By: James Campbell, South Carolina High School Spanish Teacher

Students were arriving to their first day of AP Spanish class, some timid and some visibly relieved to be in a familiar classroom. Many had taken a Spanish-for-heritage-learners’ course with me, most had experienced being in a Spanish class designed for students well below their proficiency level. We discussed their academic experiences a little to start the short semester. We all listened quietly while students took turns telling stories about how they were called “cheaters” for knowing Spanish already, how they had all been approached to “share” their work with other students, how other students were surprised that they could speak English, and how they were always tasked with the “Spanish part” of any collaborative project they were doing. After hearing them describe the antiquated academic requirements in a system not designed for them, I stared blankly over the silent classroom into the painting on the back wall. “We should go over the syllabus,” I thought. “We only have a few months before the exam and we have a lot to cover,” but I just couldn’t get myself to say it out loud. One student said, “Well, those students aren’t going to get college credit for knowing Spanish,” keenly aware of the irony. “When are we going to play Lotería?” we heard from a quiet student in the center of the room. The room exploded with excitement.

The Original Game

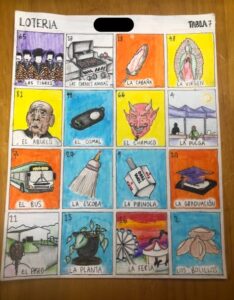

Lotería is a bingo-like game with images that represent different elements of traditional Mexican culture, though the game is not only played in Mexico. I am not Mexican or Hispanic but I love seeing the nostalgic mood rush over many of my Spanish-speaking students who almost hum hearing the short verses on the back of each card, who argue over how to play according to their family’s reglas, and who have memorized an entire tabla (a 4 x 4 grid on which the game is played). It is a great listening game with the entire room silent until someone calls out “¡Lotería!” with a full tabla. It is an authentic game that everyone can play. It does, however, have some problematic elements.

One day, after one of my Spanish 3 Honors students asked, “Are we going to play that racist bingo game again?” I thought more about the disclaimer I give about some of the images in the game. I never tried to explain them away but challenged them to research where they came from and how they ended up in the game. I discussed this some more with my AP students that next period, and it hit us almost simultaneously – we should update some of the images for our classes.

The New Game

So, we began our year-long journey to re-imagine a highly recognizable piece of Mexican culture. As with any project that begins as organically as this, their trajectory almost immediately began to shift from changing just a few of the images on the board to a weeks-long brainstorm on reimaging the entire gameboard to represent the diverse Hispanic experiences in the Upstate of South Carolina. The students drew from a seemingly endless mental library of personal and familial experiences to create a list of over 200 people, animals, places, foods, clothing items, and more. The students, from different parts of the Spanish-speaking world, began to see how similar some of their experiences were as Hispanic students and how unique they all were at the same time, not just the stereotypes others had for them or that they might have had of each other. After much discussion and debate, the students were able to reduce their ideas to the standard 54 images, which they divided amongst themselves. Each student produced a visual concept and a catchy phrase, poem, or quote for their peer-assigned tarjetas.

They then presented them to the class, one-by-one, each fielding questions and feedback from their critical peers. The students took the feedback seriously, not personally. Our classroom artists decided on a cohesive theme for the boards. Our creative writers went to work rewording some of their classmates’ verses on the back of the cards. Other students spent time making sure not to repeat the reason they started this whole thing and took votes on replacing some that may unintentionally perpetuate unhealthy stereotypes of themselves. They spent the last 20-30 minutes of each 90-minute class in a buzz of “do this,” “don’t forget to mention that,” “should we add this?” and “who was in charge of these?” completely owning what would become a way to tell the story of their community. I, their teacher, had become a giddy observer, fully convinced that they could produce and distribute their version of this game to the community.

In what I can only describe as a completely serendipitous moment, I ran across a painting done by an artist in South Carolina that told the story of an immigrant girl in the format of a Lotería tabla. It was a moving piece with an even more incredible story behind it. I talked to the artist and set up a visit for later that month. In the meantime, I showed my students the painting, at which time they immediately wanted to drop everything and make their own. “Working together is just too exhausting,” one said. After a couple apologies and recommitments, everyone was back on board. A week later was our last day of the semester together due to COVID-19 (I just checked, and the Google Doc we were working on was last edited on March 13, 2020). The biggest and most exciting project that my students had ever come up with was over. Or so I thought.

After a few weeks of figuring out eLearning and doing what we could to prepare for who-knows-what the AP test would look like, we had our first virtual class meeting. After getting updates from everyone and going over their virtual assignments they all wanted to know what would become of their Lotería project. Not wanting to stress students out any more than I needed, I sadly told them I had no plans to continue it collaboratively but they were welcome to continue it on their own. “It’s just too hard to facilitate such a big project together right now,” I said. Then, without hesitation, a student suggested they all make their own board, “You know. Like that artist did”.

The Final Product

Over the last two months of the semester, as the students prepared for an abridged AP Spanish exam, they drew, took pictures, wrote reflections, and all designed a tabla that told the story of their own journey of how they got to where they are now. During this time, we hosted virtual visits with Hispanic community members, writers, artists, and teachers from across the Carolinas. The students’ voices grew more confident with each new guest and, since I got to hear them repeat their stories multiple times, I noticed them embracing images that told stories of deep, personal sorrow and joy. Their classmates noticed this too. One of my younger students, in tears, shared at the end of the course how glad he was to be a part of listening to his classmates’ stories even when he wasn’t as comfortable sharing his at first because he thought it wasn’t as cool as the others’. “No, no, no,” an older classmate chimed in, “we couldn’t have done it without you.”

I think about this project almost every day. Even though they all designed and presented individual products, there was a sense that this was a complete group effort, even in its final iteration. It makes me wonder how I could ever again do a project in my class where a student says (or even thinks!), “we couldn’t have done it without you” at the end of it to another student. But, I know that something like this will never happen again if I can’t learn to listen to and trust students. It won’t happen again if I don’t find space in my curriculum for students to find their voice. And, students will never have as big an impact on each other’s learning and emotional well-being as they did with their Lotería boards if they don’t feel safe enough to share their voice. They did this and proved this together and I couldn’t have done it without them.

About the Author

James is in his 14th year as a Spanish teacher and is the 2020-21 Teacher of the Year at Carolina High School.