Kristie Camp continues to answer this question as she expands on the benefits of outdoor learning an environmental literacy. Read more about Kristie at the end of her blog.

Amanda (names changed) was not happy that we had brought the turtle back into our classroom, despite most of the class being excited about the prospect of having a class pet. She wrote in her journal that day, “I felt that we should have put him back, because didn’t we talk about how humans are messing up the environment this week while reading the whale shark chapter in World of Wonders? I really do hope we don’t mess this turtle caring business up.” Our weekly walks in the woods and the book we were reading together must have made a lasting impact on how Amanda viewed her role as an environmental steward. The rest of the class conceded she was right, and within a few days, we all participated in a rehoming ceremony for our turtle.

Studies have shown that positive experiences in nature develop long-lasting affective associations with the natural world, which often times translate into activism and advocacy for environmental causes (Křepelková, et al., 2020; Soga & Gaston, 2024). As a veteran teacher of 26 years in high school English language arts (ELA), I have found that outdoor learning not only serves as a powerful conduit to creative thinking and cooperative action, but it also lays a solid foundation for environmental literacy, as Amanda and her classmates demonstrated with returning the turtle to his home.

When I use the term environmental literacy, I refer to an individual’s ability and willingness to make ethical and research-based decisions about their environmental choices, as well as their desire to conserve natural resources (California, 2015; MAEOE, 2024; NAAEE, 2024). Environmental literacy does not manifest itself only at the individual level; it is also a cooperative and collective move toward learning how to participate in civic life for the good of all living creatures (California, 2015; MAEOE, 2024; NAAEE, 2024). Teachers who provide opportunities for cooperative learning outdoors foster those affective connections that just might grow into cooperative action toward sustainability that benefits us all.

As children grow older, their time outside seems to diminish. Students today have spent less time playing outside than previous generations (Schilhab, et al., 2018; Selhub & Logan, 2012; Williams & Wainwright, 2016; Zeng, et al, 2021). The less time students spend outdoors corresponds with an increase of time spent behind screens (Barrette, 2022; Jackson, et al., 2020). The increased time behind screens instead of outside has implications for teens’ academic progress and their overall wellbeing (Hicks, et al., 2021; Kuo, et al., 2018). Increased screen time paired with fewer opportunities for spending time outside and with others has contributed to rising mental health challenges and physical ailments for teens (Abenes, 2022; Barrette, et al., 2022; Hedderson, 2023) as well as a reduced ability to concentrate and more difficulty communicating with peers socially (Abenes, 2022; Nadeem & Van Meter, 2023). In addition, digital immersion has often lured students into relying too heavily on artificial intelligence to the detriment of their own originality and creativity (Daniel, et al, 2023; Zhao & Watterson, 2021).

Engaging with the physical environment and interacting with nature through multiple senses offer ways to mitigate some of the detrimental effects of too much screen time, and outdoor learning can benefit teens’ health and academic progress. Outdoor spaces are conducive for sensory experiences and creative activities that incorporate artifacts within the setting (Asfeldt, et al., 2020; Beames, et al., 2012; Quay & Seaman, 0216; Selhub & Logan, 2012). Lessons that reconnect students with the physical world and its artifacts offer sensory experiences that employ both cognitive and kinesthetic processing, thereby providing a more memorable and meaningful learning experience. If the context of the classroom expands so that students interact in a tactile way with the physical world that surrounds them, then their attention turns outward, opening the way for creative and imaginative expression simply because they have new physical experiences from which to think and create (Beames et al., 2012; Carpenter & Harper, 2016; Quay & Seaman, 2016). It also opens the way for environmental stewardship as students first learn to love their local landscapes, and that love often spurs protection advocacy for broader ones.

During our outdoor adventures, Amanda reminded us that we needed to leave Gerald the turtle in his natural habitat, but Jake taught us about his early childhood in the Philippines and told us stories about how he and his cousins would put spiders on a stick to see if they would fight.

Several of us responded in disbelief: “You didn’t really pick up spiders and put them on a stick, did you?”.

“Yes, we did. Let me show you,” Jake replied.

