By: Dr. Todd Lilly, University of South Carolina

(For what it’s worth, this blog is peppered with a few hyperlinks to entertain the reader and to illustrate New Literacy Studies… for what it’s worth. Enjoy!)

Here’s a scene you might recognize: Everyone is concerned about the mental health of the young prince. The father of his fiancé finds him alone in a room in the castle, absorbed in a book. “What do you read, my lord?” The prince stops reading, flips through his book as if to try to find an answer to this most-important question. Then, as if making an astonishing discovery, he answers: “Words. Words. Words!”

I know what you’re thinking: “I’m not an English teacher! What’s this got to do with me?” Well… In the context of New Literacy Studies…Plenty. For what it’s worth, there was certainly a whole lot more in the prince’s book than words, and that should interest all of us.

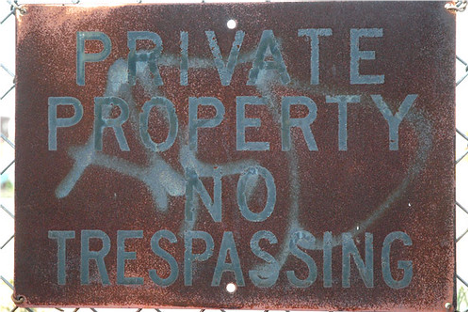

Our house backs up to a popular public recreation area, so our Home Owners’ Association (HOA) posted signs: “Private Property/ No Trespassing!”

Many third graders would have no trouble sounding out the words:

“Pr…Pr… Pr as in Pretzel”

“Tr…Tr…Tr… as in Truck”

Hmmmm… I have no idea why the ‘ATE’ in “ PRIVATE” shouldn’t be pronounced like “8” or why the ‘ei’ in “eight” should. What exactly is a ‘ə’ anyway? “I’m not a reading teacher!” Anyway, that’s the gist of old literacy studies.

So, maybe we secondary teachers don’t actually know all that much about Old Literacy Studies, but still, we get the idea: If kids know enough rules to sound out words, they can read just about anything we give them, whether it’s a social studies text book or Hamlet. It’s an autonomous design: Learn to decode and you have power. It’s that simple.

Well… actually, no, it’s not that simple. And neither are the literacy events and practices we expect students to engage in when they enter our classrooms. That’s where New Literacy Studies gets interesting.

About 30 years ago, just about the same time as “You’ve got mail!” several out-of-the-box smart people from a few English-speaking countries got together and kicked around the idea that literacy was more than decoding, semiotics, and semantics. In the mid-1990s they saw how the rise in popularity of digital technology had the potential to radically change the way people produced and consumed all kinds of texts. They got so excited about this “New” idea that they made plans to meet in a small New England town, New London, New Hampshire, just to talk about it. And they did. They came to be known as “The New London Group.” What was their conclusion?

This might be a good time to get up, stretch, visit the bathroom and/or the refrigerator, maybe do a little yoga… Ok, here goes:

They decided that literacy is a social event embedded in a complex web of power-laden social and technological contexts that all revolve around texts and language. (Yes, English teachers; that’s what Pygmalion, written a century ago was all about… “Duh!”). Another way of looking at it is that literacy exists by means of some technology (a book, a sign, a billboard…) in a social space between a producer and a consumer. It involves ways of speaking, thinking, acting, and believing, which would mean that one’s identity and membership in social groups can and does affect meaning. This mutation from literacy as merely decoding to literacy as a social practice was coined “the social turn.”

So there. Move over Gutenberg!

That’s pretty much what they could agree upon. I can imagine the discussion got a bit contentious when they started thinking about the definition of “text.” Is an embroidery of birds on a pillowcase a text? Seriously, that’s an important question in the context of multiliteracies, but we’ll save that for another blog.

For now, let’s consider the “No Trespassing” sign above as a text. It’s not a Falkner novel or a Shakespeare play, “but ’tis enough, ’twill serve.”

Someone created the sign, someone nailed it to a tree, and there are indeed people who have come along and read it. The sign successfully transfers an idea from the sign’s producer to the consumer: “Keep off OUR property!” The literacy event is accomplished. What more might these New Literacy folks say?

Well…plenty. They would point out that that the posting and reading of the sign was but an event, part of a larger practice that brought together myriad social and power connections. The sign was initially a reaction to a legal context. At our annual HOA meeting, our lawyer noted that if we hadn’t posted these signs, we would be liable for any damages incurred by anyone who stepped onto our property. (Don’t you just LOVE lawyers?)

There’s also, of course, a power dynamic. Who are these potential trespassers? We can only imagine them happening by and reading our message: We own something/ you don’t/ you can’t have it/ We deserve it/ You don’t. Nanananana… “The sign said you got to have a membership card to get inside…Ugh!”

I’m sure y’all noticed the graffiti on the sign, probably a tag, a unique form of literacy that a certain group of people (in this case, graffiti writers) use to identify their work: Loosely translated, it says: “Hey, I’m somebody too!” And am I wrong to deduce a bit of anger and animosity?

