This post is written by Charlene Aldrich. You can learn more about Charlene at the bottom of this post.

I’ve always been a strong believer in the power of reading to identify important information and to grow decision-making processes. My mantra is, “Never tell someone what they need to know when they can find out for themselves by reading.” So, when I saw the book Micro Mentor Texts by Penny Kittle come up in my Facebook feed, I was especially intrigued by the idea that students might not need to read ALL of Romeo and Juliet to become knowledgeable of Shakespeare, his cheeky quotes, and 16th-century literature.

I’m not trying to sell you on this book, instead, I AM trying to sell you on the idea that mentor texts don’t have to be complete works that students gloss over to “complete the assignment.” Can it be that teachers can provide specific sample excerpts to achieve their literacy goals?

Spelling and Vocabulary

Research has affirmed the idea that successful readers and writers tend to have prolific vocabularies 1.

Useable vocabularies grow through listening and reading, speaking and writing2. I continue to believe in the developmental nature of language to support literacy development as I watch my granddaughter on her preschool journey to beginning reading. Her speaking vocabulary includes words and phrases such as “cheeky little rascal,” “plaster,” and “go through” because of her fascination with the very British show featuring Peppa and George Pig! She may never read them in the same context, but the foundation has been laid for multi-meaning words if she sees these and similar words and phrases in reading selections.

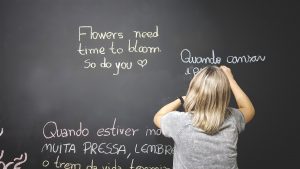

What does this say to educators and about mentor texts? Reading, writing, and oral language are tightly knit; introducing mentor texts as examples of effective writing “… promotes students to view, discuss, read, and create literature that affords opportunities for spelling and vocabulary development that are engaging, relevant and active”3.

Blog writers from ELA Matters share “3 Engaging Mentor Texts for Middle and High School”. One that supports vocabulary development is My Name by Sandra Cisneros. While the language is simple, Cisneros weaves it into rich literary devices such as imagery, simile, and metaphor. Students of all reading abilities see how to use their own vocabulary levels to develop descriptive works that require precise vocabulary.

Beyond spelling and vocabulary

In addition to growing spelling and vocabulary, mentor texts contribute to the development of other traits of effective writing: organization, conventions, sentence fluency, and voice. Mentor texts are examples for students to follow as they develop their own ideas through these traits4. They can be below grade level to make the traits obvious; they can be on or above grade level to meet the standards that require complex texts. They can include a wide range of styles – from classical literature to graphic novels. Teachers can use them to develop critical thinking and persuasive arguments. Students can read memoirs in preparation for personal narratives. The inclusion of authors and diverse topics can even mentor acceptance and open-mindedness. And never overlook the power and pleasure of picture books for growing storytelling.

Mentor texts are not restricted to the ELA curriculum. As state standards have shown through the inclusion of disciplinary literacy requirements, each discipline contains its own set of unique formats, craft, and technical language. Thus, each content area teacher has the opportunity to include quality mentor texts for students to emulate as they meet the reading and writing needs of each discipline. What do YOU enjoy reading in your discipline? How can students also find enjoyment in your choice of reading selections of your discipline?

My grandson introduced me to A Night Divided by Jennifer A. Nielsen. This book takes readers through life behind the Berlin Wall, beginning with the night it was built. Social Studies/History courses are meant to provide multiple perspectives to ensure accurate representation of diverse experiences. This historical fiction book opens with vivid language to introduce a school-age girl’s reaction to the lack of freedom that was imminent. “There was no warning the night the wall went up. I awoke to sirens screaming throughout my city of East Berlin. Instantly, I flew from my bed. Something must be terribly wrong. Why were there so many?” Individual excerpts from the book can be extracted as a mentor text for writing essays that focus on the value of freedom. Using this text as a mentor, along with showcasing other fictional or nonfiction realities of this time period, can support students’ ability to also write about their own experiences with freedom or war.

Using Model Texts

Students NEED high-quality reading selections that challenge them to grow in their personal literacy skills; after all, literacy is power. In addition to meaning-making, model texts provide examples of effective composition techniques5. Using them effectively becomes the goal. Robyn English (2021) offers this advice6:

- Be familiar with the reading selection and what you want it to demonstrate

- Be purposeful in your use; plan for single successes, not multiple attempts

- Be knowledgeable of the strategy or characteristic being taught

- Be flexible, returning to a single text for other purposes

- Be generous, sharing them as you would any book in your classroom library

In Short

Students need positive role models for growing into responsible adults. Likewise, they need effective models of texts for growing their literacy strength. As English notes in her text listed above, “Mentor texts support a teacher in modeled reading or writing.”

Charlene Aldrich is an instructor in the Office of Professional Development at the College of Charleston. While content-area literacy is her specialty, she also teaches Assessments in Reading, Foundations in Reading, and Instructional Practices as required by South Carolina for recertification. She serves as the Treasurer of LiD 6-12.