Within a few minutes he had a spider on a stick and had us looking for a companion to place beside it. About three of us leaned in, not blinking, as Seth placed a smaller spider within inches of the larger one. We didn’t even have time to pull out our phones to start filming before the larger spider whipped out its web and wrapped the smaller one into its death blanket.

After our exhalations of astonishment and awe, we began to toss questions at Jake about his childhood. “We didn’t know you were born in the Philippines! When did you come to the US? Do you speak another language?” Jake kindly told us about his family in the Philippines and his move to the United States in elementary school. In his journal that day, he wrote about how that day’s experiences brought back memories he hadn’t realized he had forgotten. The rest of us walked away with a little more thorough understanding of each other. We were able to relate to the natural world in ways unique to our cultural experiences, which created a more democratic and cooperative learning environment for us all.

Before I share more examples from our outdoor classroom, I must acknowledge the privilege that I enjoy. Our school has numerous places for outdoor lessons — courtyards, access to the track and practice fields, and a wooded area across the street from the school where the cross-country team runs — and my current and previous principals have encouraged my use of our green spaces. I understand that not all teachers have access to safe outdoor spaces and supportive administration, but just about any outdoor space can be made into an engaging classroom, and I hope researching the benefits of green spaces in schools will fuel the movement to provide outdoor learning space for all students.

Here are some ways I have found to take class outside for numerous benefits, including participating in memorable content lessons, building classroom community, and cultivating environmental literacy. Of course, the examples come from an ELA class, but the process is easily adaptable to just about any discipline.

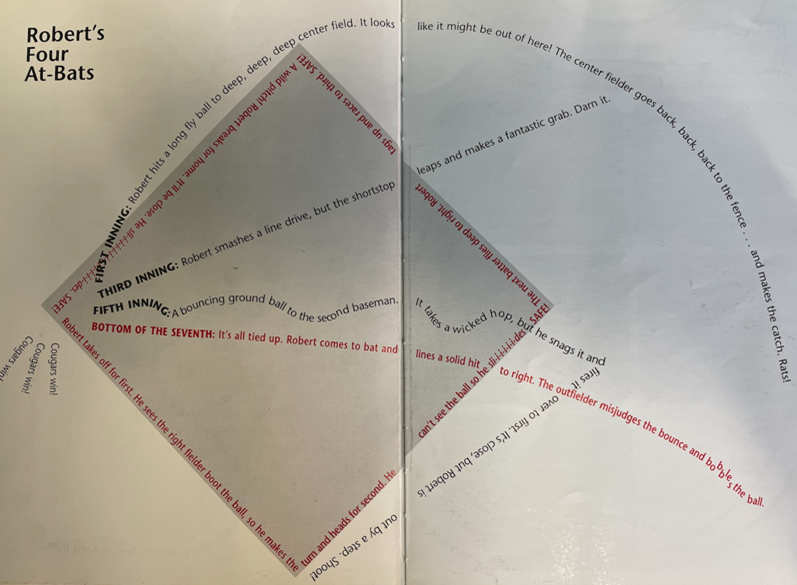

String Journals

I learned about string journals when I spent a week studying Thoreau at the Walden Woods Project in their summer program, Approaching Walden, in 2019. I took what I learned and adapted it for my class in the fall of 2020. I printed and laminated a name tag for each student and attached a waterproof twine.

Students found a place in the woods where they wanted to return throughout the semester, and they hung their tags there. Each time we went to the woods for an outdoor lesson, we began with a moment of observation and writing at our string journal spots. By the end of the semester, students had a time-lapsed set of descriptive writing that detailed changes in the spot from August to December. This lesson works for writing instruction as easily as it will for scientific notetaking or geological study. Students can practice sketching and documenting the environment as a professional naturalist, archeologist, or geographer might.

