This post is written by Michael Manderino. You can learn more about Michael at the bottom of this post.

“We cannot remake the world through schooling, but we can instantiate a vision through pedagogy that creates in microcosm a transformed set of relationships and possibilities for social futures, a vision that is lived in schools. This might involve activities such as simulating work relations of collaboration, commitment, and creative involvement; using the school as a site for mass media access and learning; reclaiming the public space of school citizenship for diverse communities and discourses; and creating communities of learners that are diverse and respectful of the autonomy of lifeworlds.”

New London Group, 1996

It often amazes me how prescient the text (quoted above), A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures (1996) was and what it argued for just before the dawn of the 21st century. Now in the year 2023, using terms like 21st-century learning doesn’t resonate much as we are nearly a quarter way into the 21st century. I often question how much we have really taken up from the ideas even extracted from the quote above. While disciplinary literacies have been at the forefront of theory and research around adolescent learning, I believe that we need a future vision of the possibilities of disciplinary literacy. We need more than practices that simply reproduce knowledge. We need an expansive theorizing of what disciplinary literacies can be or else we will continue to reinscribe old ways of knowing and doing for a future that is yet to be written.

Despite a need for a widening of thought, we collectively find ourselves presented with seemingly predefined choices for where we need to stand pedagogically. Dialogues have shifted to debates over everything from the “Science of Reading vs. Balanced literacy, Online reading vs. Offline reading, or the use of the canon vs contemporary fiction. The pitting of the pedagogical constructs against one another creates a reductionist view of the complexities of teaching and learning. Rather than reducing complex pedagogical constructs to binaries, perhaps we should be interrogating the possibilities for pedagogical expansion. While simple answers feel more reassuring, they do not account for the beautiful complexity of teaching and learning.

One reductionist view we might interrogate is the narrowing of what counts as disciplinary inquiry. Expert novice studies have provided invaluable insights into what are core disciplinary practices yet can often be taken up as the singular way to approach disciplinary literacy. Disciplinary literacy in its early conceptualization offered new ways to think about advancing knowledge building in content-area classrooms. What follows is a set of possibilities for consideration of what might be taken up in research and practice around disciplinary literacies. Using the metaphors of pathways, prisms, and portals, I argue for the use of multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary approaches in disciplinary inquiry.

Pathways

Disciplinary literacies can be pathways to explore through multidisciplinary perspectives. Pathways can be paved, worn by repeated traffic; serve as shortcuts or trails that lead to hidden beauty. Pathways can diverge or converge. People use pathways to get somewhere or to meander. Sometimes along the path, new discoveries are made, or new paths are forged. Pathways can serve as a metaphor for multidisciplinary inquiry. One may choose to look at a problem or topic from the lens of different disciplines. Like choosing a path or multiple pathways, inquiry can be shaped by one, two, or more disciplines. While it is critical to understand the beliefs, practices, texts, and tools used in a discipline like science or history, it is also important to see that inquiry questions can be approached from multiple disciplines. For example, we can look at a problem such as food scarcity from the perspectives of geography, economics, agriculture, and mathematics, to name just a few. We need to engage with the world from multiple perspectives that are often shaped across disciplines. Food scarcity is not a simple problem that can be understood or tackled from singular perspectives. If we only hyperfocus on singular disciplines, we may lose the forest through the trees.

Prisms

Disciplinary literacies can also be prisms for seeing new possibilities. Using singular lenses to problem solve or problem pose does not account for the complexity of the problem. Prisms can reflect and refract light to illuminate the full spectrum of colors that are being absorbed. Prisms help us see things in a new light. We can think of interdisciplinary inquiry as a tool for seeing the full spectrum of perspectives around topics and problems. Interdisciplinary inquiry relies on the interconnected nature of disciplinary practices and perspectives. If we expand notions of disciplinary literacy to interdisciplinary, we add the nuances of the comparative and contrastive beliefs, tools, texts, and approaches to understanding phenomena. For example, the role of art, music, and literature provides indispensable insights into complex phenomena that cannot be fully explained through a historical or scientific analysis. By using interdisciplinary inquiry as a prism, students have access to new ways of seeing the world and their role in the world.

Portals

Disciplinary literacies can serve as portals to newly designed futures. During the Covid-19 pandemic, author Arunduti Roy (2020) argued that the pandemic could serve as a portal to new social possibilities. The notion of portals to new dimensions or time/space scales is one that is speculative and hopeful. To see disciplinary literacy as opening portals to solving wicked problems to create more just worlds is a goal that makes learning consequential. Portals also lead to the unknown. Much like disciplines themselves, portals are unsettled terrain and are absent critical voices who are often erased or silenced. To account for these silences and erasures, transdisciplinary research is conceptualized as a way to be inclusive of multiple perspectives not simply from the top down (academia) but also from the ground up (lived experiences). A transdisciplinary approach to inquiry opens opportunities for problem-posing and solving that values indigenous and local knowledge and its relation to disciplinary traditions. This expansion of disciplinary literacies offers opportunities for youth to engage in knowledge production and critique that affirms and sustains the rich tapestry of knowledge that shapes our worlds. For example, a former student and colleague, Diana Bonilla articulated the need for plant biology units to also incorporate the familial and indigenous use of plants for medicinal and culinary purposes in Latinx communities. To keep those practices obscured from disciplinary knowledge reduces our humanity and reason for understanding disciplinary perspectives. Transdisciplinary inquiry opens portals to a more inclusive and just learning environment.

Provocations for future practice

I hope the metaphors of pathways (multidisciplinary inquiry), prisms (interdisciplinary inquiry), and portals (transdisciplinary inquiry) provide provocations for future practice. Are there spaces in your curriculum that warrant a multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary approach? How might we redesign our inquiry questions to open possibilities for interdisciplinary braiding of knowledge and knowledge-building practices? How might we use this space to share ideas and iterate collectively? To me, this is an inflection point in education that we can see as filled with possibilities for drawing on the passions and inquisitive dispositions of youth to expand learning activities rather than reducing learning to a series of disconnected tasks. Youth deserve opportunities to remake our world and to design social futures in spaces that are lived in and out of school.

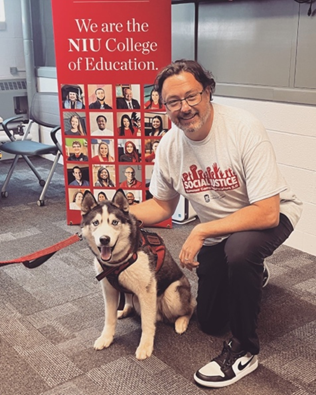

Michael Manderino is an associate professor of literacy education at Northern Illinois University. He taught high school social studies for 14 years and served as a literacy coach, literacy coordinator, and Director of Curriculum of a two-high school district for 5 years.

Follow on Twitter at @mmanderino

Email: mmanderino@niu.edu

Cover Image Photo by Robynne Hu on Unsplash