By: Kim Ferrari, South Carolina English Teacher

If you were to look through my high school yearbooks, you would quickly notice one thing. Almost everyone was white. I grew up in a very white community in one of the whitest states in America and could probably count on my fingers the number of Black people I knew. As far as I knew, racism didn’t exist any more. The Civil Rights Movement and desegregation brought an end to it and everyone was treated equally now.

I moved to South Carolina in 2014 and learned very quickly that everything I thought I knew about racism and civil rights was wrong.

I watched the news in shock, horror, and disgust as the truth became apparent: racism is very much alive today. This new reality became something that I had to grapple with. I realized that I needed to relearn my nation’s history. For the first time, I began to realize that what is written in our history books is not the absolute truth. There are many untold stories in our history, stories which paint a different picture. As an educator working at a school with predominantly students of color, I knew that I needed to do better and educate myself.

To better understand the new reality and the new culture that I was now surrounded by, I turned to books (as any English teacher would). One of the very first books I read on my journey of truth was The Port Chicago 50 by Steve Sheinkin. I found myself on the verge of tears throughout the book, unable to believe that humans could be so cruel to one another. But then I turned on the news and saw the same types of things happening 60 years later.

Searching Inward

I continued reading books to help me process and understand what was happening around me, focusing on those books written by Black authors about Black youth. The first book that really made a difference was All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. One of the main characters, Rashad, a Black teen falsely accused of stealing a bag of chips from a convenience store, could have been one of my students. This was the first time that I saw not just a character in a book, but a student in my classroom. It caused me to question my personal biases. Did I treat my Black students differently? Was I unfair in my discipline? Did my students all feel valued and seen in my classroom? These were difficult questions to ask myself and I didn’t always like the answers I came up with, but I owed it to my students to ask myself them.

The more books I read by Black authors and about Black teens, the more I learned about the injustices they face. Each book with characters like my students helped me to realize that when one of them calls out “Yo, Miss,” before asking a question, they’re not being smart with me. When a student is more interested in the latest music release or shoe drop than my Shakespeare lesson, it doesn’t mean I’m a bad teacher. These are just some of the things that they grew up with as part of their culture. A culture that I never experienced, but a culture that I can learn about through books.

Making Connections

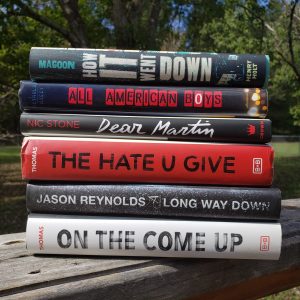

As police violence on Black people continues to happen, young adult novels like The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, Dear Martin by Nic Stone, Ghost by Jason Reynolds, Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds, Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes, and How it Went Down by Kikla Magoon have helped me to see perspectives that I hadn’t before. I saw these events through the eyes of my Black students and while I will never truly understand what it is like to be Black in America, these books offer me a window into their world.

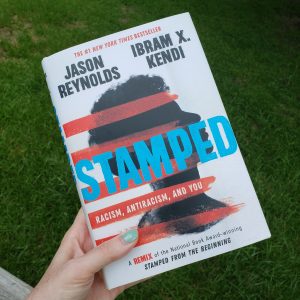

Most importantly, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi taught me everything I never learned in school about slavery, racism, and segregation. What I thought I knew was challenged and I grappled with these new truths. Months later, I’m still questioning much of what I thought I knew about our nation’s history. This new (to me) information has helped me look at current events in a different light and to see how everything that happens today is connected to an event or decision in history.

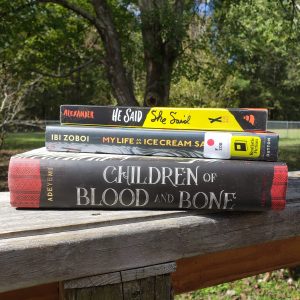

While there have been many books published in the last few years that center on the injustices faced by Black people and while it is important for everyone to read these stories, there is also importance in reading and amplifying stories of Black joy. Instead of focusing on how Black people have suffered, stories of Black joy celebrate being Black, being human, and living life. Books like The Crossover, As Brave as You, My Life as an Ice Cream Sandwich, and Children of Blood and Bone are just a few of the amazing stories of Black joy published in the last few years. With each book that I’ve read, I’ve learned about the importance of music, how different hair styles represent a person’s identity, and how stories are passed down from generation to generation to continue the culture.

Moving Forward

All of these books have helped me to become a better person, educator, friend, and ally. My journey has been difficult at times but it is far from over; I recognize that I still have so much more to learn. Young adult literature will continue to be a powerful resource for me, allowing me to connect with my Black students and to see just some of the ways in which racism still exists in our country.

If you have never read a book that serves as a window into the life of a Black person in America, then I encourage you to read one. If you are White and have never read a book by a Black author, I challenge you to read one now.

About the Author

Kim Ferrari is an English Teacher at Manning High School in Manning, SC. She received her Bachelor of Science in Secondary English Education from the University of Maine at Farmington and is working on her Master’s in Literacy from Clemson University.