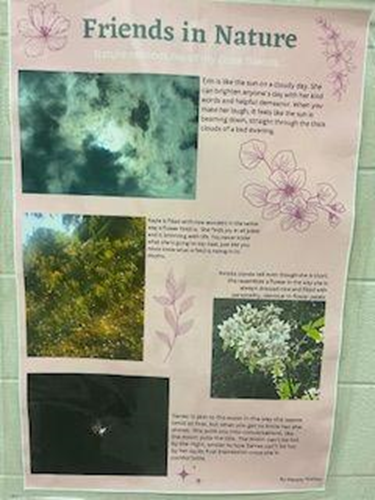

Photo Essays

Students can create a photo essay (such as in the model of Humans from New York, for example) from images taken while outside around campus. Students learn to select images carefully for symbolic purposes while making the most of limited written text space. The content of photo essays is dependent on the content being taught (for example, artistic expression or documentation of natural change over time) and therefore adaptable for any discipline. Social studies classes might focus on natural resources or local history, whereas world language classes might center vocabulary acquisition.

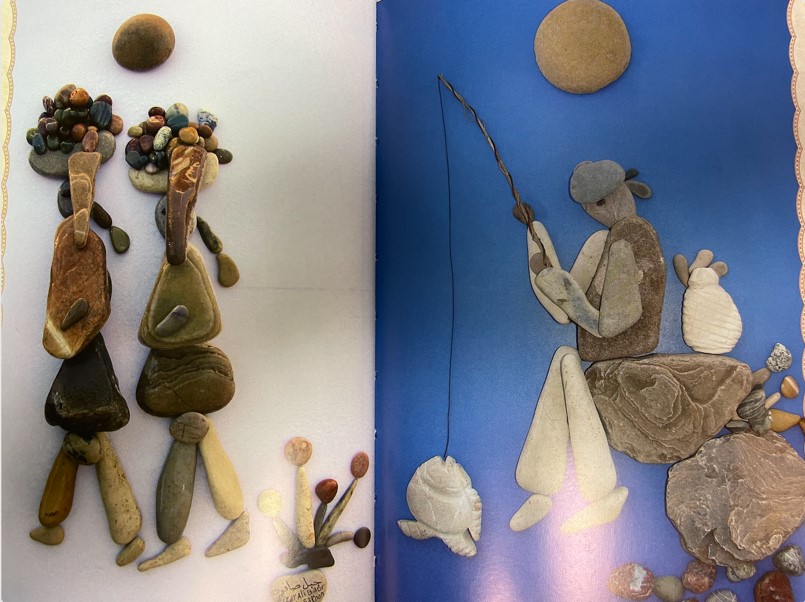

Art Collections, Collages, and Memory Jars

While outside, our class has collected interesting artifacts from the woods including a mysterious jawbone, persimmons, and unique leaves and wildflowers. Students have also brought back live creatures – caterpillars, unknown white creepers, and our pet turtle – even though we cannot keep those as part of a collection. The collections represent students’ adventures outdoors, and a story almost always accompanies the item selected, which forms the basis for original writing, full of sensory imagery and emotive language that I don’t often see in their traditional classroom assignments. We have also made art collages from artifacts gathered outside and students articulated reasons for the items they chose to include, again extending their understanding of symbolism and metaphor.

Yet, a biology class might create a leaf collection to be labeled and categorized. A geology class might collect rocks and minerals for a similar display. A math class might collect examples of different shapes or different representations of the same angle or slope.

Using Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s (2020) example in her chapter, “Firefly Photinus Pyralis” in her nature memoir World of Wonders, In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments, we collected items from the woods to store in memory jars for our class as a way to commemorate our outdoor adventures together. What physical representations do we want to keep as memories of our shared experiences outside? These collections can also provide materials for a multimodal art display in an art class or indicators of geographical descriptors for one’s local environment (for example, what do we find in the woods that demonstrate we live in a foothills region?) in geography class.

Blood Pressure Checks

After reading an article about forest bathing and how spending time outside reduces people’s blood pressure, we decided to put the article to the test. Our school nurse graciously helped us by taking each student’s blood pressure before we went outside and again when we came in after our walk outside. We recorded the data anonymously and analyzed it; while our findings didn’t necessarily align with those in the article, the process of analyzing the data gave us a chance to critically analyze the article and consider reasons our results might not have aligned with those in the formal study. This activity fits just as well in a math, health, or science class as it does in an ELA class.