If literacy, then, is all about contexts and social memberships, who gets to decide meaning? ELA teachers have heard this refrain before; it’s not new.

Student: “Mr. Lilly, I think Robert Frost’s ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’ is about Santa Claus.”

I can’t remember my reply, but now in my current life, I call forth the literacy gurus:

Louise Rosenblatt would have said, “Ok, a reader has a right to make meaning out of otherwise meaningless symbols.”

E.D. Hirsch might exclain: “Hogwash! Go ask Frost!”

Michel Foucault would look up from his bath: “Go for it kid ‘cuz Robert Frost is dead!”

Here’s some song lyrics that were a bit more popular than Frost when I was a kid:

“Paranoia strikes deep. Into your life it will creep. It starts when you’re aways afraid. You step out of line, the man come and take you away.”

–Stephen Stills

In the words of the great Yogi Berra: “It’s like déjà vu all over again.” For you youngins (“Ok, Boomer…”), long before Post Malone, Lizzo, Chance, JayZ/ Beyoncé; long before Justin and Taylor, even before Back Street Boyz and still further back before AC/DC there was the Buffalo Springfield. Band member Stephen Stills, in 1967, during the tumultuous years of the Vietnam War and Civil Rights, immortalized these words in his “For What It’s Worth” which rocketed to #7 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Ok, what’s it about? Vietnam Protests? The Generation Gap? Was it a precursor to NWA? “Words, words, words.”

Nope, it was about an event in which riot police confronted a large gathering of young people who came together to protest a curfew in Hollywood, California. But to hundreds of thousands, it represented a division in America, an anti-establishment movement that exists to this day. If you don’t recognize the lyrics, I’ll bet if you click on the above link, you’ll recognize the tune. And if so, is the tune an integral part of the text? (If you actually click on that link, you’ve officially become involved in New Literacy Studies!)

Ok, that’s cool, but here’s the kicker: What happens to a text when it becomes older than the generation for which it was written? In the 1990s, about the same time the New London Group met in New Hampshire, the Buffalo Springfield band members (minus Neil Young, of course) all in middle-age, allowed their song to be used in a Miller Beer commercial. What?! An anthem of protest converted into an anthem of capitalism?! “Something’s happenin’ here. What it is ain’t exactly clear…”

Well, actually, it is quite clear. The baton had been passed to a new generation. The context, the setting, the medium, the identities and power dynamics of the producers and consumers had changed from social injustice to quaffing a cold one. If you think about it, it’s much like what kids experience when they march from math to social studies to ELA and to lunch, all in the course of a typical morning. Everything changes. Students might read the same word in each class’ lesson, (“plot,” for example), but it will have a totally different meaning as the bell rings and students march from one class to another. The fact that they can pull this off day after day demonstrates remarkable sophistication. No science teacher is going to accept a lab report written as a rhetorical composition. As soon as students cross the threshold into the science room, they abandon the aesthetics of poetry that defined the day’s ELA class and magically conform to the inductive reasoning espoused by Francis Bacon, whoever he was.

Alex Watson, CC.org

Nothing is benign; a literacy event is always at the intersection of competing contexts (identities, histories, cultures, purposes, technologies) that can wax and wane over time. While in the course of a single day, we demand students think like a historian, think like an artist, think like an author, think like a scientist, think like a mathematician, think like a musician; all of which require a different literacy practice.

This past March, those kids were sequestered to rooms in their home “castles” somewhere in the village or in places even Verizon won’t go. And at the flip of a switch we were found alone at our laptop at our kitchen table desperately trying to replicate the old literacy practices of a face-to-face classroom and project it onto the new, unseen, unfamiliar contexts of the students’ existence. We tapped out words that were meant to convey the same curriculum and the same standards, but we all sensed the inevitable: “Something’s happening here/ What it is ain’t exactly clear.” More than a few of us have been confronted students’ equivalent of “No Trespassing/ Keep Out;” maybe not in so many words,

This could be a very long, very hot summer!

“What a field-day for the heat. A thousand people in the street. Singing songs and carrying signs. Mostly say, “Hooray for our sign!’…You step out of line, the man come and take you away. It’s time we stop, children, what’s that sound? Everybody look what’s going down…”

For what it’s worth, this New Literacy Studies stuff never gets old.

“It’s only words and words are all I have to take your heart away” –Shakespeare (Just kidding; it was the Bee Gees, and if that makes a difference to you, welcome to New Literacy Studies!)

About the Author

Todd Lilly has been a teacher for over 40 years, the majority of which was invested in middle and high school ELA and theater classes in and around Rochester, NY. Over the past 10 years he has served on undergraduate and graduate faculties in Wisconsin and currently at the University of South Carolina. He earned his Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include out-of-school literacy practices and the stories of marginalized, disenfranchised students. He is married to Dr. Catherine Compton-Lilly who holds the John C. Hungerpiller chair in the College of Education, University of South Carolina