This post is written by Brooke L. Hardin. To learn more about Brooke, please visit the bottom of this post.

What Is Concrete Poetry?

Concrete poetry, sometimes called shape poetry, is poetry whose visual appearance matches the subject of the poem. The words of the poem form a shape or shapes which illustrate the poem’s topic in visual form as well as through their literal meaning. This type of poetry has been used for thousands of years since the ancient Greeks began to enhance the meanings of their poetry by arranging their characters in visually pleasing ways back in the 3rd and 2nd Centuries BC (Nesbitt, 2023).

In the 1950s, a group of Brazilian poets known as the Noigandres developed a manifesto to define the work of concrete poetry and give us the name. The manifesto states that concrete poetry communicates its own structure: structure = content (Eppley, 2015).

How to Write Concrete Poetry

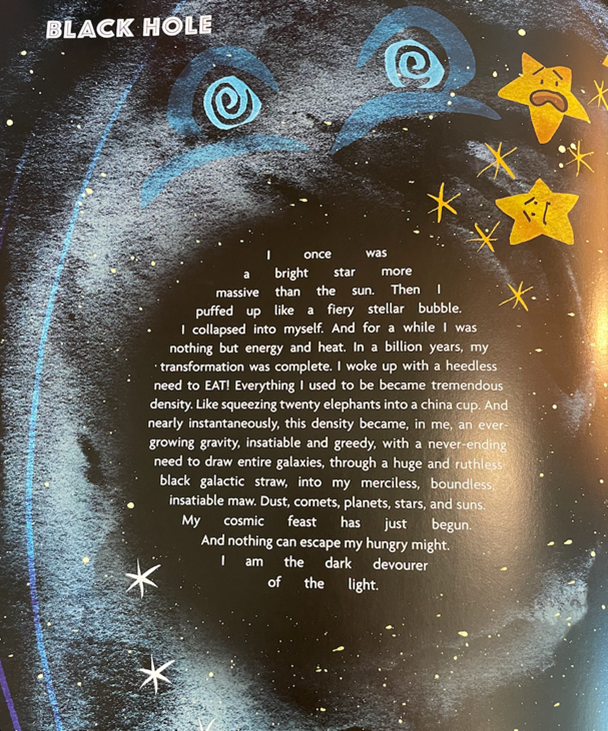

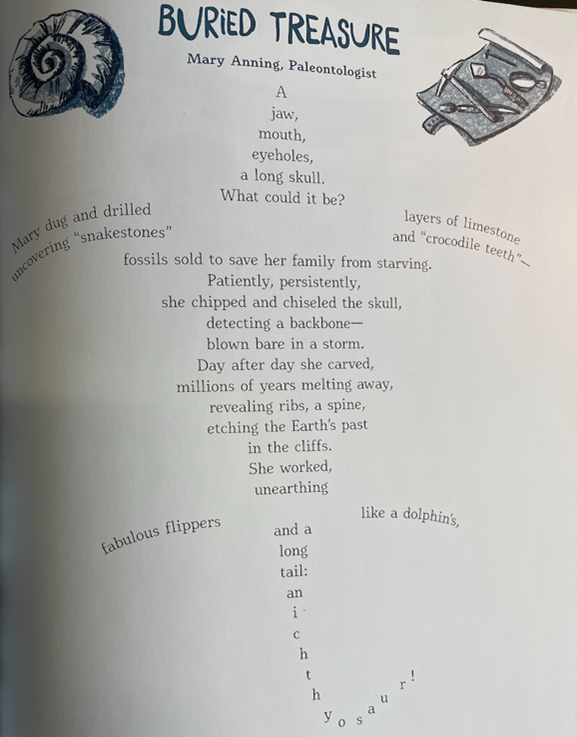

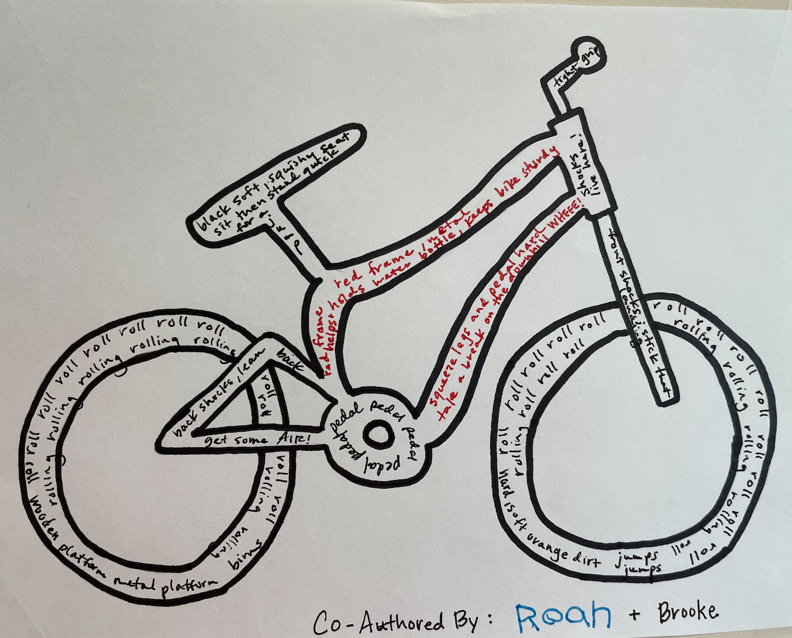

There are two main ways to create a concrete poem. The first is referred to as an “Outline Poem.” The writer creates an outline of the subject of the poem or of an object that relates to the subject and fills in the outline with words or phrases. The words or phrases used to fill in the outline usually describe the subject or how it makes the writer feel in some way, provide information connected to the subject, or possibly tell a story related to the subject. Some examples of this technique for concrete poetry are provided in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Black Hole

Note. From The Day the Universe Exploded My Head: Poems that Take You Into Space and Back Again, by Allan Wolf, 2019, Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press

Figure 2: Buried Treasure

Note. From Shaking Things Up: 14 Young Women Who Changed the World, by Susan Hood, 2018, New York, NY: HarperCollins.

My son and I recently spent an afternoon at a local bike park. Following the trip, he and I co-authored a concrete poem using the “Outline” technique. The video embedded below shows how I used questioning to help him come up with the words and phrases for the poem while I acted as a scribe. Image 3 shows the final poem we created.

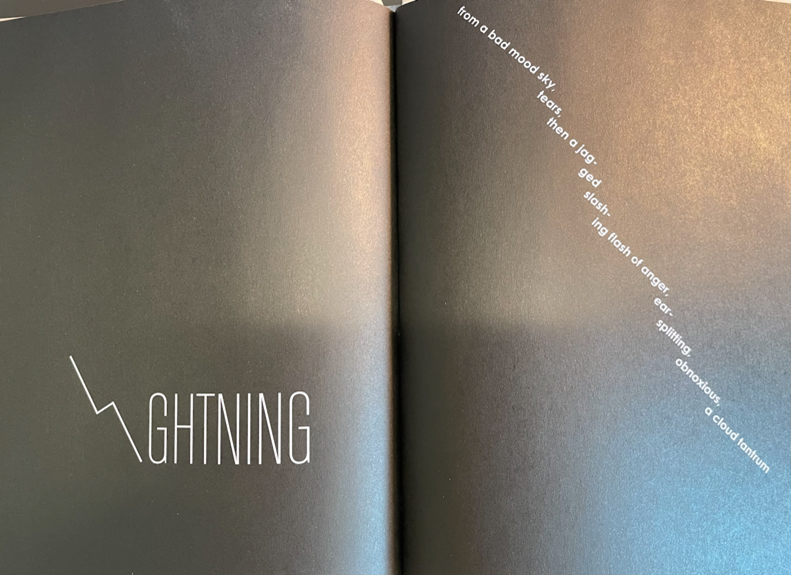

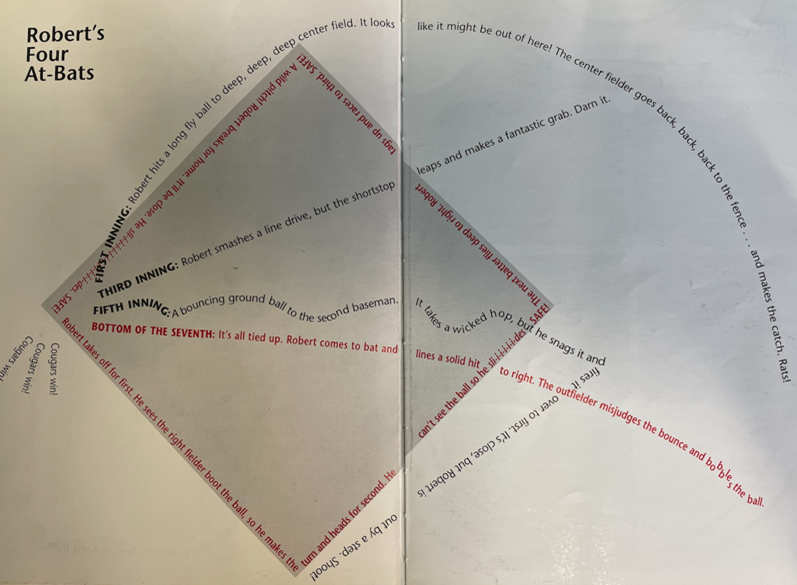

Another technique for creating concrete poems is to use the lines of words to make the lines of a drawing. One thing to note about this technique is that the subject does not have to be an object, but it does need to be something that can be drawn with “stick” figures. Examples of these poems are below.

Figure 4: Lightning

Note. From Wet Cement: A Mix of Concrete Poems, by Bob Raczka, 2016, New York, NY: Roaring Brook Press.Figure 5: Robert’s Four At-Bats

Note. From Technically, It’s Not My Fault: Concrete Poems by John Grandits, 2004, New York, NY: Clarion Books.

