This post is written by Erin Kessel. You can learn more about Erin at the bottom of this post.

What is a literacy leader? In my opinion, it is a highly qualified teacher in literacy instruction who provides valuable resources for other teachers to facilitate quality instruction. Providing highly qualified teachers with the opportunity to fill this role promotes growth in our field, allows these experienced teachers to stay in the classroom, and gives more novice teachers a mentor to support them. Today I will share with you my personal story as a literacy leader and the opportunities it provided me to grow as an educator while also growing others.

In 2020 I was offered an opportunity by my district to become a Multi-Classroom Teacher with a focus on literacy. The Multi-Classroom Teacher position was created in our district for master teachers, a designation determined by classroom observation and student performance data, who then co-taught across multiple classrooms with other teachers and apprenticed them in highly effective instruction. After 12 years in the classroom, mentoring beginning teachers, supervising interns, and leading PLCs, I was ready to grow as an educator and accepted the position. The goal was simple — mentor and model literacy instruction in five 3rd through 5th-grade classrooms where teachers had less than three years of teaching experience.

Through years of learning and applying strategies of Adaptive Schools and Cognitive Coaching, I began with a plan to actively listen to the teachers, identify needs, and establish goals to support them. I spent two weeks simply observing the literacy blocks of each classroom. I recorded objective, anecdotal notes and began to set my intentions for areas of targeted support with each teacher. The following descriptions are the focus areas based on my data for each teacher:

- Teacher #1 – An experienced teacher assistant transitioning to a teacher with strong small group instruction skills but difficulty designing whole group literacy instruction where students experience a gradual release of responsibility of learning (Goal – To design whole group literacy lessons focused on scaffolding the learning for students).

- Teacher #2 – A engaging third-year teacher who had powerful literacy instruction methods but lacked knowledge of how to incorporate collaborative learning within her classroom (Goal – To learn about, model, and engage in collaborative strategies).

- Teacher #3 – A second-year teacher who had the “right stuff” as an educator but had never taken the time to build rapport with her students and felt a lack of community within her classroom (Goal – To build relationships with and learn about students as people including their likes, interests, and home life).

- Teacher #4 – A compassionate second-year teacher who lacked organization and engagement strategies to encourage her students to want to learn (Goal – To learn about, model, and engage in Whole Brain Teaching strategies).

- Teacher #5 – A first-year teacher who spent her clinical teaching year virtually due to COVID who lacked sufficient classroom management skills, therefore behaviors and disruptions were consistently affecting learning (Goal – To establish norms and routines in her classroom as well as create a concrete classroom management plan to hold students accountable of their actions and encourage them to want to learn).

After a week of collecting observational data, I set a time to meet with each teacher and have a goal-planning conversation. Within the Cognitive Coaching model, it is the coach’s job to lead the participant/s through the stages of a conversation where they identify their goals and set their own plan while the coach provides some potential strategies. I discovered this group had not been able to collaborate with an experienced teacher since their student teaching and therefore did not have access to guidance, resources, and tools for effective literacy instruction.

As a mentor teacher, I had the experience, knowledge, and resources to support each of these teachers’ goals. I asked the teachers to become observers for two weeks during their literacy block and allow me to facilitate learning in their classrooms while focusing on their specific needs. The teachers used an observer form to stay focused on my facilitation of the instruction specifically tied to their goals. I also attended their planning periods, where we collaborated to develop a library of lessons and resources. I built rapport and trust with each teacher, which allowed us to consistently hold reflective conversations focused on their goals and ways to incorporate the instruction they observed into the lesson plans we created.

(When these amazing teachers choose to dress in my Erin Kessel “iconic” daily outfit, I know I have made connections with my teachers)

I spent two weeks cultivating and facilitating different plans for each class and working with students of all ability levels while incorporating many diverse types of teaching strategies to model options of literacy learning. The following were ways I helped each teacher approach her goal:

- Teacher #1 – We redesigned her schedule with a specific time set to introduce content, model, and allow students to practice and apply their learning. We also planned — and I modeled — how to provide differentiated opportunities in a lesson during whole-group instruction. We developed a presentation format (PowerPoint) for her lessons that guided her through the gradual release process.

