Classroom teacher Wanda Littlejohn shares how she engages striving readers using the Jigsaw Strategy. Read more about Wanda at the end of the blog.

My classroom teaching experience began over 20 years ago in an affluent school district where there were only a few elementary schools, two middle schools, and one high school. All of the schools focused on student academic growth and excellence, and they collaborated well together to ensure the content taught was aligned vertically and horizontally. Most of my students read fluently, were motivated to learn new things, and had similar experiences at home and at school. As a science teacher, I rarely had to provide interventions to gain student interest or to help them read and write like scientists. However, over the years I have learned that my experience as a classroom teacher is vastly different and not all students make it to high school knowing how to read and write fluently. According to the 2023 SC Ready test results, only 53% of eighth grade students either met or exceeded the reading expectations for the state while other subgroups such as pupils who are in poverty, Black, multilingual learners, and with disabilities performed at a rate of 42.3% or less (SCSDE, 2023). Because of these results, it is evident that students entering high school need reading support, and high school teachers need to be equipped with strategies that will assist students in all content areas, specifically in science. In this post, I will share how I utilized the jigsaw strategy as a means to facilitate success for striving readers a biology class.

In the January 4, 2022, issue of EdWeek Madeline Will states: “For the millions of students who struggle to read at grade level, every school day can bring feelings of anxiety, frustration, and shame” (p.1). The highly rigorous curricular standards outlining the knowledge and skills students should have by the end of each science course are designed to prepare students to predict outcomes, create procedures, analyze data, and draw conclusions. If over half of the students entering high school are unable to read at grade level, they are not able to meet the science classroom demands, ultimately leading to students’ feeling frustrated and lost in their science classes. Will (2022) goes on to state “…children who don’t receive appropriate support can fall behind in multiple classes, even though they are capable of intellectually understanding the material” (p. 2). If students are intellectually capable of understanding the material, scaffolds need to be put in place to bring that intellectual understanding out of them. Moreover, those strategies need to assist the striving reader’s comprehension of scientific text and vocabulary.

I had the pleasure of providing corrective instruction for several groups of students taking a Biology I course, many of whom were either multilingual learners or were students with a learning disability. During the lesson, we addressed the processes of cell division, cellular respiration, and photosynthesis and their importance to sustaining life. Because these concepts are so abstract, many students find them difficult to grasp. The teacher’s initial testing showed these students needed more time with the content because they were unable to clearly define the concepts or processes which had been taught nor were they able to identify models that represented each concept. It was evident from these data that students needed a way to better comprehend the vocabulary.

Addressing the concern of providing appropriate support for striving readers, I chose to use the jigsaw strategy to support these learners as we revisited the concepts stated above. In John Hattie’s research, the jigsaw strategy has a large effect on student achievement. Hattie proclaims in his book Visible Learning (2009) that self-instruction, organizing, and transforming are valuable tools to get students to be active in their learning and all create a high impact on student growth and achievement. The jigsaw strategy adds student discourse to the lesson and allows students to read, write, speak, and listen within a cooperative setting.

