This post is written by Brooke Hardin. Read more about Brooke at the bottom of this post.

Let’s Get Personal

I am a white female who began school in the mid-eighties and entered a mostly white, suburban, blue ribbon-winning elementary school at the precocious age of five and a half. To my knowledge, no one had conversations with me about any differences in my family, and I had no reason to think there were. That is until I entered kindergarten and was met with weekly stories in books and readers where the families portrayed were white (or peach colored as the illustrations showed) and comprised of a mother, father, son, daughter, dog, cat, and possibly a goldfish. No big deal, right? The problem was that by this time, my father had not lived with me since I was two years old, and I had both a mother and a stepmother, both of whom I adored. Let’s not forget, I did not have a dog, cat, or goldfish; in fact, I had had two hamsters, both of which escaped their caged confinement, chewed holes in our carpet, and somehow disappeared. My family dynamic – made up of my mother and me in our townhome, my father, stepmother, half-brother and half-sister in another home that I visited every other weekend, and two stepbrothers that lived out of town – was not found within the pages of the books read to me by my teachers or those that were available for me to read as I moved through the elementary years. In fact, it was not until much later that I saw someone “like me,” the youngest child in a blended family, in a book.

While my story is innocent enough and did not impact my love of reading or success with it, it could have, and it is reflective of what so many students face today in their own classrooms. Their stories, culture, historical backgrounds, family dynamics, and more are absent from the texts in the libraries of classrooms where they spend hours learning each day. Moreover, educational policies limit what is possible for teachers to include in classroom libraries and how they can teach certain topics. At the same time, authors are publishing texts that portray a vast array of stories, online resources covering multiple viewpoints are abundant, and students have access to more information than ever before, given their proclivity for digital engagement. How does a teacher provide a wide-ranging classroom library while following a state or district’s policies on instructional materials and literature? While this is a real challenge, teachers might consider some seminal theoretical and research-based ideas that support the need for diverse classroom libraries.

Why Do Classroom Libraries Matter?

In the last several years, the hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks has gained momentum and attention. Books and teaching have the capacity to change lives. Still, to do so, teachers must have the professional freedom to reflect regularly on the literature landscape shaping their classrooms. They must consider the narratives found in their classroom libraries:

- How does the library shape students’ collective memories of their own + ‘others’ histories?

- Whose voices seem valued + whose are not?

- Whose stories are absent or silenced?

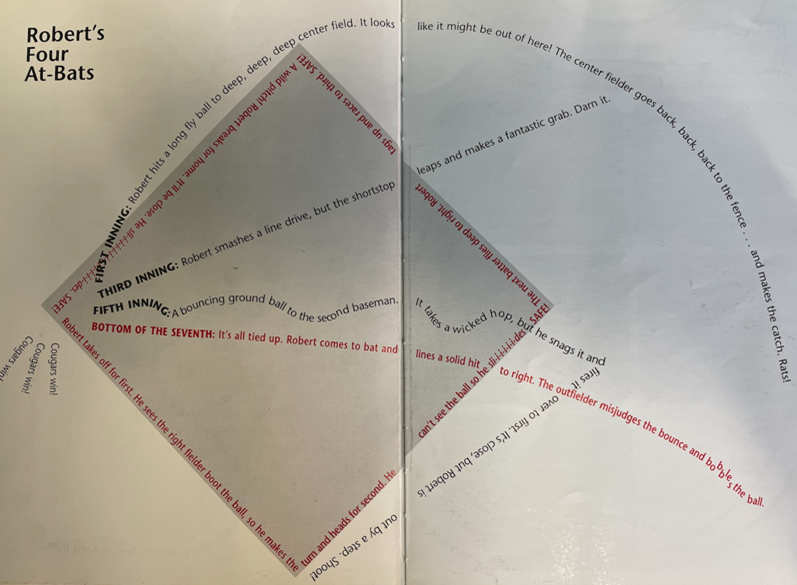

Theories like Rudine Sims Bishop’s (1990) idea that texts can act as “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors” and Rosenblatt’s (1978) transactional reader-response theory show educators how the use of diverse texts has the power to increase content learning and empathic responses. However, both theories center the reader in the text. Another way to think of literature is to center the reader along a continuum with any text; it either reflects a lived experience or presents the opportunity to show a new or different experience. This then presents an opportunity to learn, think critically, and gain understanding.