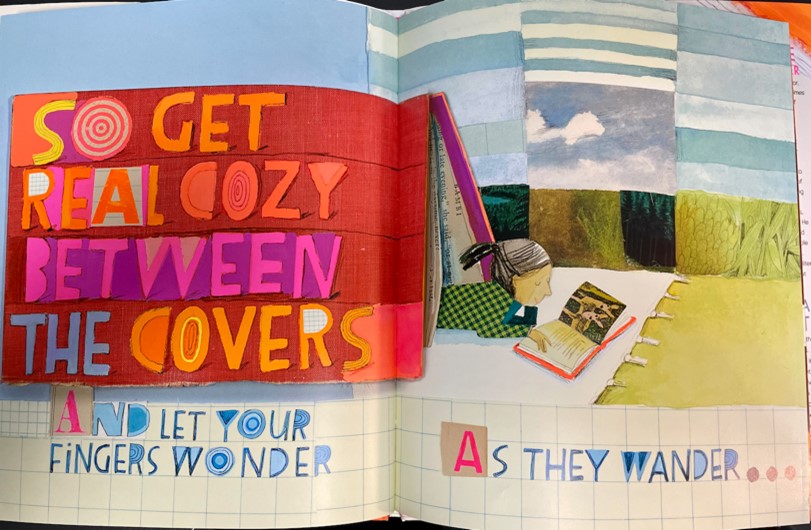

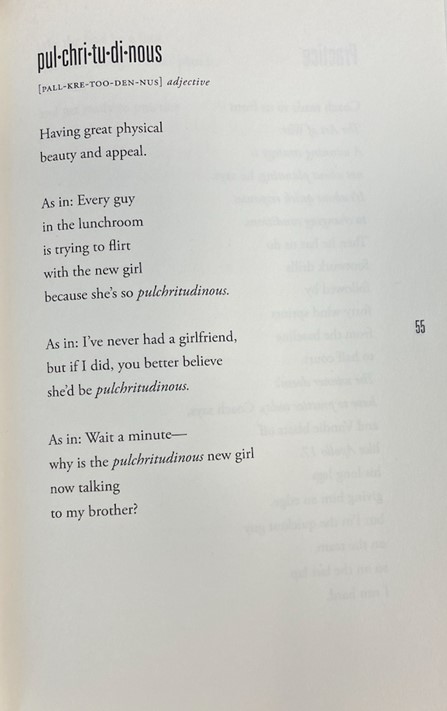

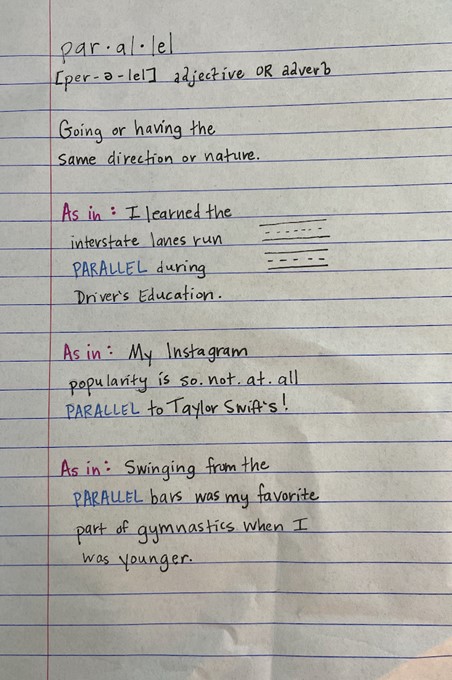

Nature Poetry

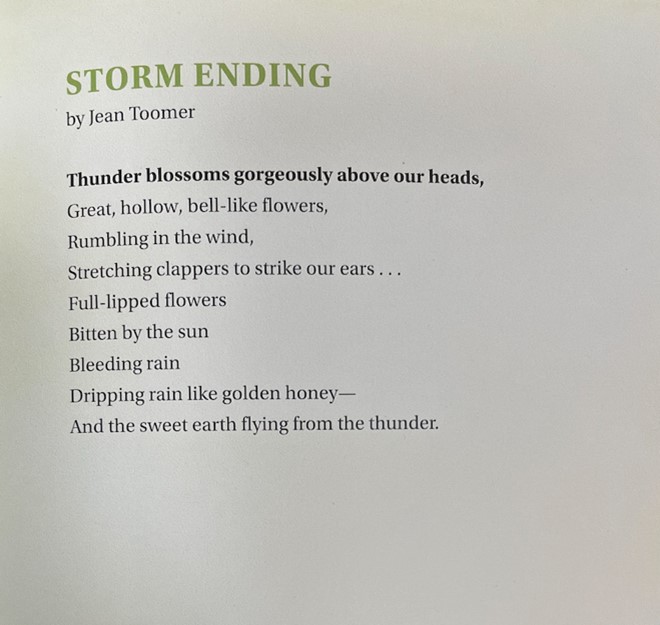

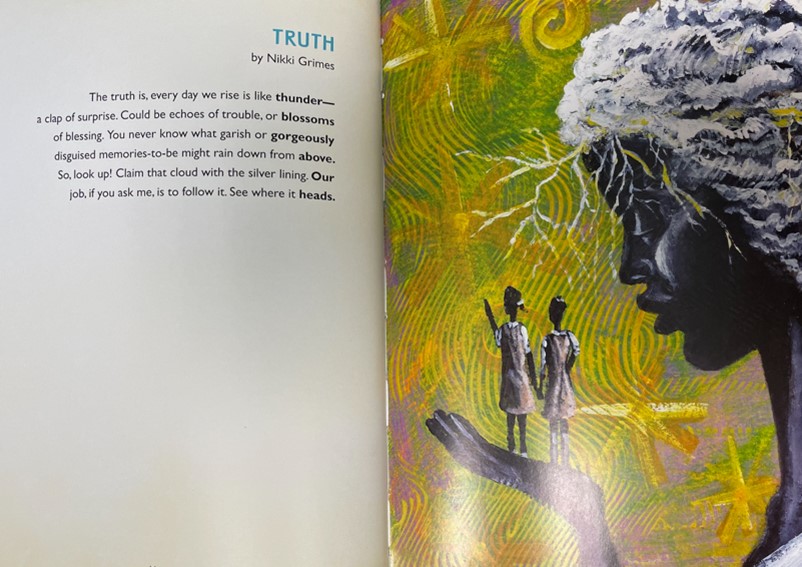

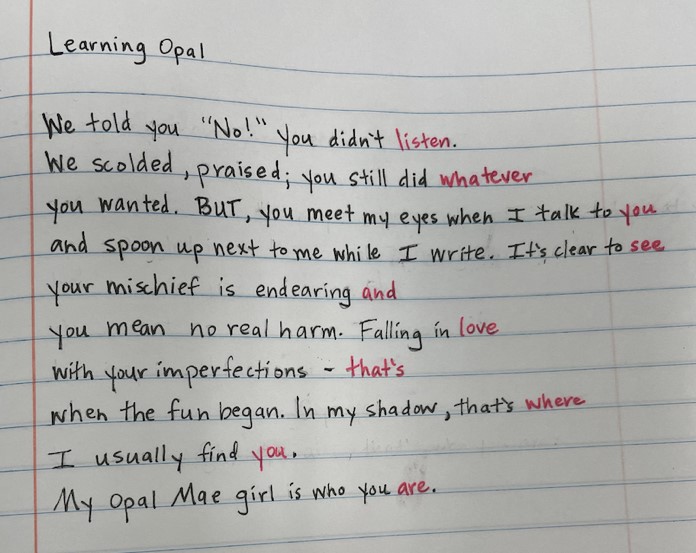

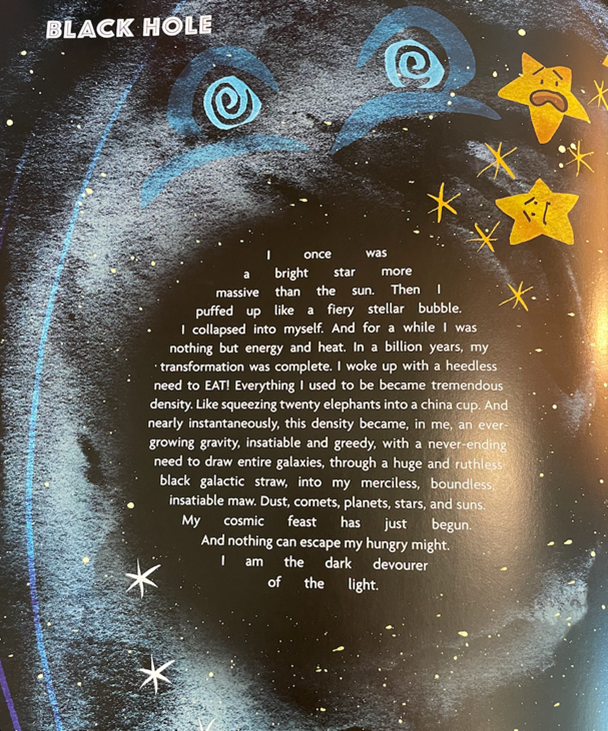

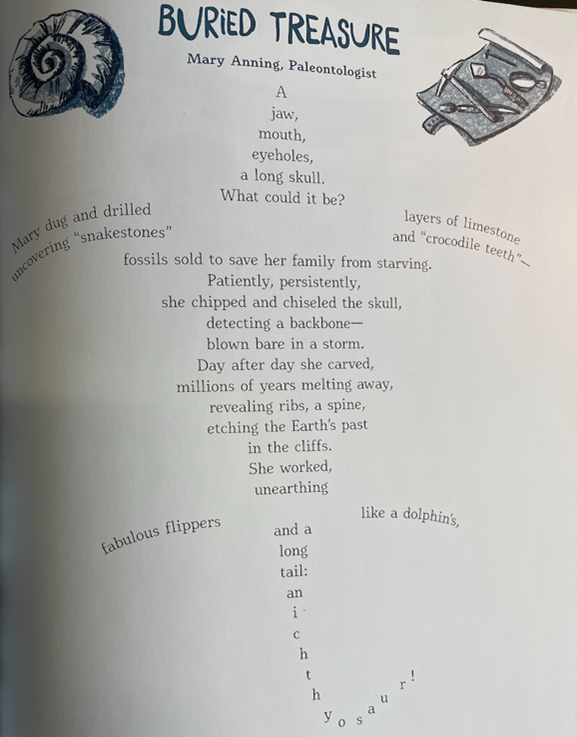

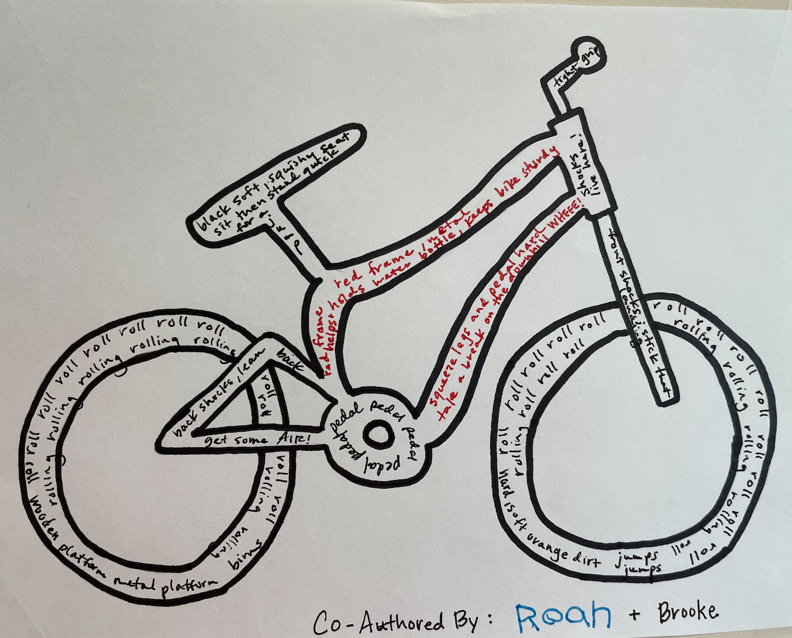

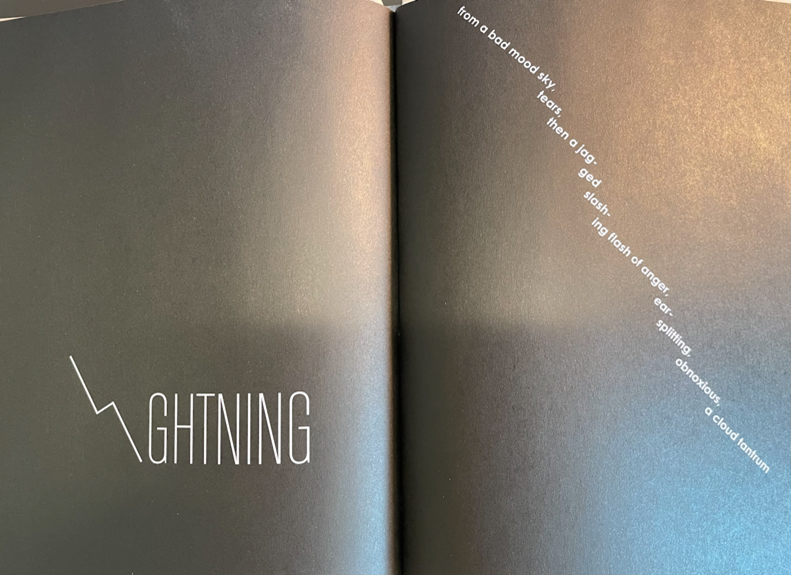

Studying mentor texts from professional nature writers provides us with a model for poetic language and symbolic representation. I include picture books as mentor texts, as well, and then encourage students to create and illustrate as they are inspired to do. Modern nature poets such as J. Drew Lanham, Ada Limón, and Aimee Nezhukumatathil provide accessible and representative poetry that inspires students to see beyond their cursory look at their school environment. Yet, students might also model scientific writing from professional naturalists and even film