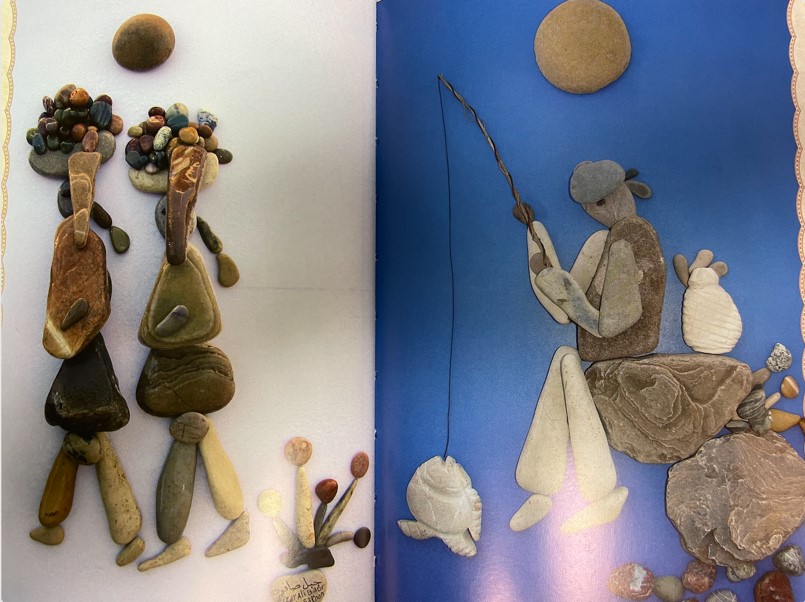

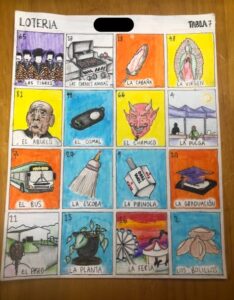

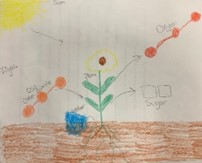

During the lesson, the students were assigned one of the four concepts (photosynthesis, cellular respiration, macromolecules, cell division). The students were given 20 minutes to read articles and listen to videos about their assigned topic. Each student was given a graphic organizer that supported their reading and listening and contained questions they had to answer during their individual research time to ensure they were obtaining the right information about their concepts. After their research phase was complete, the students were given 30 minutes to work in expert groups with other students who had the same concept so they could synthesize and organize their information. The students also had to create a model representing their concept and produce talking points they could use to explain their concept to others. It was imperative for me to conference with each group during the expert phase to ensure they were on the right track and they had accurate descriptions. The final step in the process was to jigsaw the students so each group contained an expert on each concept. During this phase, the students shared their models, while other students filled out a graphic organizer capturing the new information learned. As the jigsaw ended, one student indicated she really felt better about the concepts and she learned so much in the smaller group setting. At the close of the lesson, the students took a short assessment again on each concept.

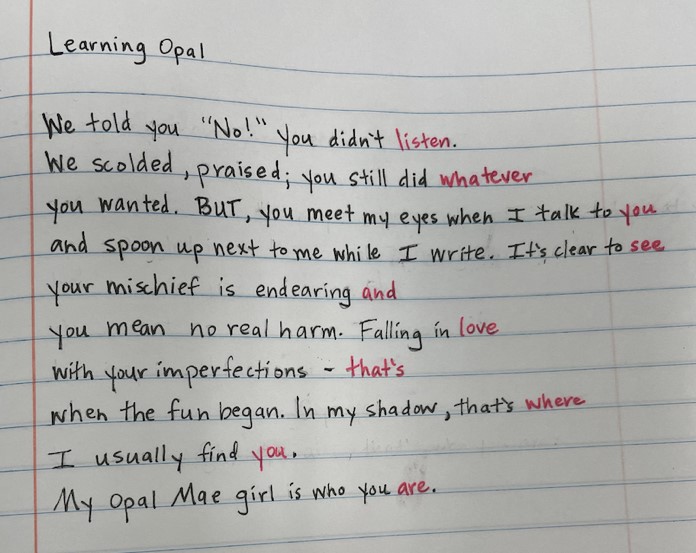

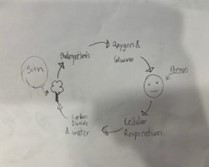

In Biology, the standards require students to create models to illustrate the processes of both cellular respiration and photosynthesis. The figures above show some of the students’ interpretations of those process after completing the jigsaw activity. It was evident from the figures above that the students had a general understanding of both processes. Figure 2 shows an even deeper understanding that both processes depend on each other and produce a continuous cycle.

In closing, striving readers, according to Will (2022), need a supportive classroom environment where they are welcomed to be risk takers and to have a growth mindset. During a jigsaw activity, there are a lot of moving parts and directions. The advice I would share is to be prepared to redirect students, repeat instructions, and visit each individual during each phase to ensure the students feel supported. Allowing students to research and read individually first gives them an opportunity to make meaning of things before they have to make meaning with a peer. Becoming an expert with a peer allows striving readers to reread and repeat information a second time, which enhances comprehension. I found the jigsaw strategy increased student knowledge of the concepts, gave them the confidence they needed to engage in discussion with their peers, and gave them the ability to complete the models shown in Figures 1 and 2. To learn more about the jigsaw strategy, click here.