By: Shanna Towery, South Carolina ELA Teacher

Greeting a classroom full of students and then closing out the rest of the school world with a firmly shut door seems to be the norm for many classroom teachers today. The autonomy afforded to teachers has its benefits, but it can also be detrimental to the mental health of teachers as well as the overall culture of a school.

What’s Wrong with Collaboration?

It would be hard to pinpoint exactly what is to blame for the general ill-will often felt by educators towards collaboration or the dreaded PLC. Maybe it’s the sense of competition garnered from high-stakes testing or the half-hearted attempts at professional development where many teachers are sure to be found half-listening with a stack of ungraded papers. Whatever the cause, the real casualties when collaboration is not fostered, encouraged, and celebrated are the ones who need it the most–our students.

Collaboration: For the Students or For the Students?

Most teachers would agree that students are social creatures. As such, we can utilize their tendencies for communication through class discussion, turn-and-talk strategies, or collaborative groups as effective teaching tools. In this sense, educators are encouraged to use collaboration among students to foster learning in the classroom, but are teachers as willing to collaborate together to ensure every student truly learns? How often do teachers meet in your building to use real classroom data to authentically discuss student progress, successes, needs, for enrichment?

For too many schools, the answer to these inquiries would be disappointing to advocates for professional collaboration. Why is it that collaboration among students in the classroom is a non-negotiable, while the adults in the building do their best to cling to their autonomy? When did we outgrow communication as a means to deepen and build mutual understanding? How can we be so willing to participate in discussion forums, Facebook groups, book clubs, or Bible studies, but hesitate to collaborate with the colleagues in our buildings? And most importantly, what can we do to turn this around?

PLC: More Than Meets the Eye

Professional Learning Communities have gotten a bad rep thanks to half-hearted attempts done simply to check a proverbial box. In reality, PLCs have so much more potential and value when utilized correctly. While book studies and grade level/department level meetings are important and definitely have their place in a positive school climate, the kind of PLCs I have found success with are more about student achievement than they are teacher-centered. In this type of PLC, teachers would meet together prior to teaching to discuss learning goals and objectives. The teachers would not discuss activities or lesson plans so much as they would discuss what they truly wanted their students to gain from upcoming lessons. Only when the goals have been identified would teachers discuss how best to teach for the goals as well as how they would know whether or not the goals had been met (think: assessments). After teaching, the teachers would gather the data from the classroom assessments and meet again to compare notes and discuss patterns, ahas, or concerns. A step often missed here is what to do next–will re-teaching be necessary? Is there room for enrichment? And with true Professional Learning Communities, the cycle would then begin again!

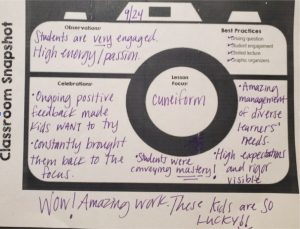

Literacy coaches will recognize what I have described as student-centered coaching cycles (Sweeney, 2011), but as evidenced by a professional development session I was privileged to attend with select members of my district through Solution Tree, this type of PLC has various formats and can take place with or without a literacy coach. Ideally, proper school leadership would encourage this type of student-centered learning approach throughout the building, but all it takes is a few teachers willing to work through a few cycles for it to catch on. As a 6th grade ELA teacher, I was able to conduct a few cycles with a 7th grade social studies teacher last spring before school ended abruptly to offer some insight to her regarding disciplinary literacy. We put our individual expertise together to determine goals for “reading” primary documents and then analyzed data together to inform her teaching. I was able to help her create a rubric for assessment based on our goals and it became very clear through this process what students were understanding and what needed to be re-taught or further scaffolded. It was such a refreshing and rewarding experience to feel that we were collaborating in a way that would truly be useful to both teaching and student learning! Afterwards, I was able to carry the type of work we had done into my grade level ELA planning meetings.

A Call to Action

After years of thinking I knew all there was to know about PLCs and professional development, I found this reimagining of the student-centered PLC to be just the kind of collaboration I could get behind. My hope is that others will see how incredibly beneficial collaboration can be when professionals are willing to meet together on behalf of their students in a non-judgemental or threatening way. Our students deserve it!

Sweeney, D. (2011). Students-centered coaching: A guide for K-8 coaches and principals. Corwin

About the Author

Shanna Towery has sixteen years teaching experience across a total of four school districts in South Carolina. She is a recent M.Ed. graduate from Clemson University and is currently a 6th grade ELA teacher.