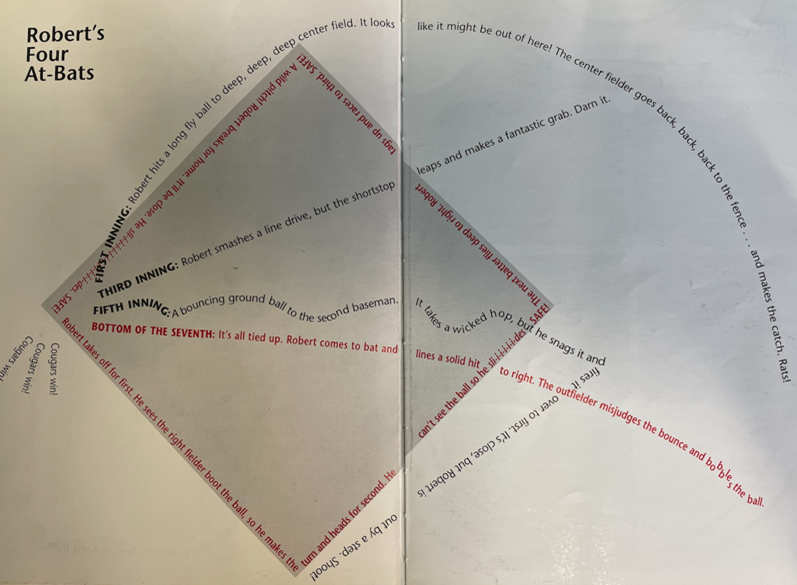

- Teacher #2 – I intentionally introduced the class to collaboration practices and strategies within the literacy block. Students participated in Learning-Focused Collaborative Pairs, Socratic methods of teaching, Kagan Cooperative Learning strategies, Adaptive School strategies, and other various strategies I have created through my own experiences. As this teacher observed these strategies being applied in her classroom, she saw student engagement increase, students’ understanding of content grow, and more students involved in class discussion. She then utilized the strategies she was seeing modeled.

- Teacher #3 – Community meetings were established each morning before her literacy block, which engaged students with each other and utilized multimodal methods of literacy to prepare their brains for the day. Multiple community meeting processes were used where students expressed themselves as individuals and learned commonalities with each other. The teacher participated and learned about the students as individuals, and the students learned more about the teacher. The rapport became evident when students began to support each other during collaborative activities. They also entrusted the teacher with more personal information and would seek guidance in non-academic situations.

- Teacher #4 – Through modeling and professional development of Whole Brain Teaching, she was quickly able to establish daily routines through fun callbacks, engage in bodily-kinesthetic and verbal learning of literacy curriculum, and create a respect for her attention when deemed necessary. Her classroom management, routines, and classroom literacy instruction benefited from utilizing this program.

- Teacher #5 – Through consistent use of expectations and norms and a structured schedule, the teacher replicated my modeled methods and saw improvement in the respect her students had for her. Through attending the planning periods, asking questions, requesting modeling of instruction, and assisting in designing literacy assessments, her understanding of literacy curriculum and how to facilitate it increased exponentially. She also benefited from the shared PowerPoint presentations we made during planning to guide her instruction.

After teaching in all classrooms, I began to see the value of my effort. I started noting strategies I used in their literacy blocks were now being used in other core content areas by these teachers. When we met to review our planning conversations, some teachers felt they had met their goal, and through planning conversations, we established new goals. Over the course of two years, I co-taught and co-planned with these teachers.

(As the shirts state, “Together through it all” was our motto as we worked side by side in their classroom every day.)

The experiences I had as a Multi Classroom Teacher and literacy leader within this school began to grow my need to share this role with others. I recently became a teaching instructor at East Carolina University, where I teach the READ courses to education major students. I can share my experiences and grow our future teachers as they explore their concentrations for their education degree. I encourage students to explore our Read Concentration program to help develop our next Literacy Leaders. I have spoken at multiple conferences on the value of literacy leaders and continue to speak on the benefits of this role in every school, especially schools with low teacher retention rates, as that is where they are most valuable and can make the greatest impact.

Erin Kessel is a teaching instructor in the Literacy Studies, English Education, and History Education Department at East Carolina University. Previously, she was a Multi Classroom Literacy Leader, Facilitating Teacher, and a 4th grade teacher. Erin’s work focuses on literacy leadership and developing literacy leaders as well as building a classroom community through literacy as she presents at the local, state and national level.Follow on Twitter @kessel_erin

Please cite this work: Kessel, E. (2023). Growing as a Literacy Leader. Literacy In The Disciplines. https://literacy6-12.org/growing-as-a-literacy-leader. CC BY 4.0 license.

Cover Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash