This post is written by Jenelle Williams. Learn more about Jenelle at the bottom of this post.

As educators, many of us can identify mentors–people who have supported us along our educational journey. To mentor someone is both a sacred task and a tall order. In classrooms, text can serve as mentors as well. The purpose of this blog post is to clearly define what we mean by a disciplinary mentor text and to consider implications for effective disciplinary writing instruction. So let’s get started!

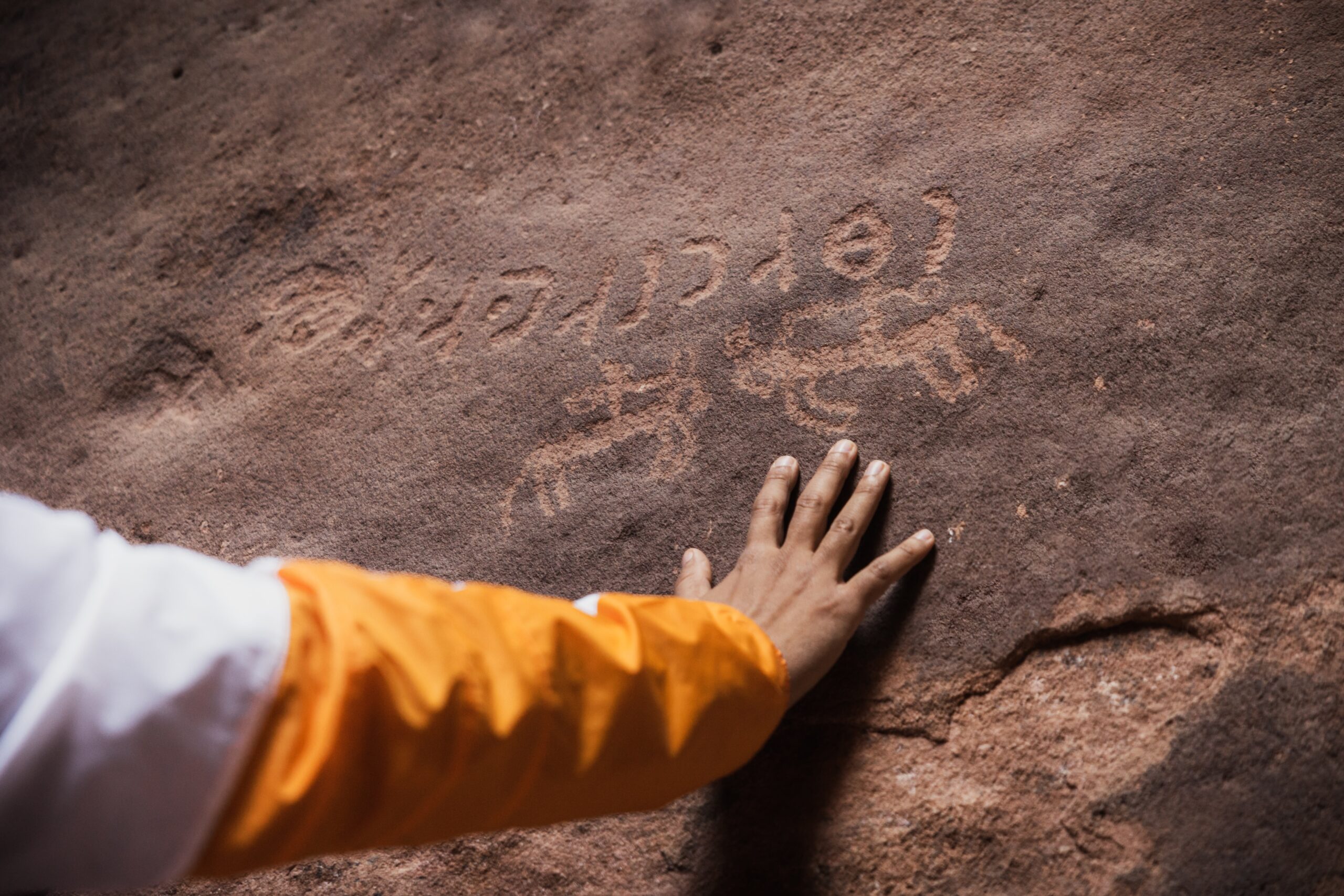

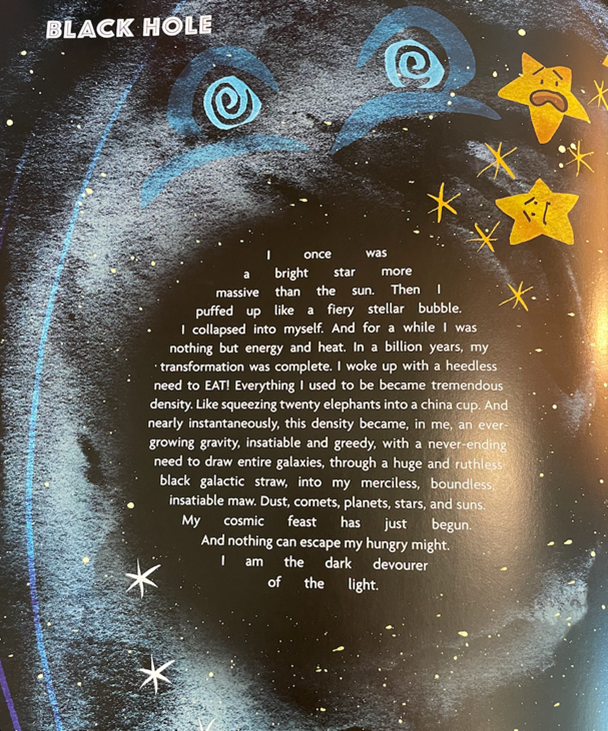

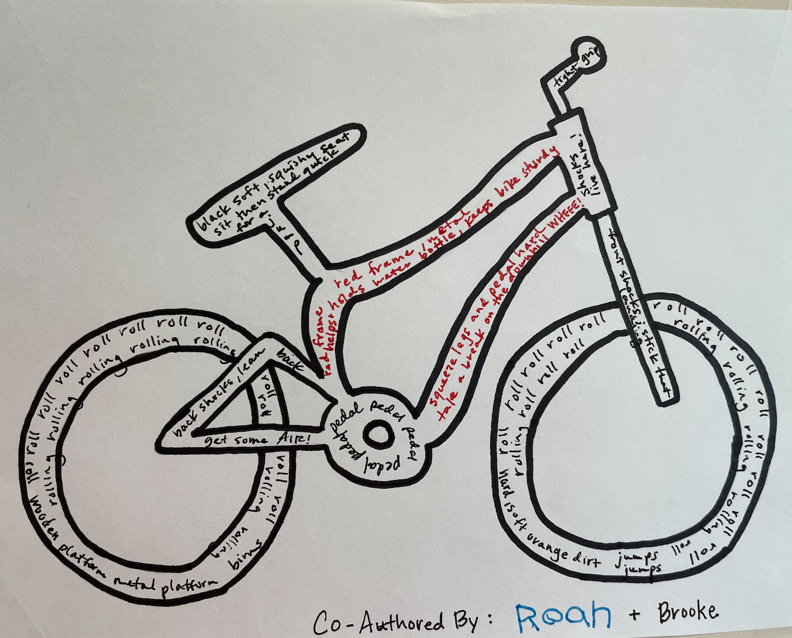

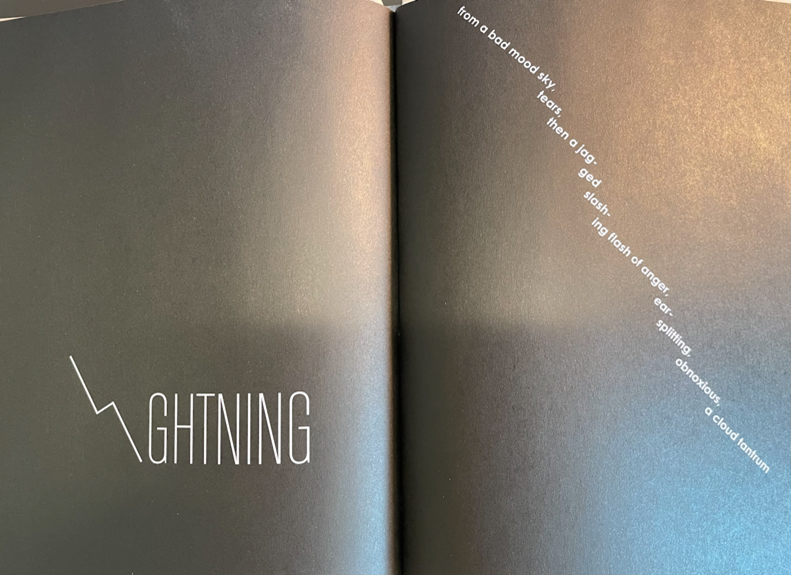

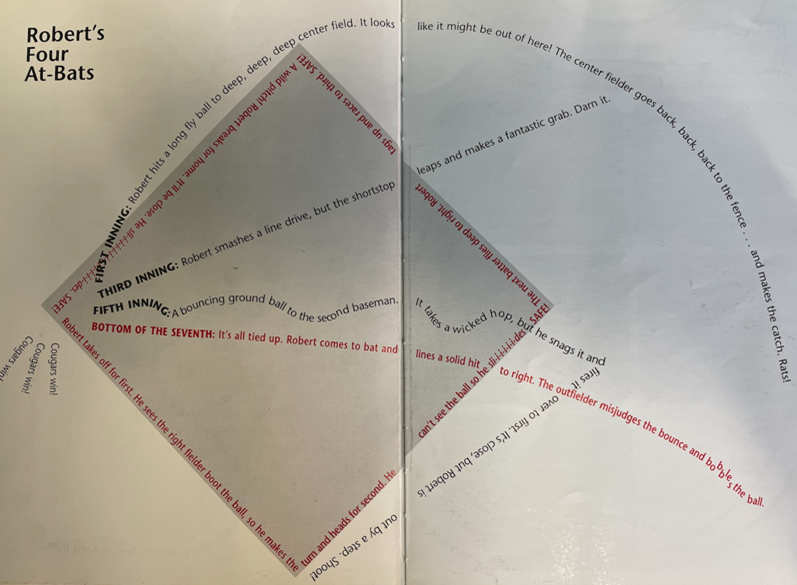

This is an exciting time to be an educator, as notions of text are expanding as time and technology move forward. For the purposes of this blog post, let’s agree that text includes anything with encoded meaning. This, of course, can mean printed words on a page, but it can also include many other things, such as symbols, musical notation, football play diagrams, dance performances, videos, audio recordings, podcasts, graphs, charts, and more. In this expanded definition of text, we must also expand our definitions of what it means to read, write, and be literate. For our purposes, being literate in a particular context means a person can consume the encoded meaning of a text, comprehend the meaning, and communicate in ways that are valued by that particular academic discipline or profession.

What is a mentor text?

Mentor texts are typically short, engaging texts provided to students for a particular purpose, including (but not limited to) the following:

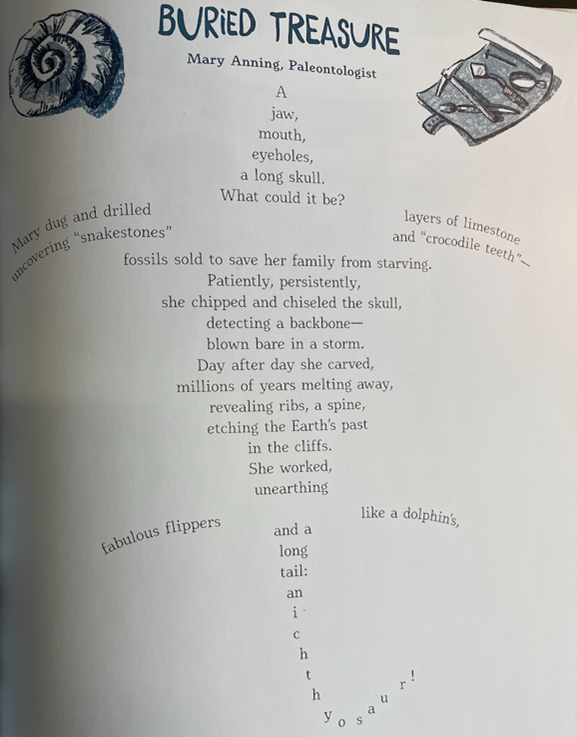

- Acting as a foundation to learn or imitate a specific writing form

- Teaching students to read with a writer’s eye (e.g., sentence structure or word choice)

- Demonstrating what good writers do

- Helping students take risks in their writing and develop their skills (from Teachstarter.com)

The role of multimodality and representation

As educators select mentor texts to use as part of instruction, it is important that, in addition to expanded notions of what qualifies as text, they intentionally include multimodal texts. Multimodal refers to something occurring or being communicated through multiple media of communication or varying forms of expression. For example, a campaign video may have images, music, text, and data all presented in one multimodal text. Students regularly interact with multimodal texts (videos with embedded audio text, for example), and need instruction and practice in order to be critical consumers of these texts.

There is an additional (and necessary) challenge as educators select texts that serve as mentors for students’ disciplinary writing–how to ensure that they are attending to issues of representation. To what extent are authors of various ethnicities, cultures, backgrounds, and perspectives represented? How might we be more intentional to include authors representing historically marginalized populations? To be sure, this requires more time and effort on the part of educators, but it is well worth the effort, as it can provide students with a connection and entry point to learning.

Authentic purpose in mentor texts for writing

In order to truly engage secondary students in authentic inquiry with mentor texts, it is vital that educators provide an authentic purpose for students to engage in mentor texts beyond simply being assigned to do so. It must be clear that the mentor text will serve a purpose and will eventually allow students to communicate their ideas with an audience greater than themselves and the teacher. The following lists some examples of authentic inquiries that would require students to engage with a wide range of texts (including mentor texts):

- Why does a lot of hail, rain, or snowfall at some times and not others?

- How can we use mathematical and statistical knowledge and analysis to monitor and predict the spread of disease and use our findings to make and evaluate decisions made at the personal, community, state, and national levels?

- How can we use poetry to promote social justice in our community?

- How can we as historians uncover and share stories about our community? Whose stories are often left untold?

Once we have identified authentic purposes for students to engage with disciplinary mentor texts for writing, we need to consider instructional approaches that leverage the power of those texts. Just as we needed to define the term “text”, it is vital that we hold a shared understanding of what we mean by the term “writing”–or, at the very least, a shared understanding of what we mean by writing instruction:

Let’s begin with some non-examples of writing instruction. They include the following:

- Writing instruction is NOT assigning writing

- It is NOT over-emphasizing grammar, spelling, and punctuation

- It is NOT requiring rigid structures (i.e. telling students exactly how many sentences, what kind of sentences, and in what order)

- It is NOT valuing the writing product over the writing process

- It is NOT copying notes from lectures or PowerPoints, definitions of vocabulary words, answers to questions straight from the textbook, or formulas for writing

When we are working with educators to strengthen their writing instruction, we emphasize the following practices:

- Modeling the process of preparing to write, drafting and revising writing, and reflecting on writing

- Using writing as a tool to support learning and reflection

- Providing support before and during writing in class

- Valuing the process of writing just as much as the product

Disciplinary writing begins with an authentic purpose for writing. Members of various academic disciplines and professions use both informal and formal writing in order to process or organize ideas; communicate and share ideas; evaluate ideas; develop and support a claim; explain a phenomenon, process, or solution; entertain; record data, evidence, and observations; solve a problem; and much more. Middle- and high-school students can be apprenticed into these types of disciplinary writing with intentional support.

For example, students in an eighth-grade Social Studies class might engage in inquiry on the following question: What was the human toll during the Civil War? As part of their inquiry, they may read the following disciplinary texts: photographs of soldiers preparing to go to war, data tables on Civil War casualties, and first-person accounts from soldiers’ diaries. Students may engage in informal writing such as annotating texts; note-taking in response to readings, discussions, or teacher-presented information; and constructing an outline and then a first draft of a historical account or explanation. Formal writing may be a historical account or evidence-based argument about the human toll of the Civil War that is shared with an appropriate audience beyond the teacher.

Essential Instructional Practice 4 & additional helpful resources

Essential Instructional Practice 4 from the Essential Instructional Practices in Disciplinary Literacy document is a great place to start for teachers that are interested in strengthening their support of students’ disciplinary writing. Teachers may read the General Practices at the beginning of the document, or they may be interested in selecting the content area section that best aligns with their work. Additional helpful resources are also suggested in the table below.

| Multidisciplinary | |||

| Learner Variability Navigator | |||

| ELA | Mathematics | Science | Social Studies |

| Michigan Middle School English Language Arts Units | Writing in Mathematics – Annenberg Learner | Scaffolding Students’ Written Explanations | AST Beyond Writing to Learn, The Science Teacher (NSTA) | Read.Inquire.Write |

| The New York Times MS HS Writing Curriculum | |||

| Music | Physical Education & Health | Visual Arts | Heritage & World Languages |

| Lesson Idea | MAEIA | WritingAthletes.com | Lesson Idea | MAEIA | The Nature of L2 Writing | Foreign Language Teaching Methods |

The great news is that secondary educators do not have to be writing experts (or even published authors) in order to teach students how to write effectively within and across disciplines. As long as we keep expanded notions of text, multimodality, and representation in mind, along with an authentic purpose for students to engage with a disciplinary mentor text, we are well on our way to modeling and scaffolding students as they create disciplinary texts of their own. We are lucky as well that we have free, widely available resources that can help us shift toward effective pedagogical moves. Let’s get writing, everyone!

Jenelle Williams is a Literacy Consultant within the Leadership and Continuous Improvement unit at Oakland Schools, an intermediate school district supporting the 28 districts in Oakland County, Michigan. She joined the organization in 2017 following 18 years of experience in public schools at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. She has served as a classroom teacher, IB Middle Years Programme Coordinator, teacher leader, and educational technology coach. An IB Educator and Examiner since 2013, Jenelle leads professional learning workshops and marks e-assessments for the International Baccalaureate Organization. She holds an Education Specialist in Leadership degree and a Master’s degree in Reading and Language Arts through Oakland University. In addition, Jenelle serves as an Adjunct Professor in Grand Valley State University’s Graduate Program and a co-editor of The Michigan Reading Journal, a publication from the Michigan Reading Association. Jenelle is passionate about supporting teachers, building leaders, and central office administrators in the area of secondary literacy, and she is especially excited to be able to support Michigan’s work around disciplinary literacy through her role as Co-Chair of the statewide Disciplinary Literacy Task Force. She can be reached at jenelle.williams@oakland.k12.mi.us, and on Twitter at @JenelleWilliam6 and @GELN612Literacy.

Cover Photo by Desola Lanre-Ologun on Unsplash