moments in nature following models of nature documentaries. The point is to create as professionals in the field create — whether that professional is a poet, an ornithologist, filmmaker, or a historian.

There are so many more opportunities for taking high schoolers outside for interactive learning, and the resource list I have provided here will spur many more new ideas. Regardless of the lesson, the magic of the outdoor classroom lies in students’ physical interaction with the natural environment coinciding with the shared experiences among classmates. Too often our classes seem almost virtual despite the number of bodies all sitting in a room together. Standardized curricula and mandated benchmarks tie us to screens, and the classroom itself comes with traditional expectations of what academic writing looks like and what acceptable school performance is defined as. By the time they reach their junior year in high school, many students have compartmentalized school behaviors and school literacies as quite different from their authentic lives and literacies. Too often this compartmentalizing results in stilted, perfunctory work within the classroom.

The outdoor classroom does not hold those same expectations, and without these expectations, students are free to pursue joint adventures and open themselves up to conversations and experiences. These small lessons that still fulfill requirements of curriculum standards have the potential to provide positive experiences with nature that form the affective connections later leading to activism and advocacy.

Taking students outside brings interaction with the material world, such as trees, animals, and plants, and this material engagement prepares students for self-reflective questions, such as

- How are humans connected to the natural world?

- What is my personal relationship to the natural world?

- Do others see the natural world the same way I do? Why or why not?

- What are my obligations to the natural world?

Strong memories developed through physical interaction with nature and shared experiences among classmates can be the starting point for meaningful place-based learning and environmental literacy, as Amanda taught us all when she urged us to leave our turtle in his natural habitat.

and Literacy at the University of South

Carolina (USC). A National Board Certified

Instructor, she has taught English

Language Arts at Gaffney High School in

Gaffney, SC, for 26 years. She has served

as an AP English Assesser, a National

Writing Project teacher consultant, and an

adjunct instructor with Spartanburg

Community College, Limestone University,

and USC. She shared her experiences with

outdoor learning in an article published in

English Journal in 2023, and she was

awarded a Teacher Researcher Grant

from National Council of Teachers of

English in 2024 to help fund her

dissertation study that investigates the

influence of an outdoor setting on high

school students’ writing practices.