Let’s take the following example of a teacher using adolescent historical fiction literature to provide instruction about the American frontier and pioneer life in the early 19th century. A teacher might reach for a classic like the Little House series published by Laura Ingalls Wilder in 1971. While entertaining to some, the series contains racism and portrays an incomplete story of what life was like on the prairie. A more comprehensive unit of study might include Louise Erdrich’s (1999) The Birchbark House, which reverses the narrative of 19th Century Native Americans and shows the life of an Ojibwa family in 1847. Additionally, a teacher might include the book Prairie Lotus, written by Linda Sue Park in 2022, which features the story of Hanna, a half-Asian girl who wants to go to the one-room school, make a friend, and help in her father’s dress-goods shop. Additionally, teachers would include images, diverse primary source documents that impacted people’s lives, informational pieces, and more. In this way, we do not abandon all classic literature but expand the approach to literature selection (Zapata et al., 2018). This example shows how teachers might think about building their instructional classroom library; that is, the library from which they pull resources for teaching skills and content.

Teachers must also be intentional about the literature students have access to in the greater classroom library, the bookshelf, or the space in the room, where students can personally select texts to read during independent reading time or at their leisure. As shown in research regarding school-aged pupils, there is a direct correlation between reading skill growth and sustained time spent reading (Allington, 2014; Locher & Pfost, 2020). Thus, the classroom library needs to contain literature that appeals to students’ interests, represents a variety of lived experiences, and connects to contemporary issues. Given this, it is likely that the exact controversial topics (i.e., race, sexuality, culture, history, etc.) keeping space in policy headlines will be present in some of the classroom library literature. So, how does a teacher advocate for these materials to remain?

Policy’s Effect and Advocacy Moving Forward

Recent proposed legislation in headlines and bills aims to limit or ban literature that is based on what is deemed as controversial topics, including American history, family, race, and more. However, banning literature and these topics is detrimental to the engagement, critical thinking, and overall learning possible in today’s classrooms. Certain bills go so far as to be explicit about how teachers can and cannot teach certain topics, prohibiting some ideas and prescribing the verbiage for others. For example, teachers in some districts have been told they cannot use literature that talks about race or could be deemed Anti-American. In this way, teachers are being told to teach prescribed content that is likely not wholly accurate and more importantly, is not culturally inclusive of all students.

More than ever, teachers must be wise about advocating for their students’ learning and “following the rules” while also providing thorough instruction and helping students become thoughtful global citizens. When teachers are selecting classroom library literature and instructional materials, they must be critical consumers themselves. Look at your class roster; whose culture is present in the materials? Whose is missing? Does every student have ample opportunities to find a book that represents them in the classroom library? Using interest inventories (Williams, 2022) at the beginning of the school year and using the information gathered to add new texts to instructional libraries and the larger classroom library is another option. Viewing instruction and the selection of materials through the argument presented here might provide teachers a way to build inclusive units of study that task students with critical considerations and keep teachers out of local headlines.

Additionally, consider speaking before policymakers; educators can use the theories calling for diverse books and relevant, multi-sided texts to sustain their pleas for professional freedom and all-encompassing classroom libraries. Finally, teachers facing book challenges or desiring more support for instructional freedom might consult some of the available resources such as the National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE)’s Intellectual Freedom Center (https://ncte.org/resources/ncte-intellectual-freedom-center/) and the We Need Diverse Books website (https://diversebooks.org/resources/addressing-book-challenges/), which is full of resources for teachers, parents, and librarians.

References

Allington, R. L. (2014). How Reading Volume Affects Both Reading Fluency and Reading Achievement. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 7(1), 13-26.

Bishop, R. S. (1990, March). Windows and mirrors: Children’s books and parallel cultures. In California State University reading conference: 14th annual conference proceedings (pp. 3-12).

Erdrich, L., & Littrell, N. (1999). The birchbark house. New York: Hyperion Books for children.

Locher, F., & Pfost, M. (2020). The relation between time spent reading and reading comprehension throughout the life course. Journal of Research in Reading, 43(1), 57-77.

Park, L. S. (2020). Prairie lotus. Clarion Books.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1988). Writing and reading: The transactional theory (No. 416). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Wilder, L. I., & Williams, g. (1971). Little house on the prairie. 1st Harper Trophy ed. New York, N.Y., HarperTrophy.

Williams, K. (2022, October 31). 12 reading interest survey questions to ask students and sample questionnaire. Survey Sparrow. https://surveysparrow.com/blog/reader-interest-survey-questions/

Zapata, A., Kleekamp, M., & King, C. (2018). Expanding the Canon: How Diverse Literature Can Transform Literacy Learning. Literacy Leadership Brief. International Literacy Association.

Brooke Hardin is an Assistant Professor of Elementary Education at the University of South Carolina Upstate. Her research interests include writing development and instruction for intermediate and middle grades students, teaching and learning through technology and new literacies, literacy professional development and teacher education, and interdisciplinary approaches to reading, writing, and the utilization of Children’s Literature. Her years of experience as an elementary and middle grades classroom teacher and curriculum literacy specialist frame her research interests and commitment to teacher education.

Photo by Darren Richardson on Unsplash