of the term, it bridges what we have seen and heard from the artists explored in this course (Kusama, Wiley, Butler, Glinsky, Gee’s Bend Quilters, among others), linking their experiences to the students themselves, with a focus on the storytelling power of color. Color, along with other forms of creative expression, is a powerful tool that can be used to express personal narrative, work with challenging emotions, and foster positive states of mind. (The Foundation for Art and Healing, 2022).

We began by looking at and responding to art that emphasizes the color red. Students offered insights as to what the red felt like to them, and what stories the red was telling in each painting. For some students, red felt like agitation or anger, for others, celebration and love. From their discussions, it was clear that they understood the personal nature of color as well as its potential to evoke emotion.

After our initial discussion, I passed out large sheets of watercolor paper and asked each student to create a grid on the paper, using rulers and pencils. I then began a demonstration of how color families can be mixed from three root primary colors – red, yellow, and blue – modeling the creation of a watercolor rainbow of colors of varying brightness, intensity, and opacity. I used the demonstration as a think-aloud, reflecting out loud as I worked, using vocabulary specific to the visual arts discipline and this lesson (“I see that mixing complementary colors has a specific effect on the value of color”) and taking time to pause and look at my work in order to offer reflective questions,”I wonder how the story of this orange will change if I add two drops of green?” and “Ohhhh that looks a little more like a shadow color, gives me a low-energy feel”…. I also note that “As I fill in this grid with all these colors, I am reminded of how many emotions arise throughout my day, one after the other….. “, connecting the activity to wider learning and laying important groundwork for the individual reflections and class discussions to come.

After completing about a quarter of my grid, I invited students into the process, continuing to work alongside them for several minutes. Pausing my work, I circulated around the room, engaging students in reflection and inviting questions. Once students had filled in the grids, we paused for a mindful reflection on the process and on the myriad of colors that covered the table. Referring to the Feeling Wheel (Wilcox, 1982) they named their colors with the corresponding feeling, writing the emotion on each square. We closed the session with students sharing their completed grids along with insights into their experiences and learning, acknowledging not only how different the grids are from each other, but also how beautiful and satisfying it is to see them all together.

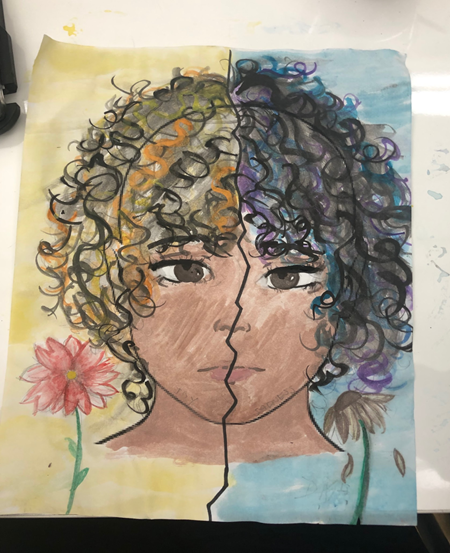

The next step in our exploration was to create a self-portrait using the color mixing techniques. We began with a group share, with students identifying and sharing the dominant moods they have experienced over the past week. Most students reported feeling tired, sad, bored, and stressed. I invited the students to consider how we might use color to connect to states of joy, peace, calm, and ease while demonstrating some techniques they might use to sketch out the silhouette of a head and neck, which I then divided in half by drawing a line down the middle of the face from top to bottom. Once all students had completed their drawings, we referred back to the Feelings Wheel. I invited the students to choose one emotion they had felt in the past days, and then identify a contrasting emotion and to write them on their drawings, on either side of the face. Next, students were guided to mix two different palettes, each representing one of the emotions they chose to express. Using their mixed colors, they painted in the portrait, one half at a time.

As the class worked with care and focus, I circulated around the room, responding to questions and comments. When all the portraits were finished, we shared the art and some words about the overall experience. Some expressed surprise at how their mood lifted as they worked on this project, and overall the class agreed that they experienced feelings of hope after representing themselves in colors connected with positive emotions. The group share was definitely a moment of connection for the entire group: we had touched a moment of collective critical hope. Through the shared creative experience and dialogue, students understood multiple perspectives while still connecting to self.

Given the concerning statistics regarding adolescent mental health, it is imperative that we are supporting our students in their awareness and understanding of their emotions, helping them develop the skills and tools they can use throughout their lives. In this particular instance, creative work is the vehicle of exploration. Creative expression supports the development of emotional literacy by inviting curiosity and reflection. Emotional literacy is directly tied to critical literacy in that it empowers individuals to deepen their own self-awareness while equipping them with tools of self-advocacy. Critical literacy in turn lays the foundation for critical hope as students find courage to envision, engage in new ways of experiencing, and exercise their self-efficacy.

