By: Kim Ferrari, South Carolina High School English Teacher

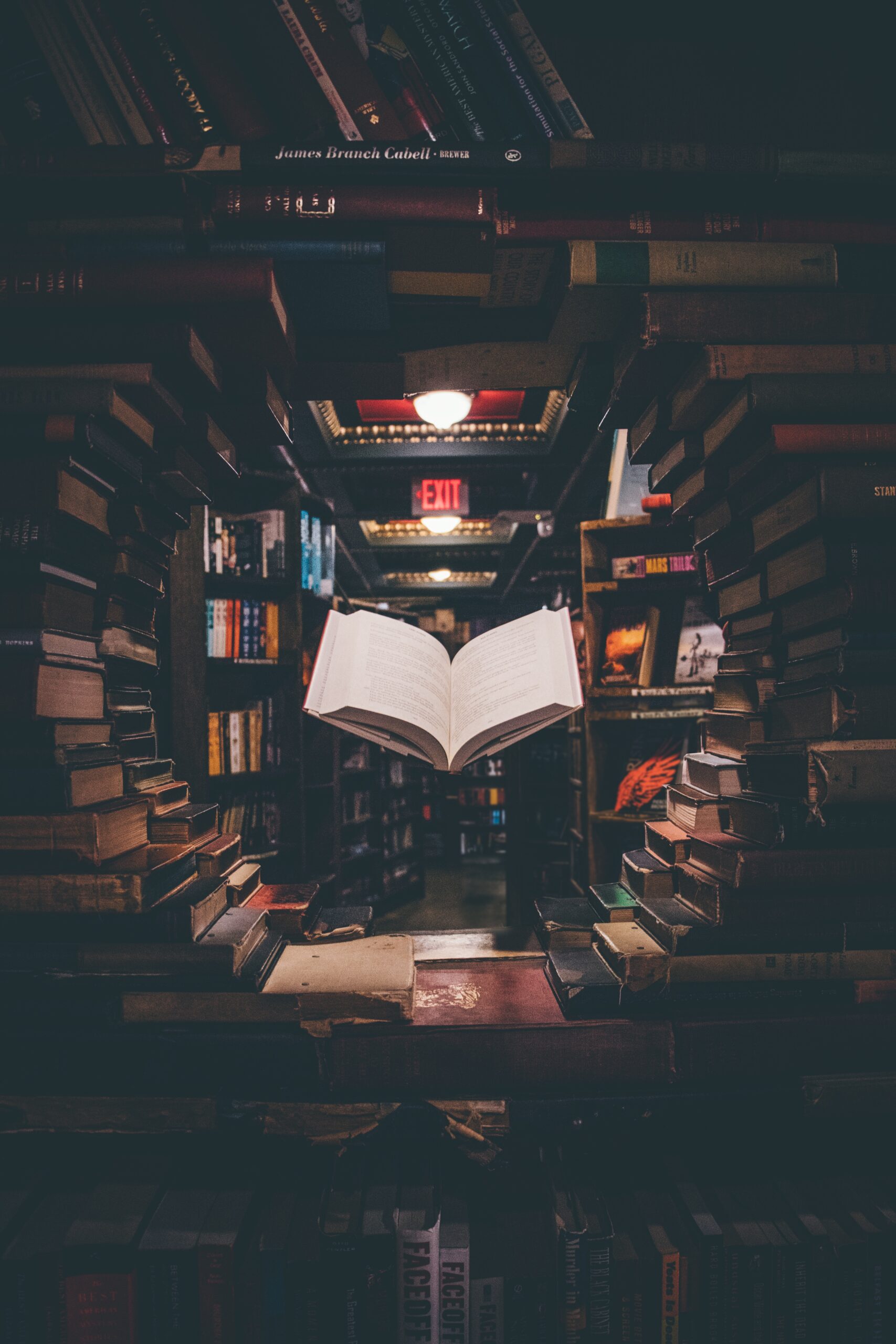

“I hate reading.”

“I don’t read.”