Instructional Considerations for Concrete Poetry

When teaching students to write concrete poems, whether using the outline or drawing technique, consider these reminders.

- Model, model, model! Planning instruction with the Gradual Release of Responsibility (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983) in mind will help students better understand the cognitive and physical aspects of composing concrete poems.

- Use inquiry to analyze some exemplars like the ones provided above or those found in books listed in the references to help students take notice of the elements of concrete poems.Select a topic as a class and write a concrete poem together, with students offering the words and their arrangement while the teacher acts as a scribe. Use questioning, such as the type seen in the video above, to help students think about their subject and form written ideas from those thoughts.Invite students to co-author a concrete poem as a pair or small group.

- Finally, provide opportunities for students to independently write concrete poems, get feedback from peers, and share their final drafts.

- Concrete poems do not need to rhyme.

- Concrete poems can be written on traditional paper or digitally. If using paper, suggest to students that they use a pencil when drafting the poems. This allows them to erase and move words around where needed.

- Encourage students to play with the size, color, and shape of their letters to better capture the essence of the poem’s subject (e.g., I might write the word TTEEEETHH in different shapes and font sizes when writing about a shark). This helps to reinforce the reciprocal nature of reading and writing by providing students a chance to consider the purpose of their craft moves.

Writing Concrete Poetry to Reflect Content Area Learning

Writing to learn and writing about learning are necessary in content-area classrooms. While many argue and I can agree that these are different notions, writing concrete poems can accomplish the aim of both.

Writing, as discussed above, must involve a discussion of ideas, leveraging the social side of learning where knowledge is co-constructed, and misunderstandings can be clarified. Additionally, when and where questions arise to inform written ideas, further research may occur; thus, more learning takes place during the writing process. For example, a student in a 7th-grade science classroom is drafting a concrete poem about a cell as part of a Life Science unit. They may refer to class notes, talk with a partner, or watch a video about cells to (1) draw the outline of a cell and/or (2) write a line about the nucleus – possibly drawing it inside another shape that is made of letters spelling out “membrane,” given that the nucleus is enclosed in a membrane. The writing of the concrete poem has the potential to reinforce learning that has occurred, provide new content, and/or inspire ways to show learning.

Both the reading and writing of concrete poems present teachers in discipline-specific classrooms with innovative methods for motivating students to engage in the content. Given their interesting appearance and brief lines, concrete poems as supplementary texts in units of study to teach a specific topic (see Image 1 about the Black Hole and Image 2 about the female paleontologist Mary Anning, who, in the early 1800s, found complete fossils that laid the foundation for Darwin’s theory of evolution) may appeal to students who are reluctant to engage with textbooks and other longer documents. As an alternative to traditional analytical research papers and essays, writing concrete poems related to learning may motivate students to take a deeper interest in the content to present their learning in a creative way. I would also maintain that crafting a line of concrete poetry deepens comprehension and calls upon sophisticated critical thinking; taking a line from prose (e.g. an article or textbook) and rewriting it in one’s own words to fit a poetic style is rigorous cognitive work. With regards to standards related to research skills and speaking and listening, I would further suggest that students provide a reference list to accompany the poems and give presentations where they explain craft moves and inspiration for certain lines.

As a former middle grades ELA/Social Studies educator, I can attest that using concrete poetry in a content area classroom allows students to reimagine learned content creatively and critically while deepening and extending their understandings and knowledge. Give it a try and share your poems with me!

References

Eppley, C. (2015, January 21). Concrete Poetry of the Noigandres, 1958-1975. Retrieved from http://avant.org/event/noigandres/

Nesbitt, K. (2023). How to Write a Concrete Poem. Retrieved from https://poetry4kids.com/lessons/how-to-write-a-concrete-poem/

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). “The Instruction of Reading Comprehension,” Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, pp. 317-344.

Children’s Literature References & More to Consider

Grandits, J. (2004). Technically it’s not my fault: Concrete poems. Clarion Books.

Grandits, J. (2007). Blue lipstick: Concrete poems. Clarion Books.

Hood, S. (2018). Shaking things up: 14 young women who changed the world. HarperCollins.

Raczka, B. (2016). Wet cement: A mix of concrete poems. Roaring Brook Press.

Wolf, A. (2019). The day the universe exploded my head: Poems to take you into space and back again. Candlewick Press.

Brooke Hardin is an Assistant Professor of Elementary Education at the University of South Carolina Upstate. Her research interests include writing development and instruction for intermediate and middle grades students, teaching and learning through technology and new literacies, literacy professional development and teacher education, and interdisciplinary approaches to reading, writing, and the utilization of Children’s Literature. Her years of experience as an elementary and middle grades classroom teacher and curriculum literacy specialist frame her research interests and commitment to teacher education.

Photo by Valentin Salja on Unsplash