References

Bishundat, D., Phillip, D. V., & Gore, W. (2018). Cultivating critical hope: The too often forgotten dimension of critical leadership development. New directions for student leadership, 2018(159), 91-102.

The Foundation for Art and Healing, artandhealing.org 2022

Willcox, G. (1982). The Feeling Wheel: A Tool for Expanding Awareness of Emotions and Increasing Spontaneity and Intimacy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12(4), 274-276.

This post is written by Linda Cato. You can follow Linda on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/lindacatoarts/.

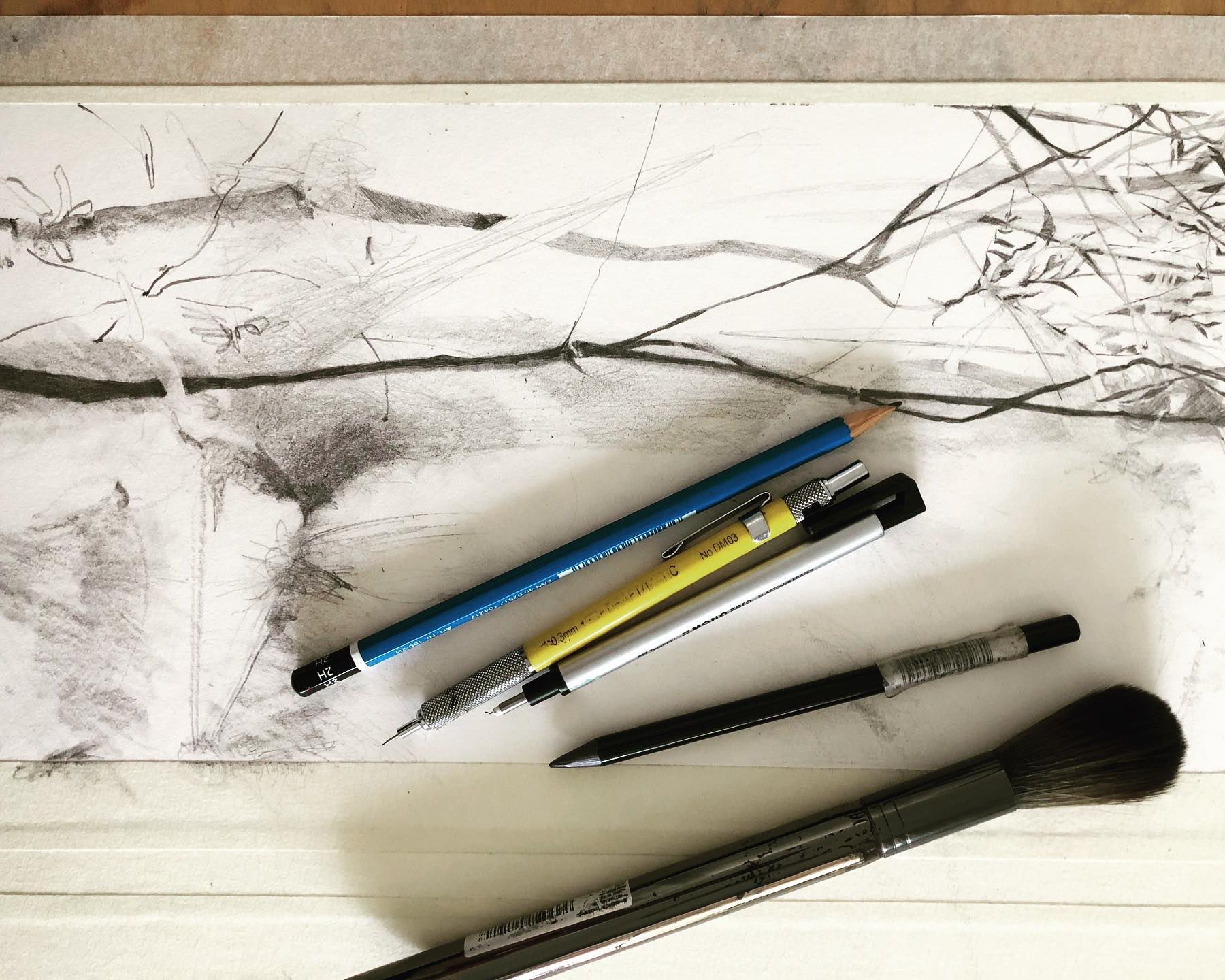

Linda currently serves as a high school visual arts instructor with the Chapel Hill-Carrboro School District, after relocating to NC from the desert Southwest. Following a strong interest in schools as spaces of wellness and healing, Linda recently completed certification in Social Emotional Arts through the UCLArts and Healing program. Linda’s wish for all students who pass through the classroom is that they touch joy and possibility, and experience the power of inquiry and bold imagining. Linda is also also a mixed-media visual artist with an active studio practice. The created art is grounded in observation and experimentation, and considers the interconnectedness of human experience, spirit, and the natural world.