“Books are boring.”

“I’d rather watch the movie.”

These are all statements that I have heard from my high school students throughout my time as an English teacher. At first, I would get disappointed when I heard a statement like that from one of my students, but now I smile and nod at them when they say that because I know that by the end of their semester with me, they won’t have such strong feelings against reading.

What once felt like pulling teeth now feels more like cheering. What is the secret to getting students to not hate reading and maybe actually even fall in love with it? Well, it’s not so much a secret and more just a matter of taking the time to help students find the right book for them. For some students this is done in a matter of minutes, while other students might take a little longer.

Host a Book Tasting

One of my favorite ways of helping students find books that interest them is by holding a book tasting (also known as a book pass or book speed dating). Early in the semester, I work with my media specialist to pull a wide variety of mostly YA novels in different genres: action/adventure, romance, realistic fiction, sci-fi/fantasy, dystopian, historical fiction, graphic novels/comics, sports, and mystery/thriller. We sort the books onto different tables by genre and students rotate through the stations. At each station, students choose one book to sample for 3 minutes, and they are instructed to read the front and back covers, the inside cover, and begin the first chapter. After the 3 minutes has ended, students decide whether the book is a yes, a no, or a maybe, and record it on their graphic organizer. They then rotate to the next table with the next genre and the process repeats.

After students have rotated through all the genres, I pull aside anyone who still needs help finding a book and work with them to look for options that might interest them. Before we leave the media center, students check out one book, though I always have several students asking if they can check out more than one. Depending on how long your class periods are and how many students you have in each class, you can modify how this is set up, but I have found that exposing students to different genres helps them to realize that just because they don’t like a specific type of book doesn’t mean that they don’t like all books.

The Importance of Modeling

Modeling reading for students is important, so while they are reading, I spend the first few rounds circulating the room and “tasting” books. After a few rounds though, I start to look for students who have yet to find a “yes” book and use what I already know about them and what they have rated the books they have already previewed to help me suggest titles at their next station.

Prioritizing Reading

Once students all have books to read, we begin every class with independent reading. The first few days are usually a bit of a struggle as students learn the procedures and expectations for this part of class, but after a week or so, independent reading becomes a regular part of our daily schedule and students know what is expected of them. Our daily schedule is built around independent reading to ensure that no matter what, we have time to read. While students are reading, I walk around the room reading my book. This allows me to model independent reading for them because they can see all the different books I read and it allows me to quietly redirect students who may be off-task or distracted. Modeling reading for students helps to encourage them to read and motivates them to continue reading. Because I am reading when my students are reading, I am able to read a lot of books every year, which helps me recommend titles that I think students will enjoy based on their interests. Independent reading is a skill that needs to be developed over time, so we begin with reading for 7 or 8 minutes and build up to around 15 minutes as students’ stamina increases. The more students are engaged in their books, the longer they will read for, which is another reason helping students find books that interest them is so important. If I notice a student appears to be disengaged with their book, I keep an eye on them and if a day or two later, they’re still not engaged, I have a conversation with them and recommend a different book.

Making independent reading a priority in my classroom has led to increased reading stamina, higher engagement with books, and significantly fewer groans when I announce it’s time to read. At the end of each semester, I ask students to reflect on their experience and every year, there are positive comments that remind me why I put so much effort into helping students find the right books and making independent reading such a focus. Students share that this is the first time in years that they’ve finished an entire book, that they found themselves looking forward to independent reading each day, that they didn’t know reading could be fun, and that our independent reading time gave them a chance to relax. Some students even come back after they leave my class asking for book recommendations or if they can borrow one of my books, so I get to continue to foster their love for reading. When students come back to me years after graduating high school and tell me about the books they’ve read lately, I know I have done my job of creating lifelong readers, which to me is the ultimate goal.

About the Author

Kim Ferrari is an English Teacher at Manning High School in Manning, SC. She received her Bachelor of Science in Secondary English Education from the University of Maine at Farmington and is working on her Master’s in Literacy from Clemson University.